The Sassoons and Kadoories created huge, competing business empires, helped open China to the West and aided Jewish refugees in Shanghai during the Shoah – but their fates differed greatly, as revealed in a new book

The chefs were French, the managers Swiss, the jazz musicians American. In the 1930s, the Majestic was Asia’s most luxurious hotel. The world’s high and mighty would stop over in Shanghai just to spend a night there. International celebrities made the gleaming hotel a regular stop on their trips to the region.

But then another hotel – the Cathay – was built in the city, and overnight the Majestic became a second-class place. In the Cathay the carpets were brought in from France, the rugs from Japan, the armchairs from India. Crystal chandeliers adorned the corridors, and a spectacular mosaic ceiling welcomed guests in the lobby. The Cathay was “one of the most luxurious hostelries in the world, rivaling the best in Manhattan,” Fortune magazine gushed in 1935.

The battle between the two luxury hotels embodied the rivalry between their proprietors: two wealthy families that both managed economic empires in Shanghai. They also had something else in common: Their roots were in the Jewish community of Baghdad.

The Sassoon and Kadoorie families were two dynasties, linked by blood ties, who had immigrated to China a century earlier and established flourishing businesses. They owned prestigious buildings and controlled a wide range of industries – from gas and infrastructures to banks, a casino and, in the case of one of them, also the local opium trade. They transformed Shanghai into an international mecca of tourism, commerce and leisure during the interwar period. They changed the face of the city – and of China.

The Sassoons and the Kadoories “played an important role in opening China to the world,” says journalist and writer Jonathan Kaufman, whose newly published book, “The Last Kings of Shanghai,” tells the story of the two families.

“In the 1920s and 1930s,” Kaufman writes, “middle-class and wealthy Chinese flocked to Shanghai, drawn by economic opportunity and a life unavailable anywhere else in China: glamorous department stores, hotels, nightclubs, gambling casinos.” The city the Sassoons and the Kadoories helped to shape “inspired and enabled a generation of Chinese businessmen to be successful capitalists and entrepreneurs.”

Kaufman, a former reporter and editor for the Boston Globe, Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg, and currently director of the Northeastern University School of Journalism, spent six years working on the book, traveling the globe to pore through archives, and speak to relatives, acquaintances and Chinese government officials, to trace the history of the two families.

Ultimately, the fate of each of them was very different. The Sassoons suffered a painful fall, lost most of its fortune in the communist revolution and left China, and abandoned the business world. The Kadoories fled to Hong Kong, rebuilt themselves and emerged stronger than ever in terms of both wealth and influence. The family maintained its status on the mainland over the years, in part by cultivating ties with the communist regime and refraining from criticizing it in public. “Your family has always been a friend to China,” a senior aide to Chinese President Xi Jinping is quoted as telling Michael Kadoorie, the present head of the family.

Amid the multiple revolutions that modern China has experienced, the Kadoories always made a point of treading carefully in order to preserve their standing. As China opened up to the world – in interwar Shanghai, in Hong Kong under British rule and across China, following the establishment of relations with the West in the late 1970s – they flourished, becoming the richest Western family in the country. Their ongoing success is in large measure a barometer of China’s overall receptiveness to the world. Today, with the surge of Chinese nationalism and the deterioration of the political situation in Hong Kong, the family’s future faces a new test.

Ransom to the Turks

The story begins with the Sassoons, an aristocratic family that lived in Baghdad for 800 years and was one of its wealthiest families. Because of its social, political and economic status, which extended well beyond the bounds of the Jewish community, the head of the family was granted the title “Nasi” – a Hebrew honorific meaning “Prince of the Jews” – by the Ottoman Empire.

“In the 18th century, Baghdad was a crossroads of trade, people were coming from all over the Middle East, even from China,” Kaufman tells Haaretz in a recent phone interview from his home, outside Boston. “And all these people would pass through the Sassoons’ house, because they knew they were the most important traders in Baghdad.”

