Mohammed Salman Hasan was born in Baghdad in 1928, an Iraqi intellectual who from an early age did not accept the existing social order. Despite the poverty of his family, he worked diligently to improve his condition and equip himself with a modern vision. Although his financial means were meagre that did not stop him from persevering; he started by teaching Arabic to a Jesuit Father at Baghdad College in return for teaching him English. He studied under a lamppost as his parent’s house had no lights. In his maturity, he went to extremes to promote the advancement of Iraq and its people and in the hope of making it a state without parallel in the Arab world.

He obtained a scholarship from the Ministry of Education to study in Britain but found out that his name was removed from the list of candidates and replaced by the name of another student from a prominent family. He considered this to be unjust and went to see the Minister of Education (he was 18 years old) and explained to him his situation. The Minister sympathised with him and promised to investigate and vowed to resign if the scholarship was not awarded to my father. After the investigation, he was granted the scholarship, and travelled to Britain; beginning a long journey of study, of becoming better and preparing for a life of sacrifice in the service of Iraq.

He started his study at Liverpool University. In his first year, he wrote a three-line letter to the Economist. When it was published the professor called him to his office and told him that on the basis of those three lines he would award him the degree. He graduated with honours from Liverpool University in 1952.

He was one of the founders of the Iraqi Student Society in the UK in 1951 and became the Society’s elected president in 1953. Because of his student activity and fighting injustice in Iraq, his scholarship was revoked and passport withdrawn by the Iraqi government. Prime Minister Nouri Saeed asked the British government for his deportation. Penniless and stateless he got a scholarship to do his Masters at the London School of Economics which he finished in 1955. He was then offered a fellowship in St. Anthony’s College at Oxford University, where he did his DPhil in 1958. For the discussion of his thesis, the College brought in Lord Ballof[1] who was known as a conservative thinker hoping that he might fail my father, but instead, after the discussion of his thesis, Lord Ballof stood up and told him “Sir, I take my hat for you.” Again, penniless, Nouri Saeed sent an envoy to meet my father and to ask if he would become Iraq’s representative in the UN (at 27 years old he would have been the youngest ever representative). Being a fighter against injustice and having taken the student movement of Iraqis in Britain to new heights, he decided, after consultation with his wife Ayser Al-Khaffaf, to decline the offer. He proceeded to go to Iraq. Holding the highest academic degrees in the world, yet he was unemployable in Iraq because of his radical views formed at Oxford.

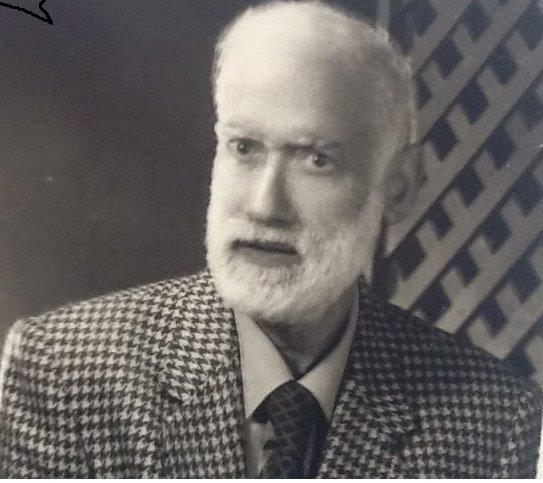

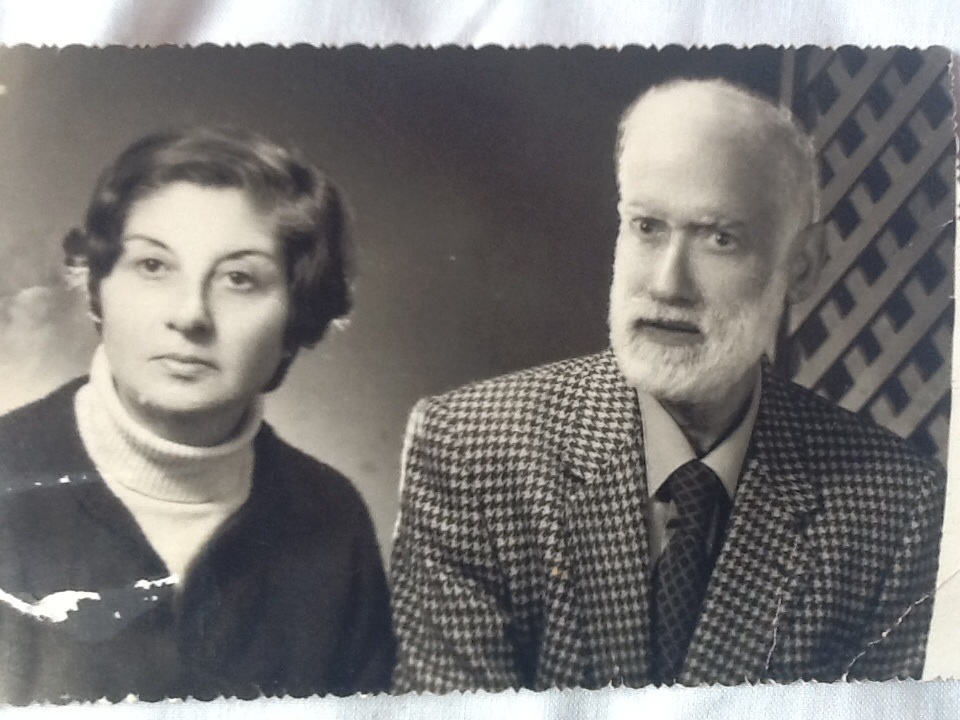

Prof. M. Salman Hasan with his wife Mdm. Ayser Al-Khafaf in 1984

In July 1958, Kassim came to power and asked him to take up a ministerial position but he declined, as he has been away from Iraq for too long. Although he could do the job but felt that he should devote his efforts to do something else, realise justice for the people. He was appointed secretary of Majlis al Eimaar (Development Board). He was now the czar of reconstruction of Iraq.

He was instrumental in the formulation of important laws such as the Agrarian Reform Law and Law No. 80 dispossessing IPC of 99.5% of its concession territory and placing it under the management of the National Oil Company. With that he started a lifelong journey into the unknown working with a very close net of friends.

Just before the coup of February 1963 Kassim asked him to take up the Ministry of Oil or Finance but declined. He has been at odds with Kassim over the way things were developing in terms of turning the government into a dictatorship. Early in February 1963 Kassim issued an order for his arrest, but that order was overtaken by the Baathist coupe of 8th February. He was arrested and sent to the notorious Nugrat el-Salman prison.

My mother was heavily pregnant with my brother Ammar. She was about to give birth in early February 1963. My father, anxious about the evolving political conditions of Iraq, thought that this birth was coming at the wrong time, as Iraq was going to change to the worse while we are busy giving birth. That was typical selfless thinking from him.

This was the time when his lifelong fatal relationship with Saddam started, who tortured this Oxford University Fellow who by then was offered a Chair of Economics at Oxford but declined. He subsequently lost his hearing because of the torture he had undergone. He refused to co-operate with the regime. There were stories about him while he was imprisoned one of which was that he would move his sleeping mat away from people who were singing like canaries to the Baathists betraying the names of opponents of the new Ba’ath regime.

During the period at Majlis al Eimaar he oversaw all public construction contracts for Iraq and as his wife recalled he refused all kinds of gifts and bribes to endorse or to give contracts to certain people as this was against his convictions and social vision. Friends recall that he would have rightly become a billionaire with a stroke of his pen but that was stealing from the people, something that he abhorred and would never contemplate.

During the period 1963-1968 he stayed unemployed and devoted his time to writing books. Despite numerous very generous offers to work abroad he had steadfastly refused to take them up. At that time he was building a new house and was heavily in debt; he relented and took a post in Kuwait for a UN regional development office. He was the first Iraqi to be appointed as a grade “A” consultant in the UN. On arriving Kuwait, being an Arab, he was given substandard accommodation. He told the driver to turn around and take him to the airport to return to Iraq (non-Arabs at lower grades were given much better facilities). So after some discussion he was provided with his just deserve, a luxury flat in Salmia District with a sea front view.