But hundreds of years of economic success and social integration came to an end one morning in 1829. David Sassoon, who was 37 and had been groomed from childhood to inherit leadership of the family empire, was kidnapped and jailed by the Ottoman authorities in Baghdad. They threatened to hang him if the family did not pay a high ransom for his release.

“Desperate for money to boost a collapsing economy, the Turks began harassing and imprisoning the Sassoons and other wealthy Jews, demanding ransom,” Kaufman writes.

The harassment dealt a devastating blow to the family. The Sassoons lost their wealth and influence and decided to leave everything and start anew, elsewhere. David Sassoon believed in the integrity and decency of the British, Kaufman notes, and after his family ransomed him, he decided to move with his wife and eight children to Bombay (today Mumbai), where the British were opening up trade routes. Other Jews followed suit. Sassoon became an Anglophile, studying British history, hiring a tutor to teach his children English and even arranging for the text of “God Save the Queen” to be translated into his native Judeo-Arabic – Arabic written in Hebrew script.

Kaufman: “When David Sassoon had to start over in Bombay and then in China, it was almost Shakespearean. It was not a situation where someone has to start from nothing financially and to move up. It’s someone who has lost their royal power. Someone who was incredibly powerful and influential has lost everything and now wants to reclaim it. Part of what drove the Sassoons was this desire to reclaim what they had once had.”

In India, Sassoon thrived even more than he had in Baghdad. He bought and sold, imported and traded cotton, wool, gold and silver, and exploited his connections and unrivaled commercial experience to become an important bridge between the traditional Middle Eastern world of trade and the global economic system that was developing under the auspices of the British Empire. He was hailed by the British governor of Bombay as “the first of our non-European merchants in wealth and responsibility.”

In the mid-19th century the Sassoons began to conduct business involving another product, one that yielded a particularly high financial return and quickly became their principal source of income: opium. Almost one-third of Bombay’s commerce at the time was bound up with the export of opium from India to China, as well as other countries, Kaufman says, adding that one of every 10 Chinese was addicted to the drug. After David’s death, his son Elias expanded the drug business, and by 1870 the Sassoons controlled no less than 70 percent of the opium exports from India and enjoyed exclusive rights to growing the substance on many of the country’s farms.

“At the time opium was legal in that part of the world,” Kaufman says. “As a businessman, David Sassoon saw the opportunity and began to dabble in the opium trade because it was like dealing in leather goods or cotton. But it became clear that opium was much more profitable.”

However, the situation was not so simple, he continues: “The Sassoons knew how dangerous opium was. No one in the family ever used opium, and in many cases they fired Chinese employees who were addicted to the drug.”

At the same time, there were people in England, especially missionaries but also from other groups, who urged that opium be outlawed. Still, Kaufman says, “it’s clear to me from reading through the papers in their archives that the Sassoons, like British businessmen and rulers, looked upon the Chinese as second-class citizens, so the devastation opium was inflicting on people who were addicted didn’t matter, because they were Chinese.”

In the Sassoons’ case, he sums up, “the moral balance-sheet has to say that they knew they were selling a product that was addictive and caused great damage, but it was legal and they decided to go ahead with it.”

Indeed, the family fought the British authorities’ intention to outlaw opium.

“Under pressure from anti-opium groups, the British government set up a Royal Opium Commission in India in 1893,” Kaufman writes. “Testifying before the commission, representatives of the Sassoons insisted that, if used in moderation, opium was safe. It was ‘a mere entertainment activity for the upper classes,’ one Sassoon executive declared, while another added that ‘if taken moderately opium was very beneficial.’ … Indeed, ‘the Chinese who smoked or imbibed opium were better behaved, quieter, and far more sensible than those addicted to alcoholic drinks,’ the Sassoons declared.”

In their effort to block the outlawing of opium, the Sassoons went all the way to the heir apparent to the British throne, the future King Edward VII (1901-10). Family members went on the prince’s cruises, in various places, entertained him, provided his favorite foods and spent nights at card games and dance parties.