In comes 1968 with the Baath Party back in power. On 30th July, Al Bakr calls the Iraqi Embassy in Kuwait to search for him, to ask him to become prime minister. The embassy staff who had no idea where he was ran around and managed to locate him. Al Bakr spoke with him on the phone. My father said to him that this is a matter that touches the future of Iraq and cannot be discussed over the phone. Al Bakr asked him to hand over the phone to the ambassador and asked the ambassador to arrange for an embassy car to take my father to al Shaibah military base, where Al Bakr will send a military plane to take him to Baghdad for the meeting.

He recalled that while in the plane he wrote a list of 21 demands, which included release of political prisoners, reinstatement of sacked employees, freedom of the press, freedom of political parties, civil & human rights, a proper Iraqi constitution, respect for the rights of Shiites and Kurds among many other demands.

He entered the meeting and presented the demands. Al Bakr was receptive but said they will all be done in the fullness of time. He refused to take up any position. He then proceeded to discuss the Kurdish situation, being a lifelong friend of the Kurds and as Mullah Mustafa Barazani described as an honorary Kurd. He spoke on the Kurdish situation. He told me in later years that “not a single head among the politicians involved in the discussions was raised.” He recalls, “I am a man with no political party umbrella.” Enjoying the audience with the President he spoke his mind on all matters, he then proceeded to tell Al Bakr that he would not go back to Kuwait if he was given a license to publish a daily paper. Al Bakr refused that request. The meeting concluded that day with no concrete results. Saddam was in charge of security but he has not yet started his plots to become deputy president. As my father walked out a member of another party who accepted a ministerial position said to him: “Doctor, we could have been in the same government together.” He remarked that he was not here to seek a position for himself but to set out the rights of the Iraqi people. Saddam was right behind him and commented: “This son of a bitch thinks he has made the revolution.” The mutual hate relationship continued.

He proceeded to go to Kuwait for his position there; he finished his one-year contract and came back to Iraq to take the position of head of the economics department at the University of Baghdad. One of the first things he did was to ratify the syllabus by the London School of Economics.

In 1969 after buying a new car, which he was proud of, he would only have it serviced by the car dealer. The day after the service an assassination attempt was made on his life. The petrol pipe was left loose in the car so that the car explodes on starting the engine. My father, brother and I were in the car, we saw a ball of flame coming from under bonnet. We jumped out of the car before it started to burn.

In contrast, the President of South Yemen invited him to help in the reconstruction of the newly liberated Yemen from Britain. There he started a lifelong love of Yemen and its people. He donated his services to the government and used to travel to Yemen twice a year, as presidential advisor on economic matters. He wrote three 5-year economic plans for South Yemen. In 1971 Salim Rubai Ali,[2] the president, in recognition of his work offered him £1 million as a just reward for services rendered but he refused saying that he was there donating his services in solidarity with the new state and not charging for it. He was much admired by the whole Yemeni government. The president of Yemen not being able to persuade him to take the offer rewarded him symbolically with a Yemeni dagger, thus considering him an honorary Yemeni. The dagger was pre-Islamic with the handle made from rhino horn. He continued his donation of services until 1977.

Upon returning to Iraq, he was interned by the security services and tortured by placing his body in boiling hot water then in ice cold water. This led to his kidneys starting to fail. This was the beginning of a lifelong struggle with illness.

In 1971, while visiting Yemen, we lived in the Garden of Eden, the palace created for the British Council in Yemen. We had a driver and other privileges. We also wined and dined with the political leadership who were, in contrast to Iraqis, very modest and humble and even approachable as they were pure and uncorrupted I suppose.

Also in 1971 with his lifelong friend Mullah Mustafa Barazani, he proceeded to map the opposition to the Baath regime by calling a conference in Gallalah. He was the independent democratic representative in the conference. I remember coming back from the conference by car, he said to me and my brother, that the most valuable thing in his life that God gave him were his eyes, but if the Iraqi people asked him to take Iraqi sand to put it in his eyes to blind him, he would willingly do it as sacrifice to the people. This was the start of a journey of sacrifice for the whole family; I was young and did not understand the context.

In 1973 Saddam consolidated his control of the internal security services and management of Iraq’s oil resources and became the deputy president. In a famous speech asking the Iraqi people to make sacrifices he mentioned that we have professors who work in Kuwait for 800 dinars a month salary, a direct reference to my father. As the government was proceeding with the implementation of Law No. 80, which was set out under Kassim stripping British interest in IPC, my father was excluded from involvement in these developments but he was consulted privately by friends who were tasked with the process. He continued to serve on the board of the Iraqi Central Bank and was given a gold medal for lifelong service there.

He was arrested and interrogated by Nathim Gzar, head of security. In talking to him about economic policy, Gzar replied: “Doctor, some people will face the desert wind and some people will be eating chickens,” in direct reference that if you continue with your opposition campaign you will be dealt with accordingly.

He opposed the National Front that the Communist Party entered with the Baath Party on the ground that the former was not very strong, and as if he realised that this was the start of a dark chapter in the history of Iraq.

Being immaculate in his dress, he wore handmade suits. One day a delegation from the Communist Party came to visit to ask him to join the National Front. The scene was unbelievable; he wore khaki trousers, red shirt and brown jacket. He apologised to the delegation that he had to go on a family picnic to an orchard that day. He promptly took us to Al Taji and asked a farmer there if we can have a picnic on his farm. With customary Arab charm, the farmer agreed, and brought us home-made yoghurt and made tea for us. He sat and chatted with my father. My father felt embarrassed and sensed danger, as we were followed by the regime’s security men, in case the farmer gets into trouble. As it was spring time, he asked the farmer if he had any produce he could buy. The farmer understood the message. He promptly went away and brought two baskets full of oranges and asked for 5 dinars; my father paid him 10 for his permission to use his land and hospitality.

He was very strict and principled and expected the rest to be the same. One day he was building a granny flat for my grandmother (his mother). He was not there to supervise the construction. There were a number of labourers putting a layer of hardcore before concerning the floor and I could see he was vexed as they were on a go-slow mode; they have done very little. On coming back, he looked to check on the progress of the work. You could see his anger. He said nothing but continued all evening in a solitary manner. I went to him and said, “You are upset about what you saw.” He did not answer but I knew what was bothering him, so I thought let me make him happy and be proud of me. I said how much you paid the labourers today. He said 100 dinars; so I said, “Look, there is no need to be upset, I with my brother will finish the hardcore job, you give us 50 dinars.” We shook hands. Being the brains, I told my brother to bring a wheelbarrow and he proceeded to bring broken bricks. I laid them and we finished the job in 3 hours. When he came later and looked at the site, you could not believe his smile and how proud he was; he paid us the 50 dinars. I gave my brother 20 dinars and kept 30 dinars as the ‘main contractor.’ The next day when the labourers came he gave them a lecture that they should work honestly and not rip off people for short term gain. They worked like clockwork from then on as they felt his honesty and power of persuasion.

In 1976 Saddam started his national slogan campaign one of which stated that people who do not work should not eat. A new member of staff joined the economics department after completing his PhD abroad. He was under my father’s wings, who warned him not to discuss these slogans in university classes as security agents are there to record proceedings. One day a student in the class asked the young academic about this slogan, he who does not work shall not eat, to be a discussion point from a pure economic point of view. He said a child eats but does not work, as he will be working in the future; an old man eats and does not work, as he has worked in the past. For that the young academic was fired and persecuted and stripped from his doctorate and sentenced to 20 years hard labour.[3]

This incident was causing lots of discussions and anger among faculty members and students at the university. Then the dean was asked by Saddam about this incident. The dean said that this incident is nothing compared to what Dr Hasan would say; if he says something the whole university will go on strike. Saddam proceed to retire my father at the age of 44 (having been able to work for less than 15 years since 1958). Earlier that year, as part of another campaign that he led for intellectuals in Iraq, following the law passed by the government allowing Iraqis with postgraduate degrees abroad to return to import tax-free cars, personal effects and household goods, and giving them land and loan facilities to build houses. My father started a campaign that existing academics in Iraq with similar higher qualifications should also be given the right to import a car, which was granted. He was 3rd in Iraq in terms of qualifications and he got his beloved Mercedes.

In 1976 he had a daughter, Arwa,[4] named after a Yemeni princess. She died at nine months; it was rumoured that an injection in hospital caused her death. Torture now proceeded on a higher level by personal attacks, and the reign of Saddam’s terror has started in earnest.