“Most important,” Kaufman continues, “they helped cover his gambling debts,” in part by enabling the prince to acquire opium stock in India and “reaping a profit when it sold in Shanghai.” In fact, “the family made [him] so much money that he joked that he should appoint Reuben Sassoon… as his chancellor of the exchequer, Great Britain’s treasury secretary.”

Reuben, David’s son, was not appointed chancellor of the exchequer, but the Sassoons formally joined the British aristocracy by means of receiving knighthoods and invitations to exclusive events in the presence of the royal family and government leaders. However, it was all to no avail: In 1906, the British Parliament outlawed the sale of opium in China. With this route closed, the Sassoon family’s business turned primarily to hotels and construction of skyscrapers in Shanghai. An exception was their investment in a bank with branches there and in Hong Kong, which would eventually become one of the world’s largest: HSBC.

Chinese kosher

The Sassoons were the first to make the move from Baghdad to Shanghai, Kaufman emphasizes. The moment David Sassoon settled in the city, in the 1840s, he created a local Jewish community from scratch, becoming a one-man immigrant absorption ministry.

Kaufman: “David Sassoon not only sets up schools but he tells the parents back in Baghdad, ‘Send your children to me, your teenagers, I’ll educate them, I’ll make sure they have a synagogue to go to, if they get sick, I have a hospital they can go to, if they die I’ll make sure they get a Jewish burial.’ It’s a good business move.”

Indeed, a steady stream of young Jews were sent by their families in Iraq to work in Sassoon’s enterprises. The Sassoons even brought ritual slaughterers to Shanghai, to teach Chinese butchers koshering techniques so there would be food available for the family’s employees. Indeed, because initially all the Jews who arrived in Shanghai worked for him, the Chinese word for Jewish workers was “Sassoons.”

In addition to creating an organized community for them, employing Jews from Baghdad paid off for the Sassoon family, as it helped them preserve trade secrets in a highly competitive milieu. At the time, the Sassoons wrote in Judeo-Arabic, Kaufman notes – a language that few non-Jews and other Jews in the world knew, akin to a “secret code” with which they could communicate confidentially among themselves and with their employees.

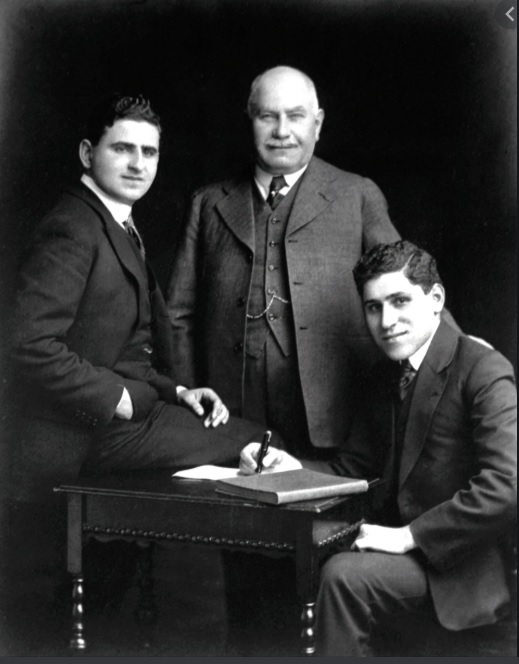

By the late 19th century, the Jewish community in China numbered several hundred people, nearly all of whom had started out in the country in one of Sassoon’s companies. One of those arrivals was Elly Kadoorie, who within a few years would become the Sassoon family’s greatest business rival.

A distant relative of the Sassoons, Kadoorie was 15 when he arrived in Hong Kong from Iraq in 1880. His father had just died, and economic distress prompted his mother to contact the Sassoon family in the hope that they would employ her son. The family took him under its wing and gave him a job as an apprentice clerk in one of its businesses in Hong Kong.

After a few years of acclimatizing and working in minor jobs, Kadoorie decided to strike out on his own. With 500 Hong Kong dollars in hand, which he borrowed from his older brother (who, like him, had been sent to China to work with the Sassoons), he adopted the name E.S. Kelly to conceal his Jewish roots and established a stock brokerage company with two partners.

A significant turning point occurred when he was 32 and married Laura Mocatta, from an established Jewish family in Britain.

“Laura gave Elly [who was living in Hong Kong] entree into the world of London society. They raised their two boys as Britons, from their names – Lawrence and Horace – to their English boarding schools, to the mansion they would buy in London,” Kaufman writes.

In 1901, Kadoorie felt confident enough to change the name of his company to Elly Kadoorie & Sons. It was also then that he made his best investment: in rubber companies in South East Asia. Rubber was much in demand for tires in the then-rapidly growing automobile industry in the United States. From a small trader in stocks he became a successful businessman, from being well-off he rose to millionaire status.

In the 1920s he moved from Hong Kong to Shanghai and built a home for his family that was the largest estate in the city. Known as Marble Hall and designed in the style of the Palace of Versailles, the Kadoorie home had a dining room that could seat 50, parking for the family’s fleet of Rolls Royces and a ballroom the size of a soccer field with a ceiling 25 meters (82 feet) high. Further down the street Kadoorie bought a private house, demolished it and built the resplendent Majestic Hotel. It was “the best, fanciest hotel in Asia,” he crowed – until the Sassoon family’s Cathay eclipsed it.

Says Kaufman, about all these eye-popping construction projects: “The Kadoories had come up from nothing. I think it was their way of announcing their arrival and showing they were influential. They had the biggest mansion in Shanghai, which meant that when Charles Lindbergh flew to Shanghai, they gave a party for him. This was something they probably learned from traveling to England: that a lot of business was done in social settings. The fact that the Kadoories and the Sassoons ran the best hotels and gave the best parties was a way to connect with the elites. When you look at the private papers of the British, what I found out was that they were deeply antisemitic. And how do the Sassoons and the Kadoories cope with that? They could get angry, but instead they decide to give the best parties, the best entertainment, [thinking] we’ll work with people and force them to dine with us and do deals with us. They become the center of social life in Shanghai, it’s a way of expanding their influence.”

With their luxury hotels and glittery soirees, both the Sassoons and the Kadoories made a critical contribution to turning mundane Shanghai into a lively, attractive, colorful city – a kind of cross between New York and Paris, Monte Carlo and London. Kaufman quotes from the diary of Elly’s son Lawrence Kadoorie, written years later: “There never was and never will be another city like Shanghai between the two wars. A city of extreme contrasts, combining the attributes of East and West… Shanghai was a place where one could dance all night, go riding at 6 o’clock in the morning, work all day and yet not feel tired.”

But the Kadoorie family’s investment portfolio contained more than just luxury hotels and prestigious high-rises. Elly Kadoorie was one of the first to identify the vast, latent potential in China, and to a large degree also in Hong Kong, and began to invest in infrastructure there. These encompassed railways, mining companies and above all China Light and Power, which he established together with Chinese investors, Kaufman explains. The company supplied – and continues to supply – power to South China and to a large part of Hong Kong. In Shanghai, Kadoorie did something similar, investing in gas companies, construction firms and transportation. He believed in the city’s potential to grow and rightly decided to invest in its infrastructure.

Recruiting Chaplin

One of the most surprising sections in Kaufman’s book is about the very different attitudes of the heads of the two families toward the then-developing Zionist movement. The approach of each was much influenced by the way he rose to the top.

“The Sassoons came from this almost royal lineage,” says the author, and they immediately connected with the Chinese elite. Throughout Jewish history, he continues, “some Jews look around in different situations and realize they want to be on the side of the imperialists and the colonizers. In England, the Sassoons become friends with the Prince of Wales, they own mansions and castles, they’ve become part of British society. They go on to work for the prime minister, they are friends with Winston Churchill. I think that was the choice the Sassoons made, and it paid off tremendously well for them.”