While working in Yemen he suffered a total kidney failure, he proceeded to London for treatment. Abdul Fattah Ismail,[5] head of state of South Yemen, offered my mother a bundle of dollar bills rumoured to be over 1 million. My mother said to him have you asked him? Ismael said, “yes but he refused.” So she said, “and what do you expect me to do, take it and hide it; no thank you.”

Salim Rubai Ali, head of state of Yemen, offered him, as an honorary Yemeni, to become Yemen’s representative in the UN. He politely refused and said, “If I ever become a representative it would be of my country of birth.”

I left Iraq in 1977 to study in Britain. My father proceeded to convert our house in al-Dawoodi district to two semi-detached houses, for me and my late brother Ammar so that we are secured for life. He had hoped he could rent them out so there would be some income for the family but these houses stayed empty until the late 1980s. In the meantime, Saddam’s mental torture of my father continued.

I visited Iraq and my family in Iraq for the last time in August 1981. I sat with my father and discussed the conditions of Iraq. He said that Saddam had deceived many people; some have expected that once he got into power that he might change his ways and not start a disaster that we now know ended in the American occupation in 2003. I asked him that he should consider leaving Iraq. He said to me, “Son if I leave like all the others what will the Iraqi people say, even Dr Mohammed left us to face the wrath of this dictator? I will stay and fight and oppose in a peaceful way, like Ghandi.” I personally think this was wrong for two reasons. Firstly, saving the family from slaughter; and secondly, his active opposition abroad could have stirred the people and possibly led to avoiding the disaster that followed in Iraq. This, of course, we will never know.

I went out with my brother walking in the streets of Baghdad and he would tell me how the standard of living of the family dropped. They were eating canned lamb meat imported from China, as they could not afford to buy fresh meat then, a sign of things to come to the whole people of Iraq.

When I was about to leave back to London my father asked me to do something in the aeroplane, on leaving the Iraqi borders, in a gesture of defiance: to stand up in the plane and salute the enduring Iraqi people, which I did. Everybody was looking at me, no questions were asked, no comments were made, they just looked at me in a strange manner.

During the early eighties the first attempt was made to kill my brother. He was driving the family Mercedes. While waiting in al-Shawaf Roundabout in al-Qadissiyah district in Baghdad, an army lorry smashed the car from the back ripping out the boot, spinning and rolling the car right into the roundabout. My brother told me that had he not had the seat belt on he would definitely have died.

Because of the several arrests and torture sessions, my father’s kidney started to get worse, which culminated in the need to have a kidney transplant in 1982. He called me on the day of my final exams (he miscalculated the finishing date of the exams) and said “I want you to go to the exam and make sure you get the best grade possible” which I duly did.

His nephew was sent to the war zone to be executed by death squads in the Iraq Iran war.

One day I found out from his good friend Ali Hadi al-Jabir that he was coming to London with no money to have the operation. He would not plead with Saddam over his illness. Eventually he was persuaded by friends to write to him. He did write a letter addressed simply to the President of Iraq without the mandatory high flown appellations although many people pleaded with him to do so but he refused and remained defiant. Nevertheless, he was given the treatment funding. The whole family was in London. My father and mother stayed in my room, my brother and I slept head and toe on a sofa bed. Tissue matching indicated that my brother, my cousin and I were exact matches. My cousin’s tissue matched my brother’s, but my cousin declined donating a kidney to save his uncle. We were left, me and my brother, to decide on who should donate. I said to my brother, “I finished my studies, I could donate (and be exempt from army service) and go back.” He had just finished his first year as a medical student. He could stay here to recuperate and possibly start university here as a first year student. He said he would lose a year of study, if he donates, but he too could be exempt from military service. I could somehow work abroad and finance his postgraduate studies (little did he know what was to come).

My father sent me one day to go to the Yemeni embassy to talk to the ambassador and deliver a message regarding the cash offered to him, the million pounds promised by Salim Rubai Ali. By then Salim Rubai Ali had died in a suicide bombing attack and Ali Nasir Mohammed[6] took over who was also a friend. But to this day I do not know if Ali Nasir got the message from my father. While still in London, my father refused to take donations offered by fellow Iraqis to buy a house and stay in the UK.

With no money and not willing to live off hand-outs, he asked my brother to return to Iraq, thus sending him to his death, followed by my mother and he was to follow them shortly.

I was living with him in a studio in Hampstead, where he met Iraqi opposition figures from the far left to the far right, Islamic and Kurdish, who all pleaded with him to stay and lead the opposition to Saddam. I remember his words, “you set up a united front; stop belittling each other’s (parties).. I am going back to Iraq to fight the good fight, once you have done that I will be happy to come and lead and not before.”

As if he knew this would be the last time we will be together, we did things together and he had time for us to go out and instil in me what he wanted to be done. We used to go for walks and discuss all sorts of subjects, religion, life, philosophy and politics. He took me to where he used to live in Hampstead, looking and remembering old friends he made. One day he was looking for a book which was out of print. We found a small bookshop in Primrose Hill so we went in. The shop owner said it is unlikely that he has the book but suggested that we look in the second-hand section downstairs. My father passed by an English gentleman; the space was tight so both had to squeeze to pass each other, and then the Englishman looked at him and said “Hasan, my God!” They have not met for almost 20 years. They were kissing and hugging. The man was his long lost friend.

His passion was literature. I think that he had one of the largest private libraries in Iraq, approximately 30,000 books. He read a book every 1-2 days. One day he said out of the blue, “my son, try not to associate with Iraqis a lot, try to live and learn from England and its people; they have culture but this does not mean forgetting that you are an Arab but take the good things from the English like the value of time and the purpose of living and bettering yourself. This would be needed after you make your journey home; the soldier is fighting in the front, you have a duty to your country to learn and attain, seek as much knowledge as possible, sit down, think, analyse, discuss with yourself, sure you will make mistakes, learn from them, but make sure and consider this is your war, make progress; you will be needed to go back to continue the journey of your family; make sure that the injustice being done to the Iraqi people is righted and this is not going be done by an outside force. It is you and the collective efforts of the Iraqi people who are going to produce the results.” These were his words in 1983, 20 years ago, while departing on a flight to Austria. I did not know why he chose to go that route. Recently, I found out that he went to say goodbye to his brother as he knew he will be persecuted and tortured and killed in Iraq, a martyr for the freedom of the his beloved Iraqi people. He also said, “I will step with my shoes on all my qualifications if this benefited the Iraqi people.” He left, not to be seen again except in the hearts and minds of the people of Iraq.

Ammar had a passion for cars. One day, as he was making things, he made a bumper design for the Mercedes car. When the Mercedes engineers came to Iraq and saw his design, they asked him to sign an agreement on handing over of a patent on the design. One day, he came to my father, after visiting a car market, and said that the latest Malibu Chevrolet has just arrived. My father said to him, “one day you people are going to beg for camels.” How true this statement was. In a typical visionary manner, he read the future.

In 1983, Saddam’s half-brother Barazan attempted a coup to end the war with Iran. In private discussions between the conspirators they agreed that they needed an independent clean person to lead Iraq and decided that my father, without his knowledge, was the one. Of course, as with everything in the state of terror, this discussion was recorded and brought to the attention of Saddam. The coup failed. Barazan was sent to exile in Switzerland. In contrast, my father was arrested and taken to al-Shamaiya Mental Hospital. Every night, as my mum told me, the management of the hospital released the psychopaths on him to beat him. He would resort to find hiding places under the beds in a corner to avoid them. He told my mother that the most heartfelt thing was bringing one of his former students to torture and beat him up. He was exposed to mental torture by bringing a woman when he was blindfolded and telling him that she was my mother and they were going to rape her. They did try to do that but an honest security agent stopped it; that man was later executed during the Iran Iraq war. My father was sent for mock executions more than five times by firing around him. They had intimate details, as they knew things that could only be acquired by camera surveillance inside our house, my mother told me.

In the thicket of his ordeal, he decided to go on a hunger strike that lasted 23 days. The orderlies at the hospital repeatedly tried to force feed him but he would rip off the feed tube. Then it was announced in Syria that he died in prison. People hearing that and in a unique gesture of solidarity marched in Kadhimiya and Adhamiya districts of Baghdad shouting “Mohammed Ghandi of Iraq.” Saddam realised he could not let this go on. He contacted my mother to come and collect him, which she did. The orderlies had to carry him out to her as he could not walk, with a beard down to his chest, flea ridden, and weak. They brought a pint of milk for him to drink. At that moment, thinking that the milk might have been spiked by a lethal drug, decided not drink it realising that this was one way of covering up his murder. Before leaving the hospital, he asked for pen and paper. He wrote a note to my mother. She could only read the heading which read “Saddam an American Israeli Agent” and wrote a full page and signed it. His jailers begged him not to do it as it would be his death warrant. He said, “Fine, execute me.” He knew he won this battle but the war was not over.