Judaism apparently did not play a large part in the life of Victor Sassoon, David’s grandson, who ran the family businesses in Shanghai in the interwar period, nor did the fate of the Zionist movement, Kaufman notes.

By contrast, Elly Kadoorie felt as if he were stateless. His applications to receive British citizenship were rejected time after time: Indeed, it wasn’t until almost 50 years after he left Baghdad that he was granted the coveted citizenship, along with a knighthood. “He’s attracted to Zionism the way so many Jews were, in that he was a man without a country,” Kaufman says. “He saw Zionism as a way to protect Jews and give them the security that he personally was missing and that Jews were missing all over the world.”

The Kadoorie family ultimately contributed much to the Zionist enterprise, and even persuaded the Chinese government to support the Balfour Declaration. The Kadoorie Agricultural High School in Lower Galilee was built with funds from the estate of Elly’s brother, Sir Ellis Kadoorie.

Elly Kadoorie’s commitment to his brethren reached a peak in the second half of the 1930s, when ships bearing hundreds of Jewish refugees from Germany began arriving in the harbor of Shanghai – the only city that agreed to accept them at the time. He urged the Jewish communities in the United States and Europe to mobilize and help these refugees, but no assistance was forthcoming. He then turned to his great business rival, Victor Sassoon, to recruit him for the mission.

Kaufman relates that “Elly Kadoorie says to Victor Sassoon, ‘Victor, you have to stop being the playboy, you have to take the lead here, you have to help those refugees. I will follow you, but you have to do this.’”

Sassoon was apparently concerned mainly about what would befall his businesses if Japan invaded China, and no less about the fate of his family in London in case of a German invasion. Nevertheless, he acceded. As befits a “playboy,” he contacted none other than Charlie Chaplin, then the leading actor in the American motion picture industry, and asked him to host a fundraising event in 1937 in the States for the refugees in Shanghai. Chaplin agreed immediately and even donated part of his earnings from his film “The Great Dictator” to the cause.

“Victor Sassoon was a complex person. He was a playboy, he was a millionaire, he was a sharp businessman,” Kaufman says. “He also loved celebrities. He loved being with them, he loved having his pictures taken with them. But during World War II, he really rose to the occasion. And he really did try to use his influence in Hollywood and everywhere else to try to speak out against the Nazis and to find a way to stop the tragedy that was unfolding in Europe.”

The mobilization of the two magnates did not stop at raising funds. “When the Japanese invaded China and joined Germany as an Axis power, the Sassoons and the Kadoories joined forces and achieved one of the miracles of World War II,” Kaufman relates in his book. “As 18,000 European Jews traveled 5,000 miles from Berlin and Vienna and streamed into Shanghai fleeing Nazism, Victor Sassoon negotiated secretly with the Japanese while Nazi representatives urged the Japanese occupiers to pile Jewish refugees onto barges and sink them in the middle of the Huangpu River. Together, the Sassoons and the Kadoories did something that Jews in Europe and Palestine and even the United States couldn’t do: They protected every Jewish refugee who set foot in their city, among them thousands of children.”

Sassoon conducted his negotiations – which Kaufman describes in detail – with a Japanese army officer named Koreshige Inuzuka, a vociferous antisemite and ardent supporter of Hitler who called the Jews “the source of evil thoughts.” But Sassoon, the businessman and celebrity thought to be the wealthiest person in Shanghai, took the mission on personally. He pampered Inuzuka with lavish meals, impressed him with his wealth and invited Japanese army officers to stay at the Cathay Hotel at his expense. At the same time, he discussed the possibilities of economic cooperation and possible investments by the family in Japanese companies. Sassoon got Inuzuka to believe that ensuring the security of the Jews in Shanghai was nothing less than Japan’s national interest.

“Sassoon was a ‘leading figure’ and ‘willing to cooperate,’ Inuzuka reported to Tokyo. ‘The leading class of the Jews in Shanghai has become very pro-Japanese,’” Kaufman writes.

The two conducted intense negotiations for two years, until in August 1939 Japan announced that it would not allow any more Jews to enter Shanghai. However, the 15,000 Jews who had already arrived, and 3,000 more who were en route, were protected. In fact, the Kadoorie and Sassoon families placed them under their care, housed them in their hotels and apartment buildings, and provided hot meals, basic equipment, medical care and clothing. Subsequently, they also helped the newcomers find work and created schools, day camps, music programs and more for their children.

But in the end the money, the status and the ties with the Japanese did not help either the two families or Shanghai’s Jewish community. The Japanese, who in December 1941 declared war on the United States by attacking Pear Harbor, decided to change the rules of the game in Shanghai. They demanded that Sassoon and other leaders of the Jewish community draw up a list of all the Jewish refugees in the city. Soon afterward, Gestapo agents raided Shanghai, put a stop to the activity of the Jewish school and arrested Horace, one of Kadoorie’s two sons. The Japanese went on to capture Hong Kong as well, where they arrested Elly, the family patriarch, along with Victor’s other son, Lawrence.

Because of Elly’s poor health – he was 78 and suffering from prostate cancer – the Japanese agreed to release the members of the family to their home in Shanghai. But their luxurious estate, once a symbol of the immense economic empire of the Kadoorie family, became a Japanese base. The Kadoories thus became prisoners in their own home for almost two years, from 1942 to 1944; Elly died later in 1944.

The liberation of Shanghai at the end of the war meant freedom for the Kadoorie and Sassoon families as well. But this was no more than a temporary situation. The Americans liberated Shanghai but then turned over power to the Chinese Nationalist Party, as Kaufman writes in his book, “The bubble the Kadoories and the Sassoons had lived in since the 1840s disappeared. The Kadoories were part of Shanghai now, and for the first time in more than a hundred years, the Chinese controlled the entire city.” The families fled in the face of this development, as “the Chinese had become ‘very anti-foreign,’ Horace reported worryingly to Lawrence.”

Kaufman sums up: “The Jewish presence that had once shaped and enlivened Shanghai was being erased.”

What brought about the final divergence in the routes taken by the two families was the communist revolution. From the first, the Sassoons had been more successful, richer and more influential than the Kadoories, Kaufman notes, but they did not grasp the size of the threat posed by the communists in China. As a result of the revolution, which culminated in 1948, they lost their whole fortune, which had been invested in Shanghai. Their decline was painful, Kaufman says. Indeed, from being the fifth or sixth richest family in the world in the 1930s, today the Sassoons are no longer part of the business world. One descendant is a teacher, another is an official in the British government, a third became a rabbi. All reside in the United Kingdom.

“The irony is that in the end the Kadoories end up much wealthier than the Sassoons,” Kaufman says. “The Kadoories had moved money to Hong Kong and in fact at one point, when the Sassoons are leaving Shanghai and Hong Kong, people advise them to hold on to their property in Hong Kong, but they don’t. And they sell some if it to the Kadoories, who end up becoming billionaires because of it.

“The Kadoories are slow and steady, they build and build and ultimately surpass the Sassoons. Whereas the Sassoons make all their money early, become one of the richest families in the world in the 1930s, and then lose it. The Kadoories, by being more deliberate and maybe a little less impulsive, end up becoming more successful in the long term. The family’s worth today is estimated at $13 billion; they still control the Hong Kong electric company as well as the Peninsula Hotels chain, which are considered the world’s most luxurious hotels. So you have something of a reversal of fortunes.”

Source: Haarez, July 17,2020

WHAT ABOUT THE TWO OPIUM WARS STARTED BY THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT IN 1839 AND 1858 THAT RESULTED IN THE LEGALIZATION OF OPIUM? DOESN’T SOUND LIKE THE BRITISH WAS AGAINST ANYTHING.