When the security men came to take him away from his home they went through the books in his library. They complained on the walkie-talkie to their superiors that there are so many books it would take them forever to go through them. They proceeded to take only books they did not like; my father objected and told them to take the Baathist books as well. He asked them to list all the books. They took away his Yemeni dagger and book manuscripts: A Third Pillar of Economic Theory and Social and Economic Development of the Third World[7] and a project dear to his heart on which he spent years, the draft of a Permanent Constitution. These manuscripts disappeared forever. The dagger, I am told, reappeared with a technician from Fox News as it was taken from Uday’s palace.

Saddam realised that he could not kill him. The only thing open for Saddam was mental torture. This is where the story of my brother Ammar starts. He kept away from politics, seeing the mental suffering of our father. He was a brilliant engineer but decided to become a doctor to help people. He wanted to be a plastic or brain surgeon. He got a place in Basra University to study medicine. During the first year and seeing the magnitude of casualties sustained in the Iraq Iran war, he involved himself in the hospital and started as a cleaner in operating theatres. The foreign surgeons employed to operate on war casualties realising that he was a medical student got him involved in patching operations, etc.. They realised his raw talent. He recalled to my mum that in his first job stitching a soldier, he was going too deep and the soldier would just bite his lips and not scream. My brother apologised to him and told him he was very sorry for the pain he caused and he will attempt to do better next time with others. He used to come back home every day with his clothes smeared with blood from the causalities of war. He became a permanent feature of the hospital and started in his second year doing brain surgery with the consultants, cleaning afterwards and arranging bodies in the morgue.

When Fao was liberated he immediately called all his friends in the medical faculty to come and help. They told him that they have no official instructions. He said to them there is no need, let us go. They drove ambulances and brought casualties to the hospital. He was with the surgeons performing major operations by then. He became a brilliant surgeon and the consultants would call on him to do all sorts of operations even though he was a 3rd year medical student.

One day while he was cleaning the Minister of Health came from Baghdad to commend the hospital; my brother did not know who this man was trying to come into the operations room. While he was cleaning and sorting the morgue, my brother told him off for coming into the area he had just cleaned. The Minister asked the people who were accompanying him who was this young man. They told him that he is a brilliant student volunteer who performs brain surgery and then sorts the operating theatre and the morgue, condoles the relatives of the dead and sympathises with the patients and that he provides his services with no pay at all, yet manages to be the top student of the year. For that the minister ordered that he is given brand new trainers. The minister invited him to come and see him at the hospital director’s office. The Minister told him that for his efforts he is going to make sure he receives the decoration of Wisam al Rafidain of the First Degree.

My father’s ex driver at Majlis al Eimaar (the Development Board) worked between Basra and Kuwait and in a chance meeting with my brother asked him if he was the son of Dr Mohammed Salman Hasan and he said yes. He told a story about my father when he used to pick him up in his government car, registration number 3 Eimaar, to drive him to work. My father lived in a house allocated to him by Kassim. The street was muddy. After shaving and having his shower and dressing to go to the Majlis, he tells my mother to get in the car, “I drive you to the bus stop.” As though he does not know, she says to him, “my office is next to yours” but he says this car is provided for him not for the family; this privilege should not be abused. He will go past my mum waiting for the bus to take her to work.

Here is another story to do with the bungalows that were used by the British before 1958. Kassim, realising that my father had no money or a place to stay, gave him a bungalow. Many people like him who were offered the same privilege lived there but without paying rent, my father insisted to pay rent although it was low, and got receipts for it. When the Baathists came to power, they searched with fine-tooth comb but could not find the trace of any privilege that he has abused unlike the Awjah family[8] who had nothing but left power as one of the richest families on earth. What a contrast!

The most gruesome task was sorting body parts of the soldiers blown apart, my brother said. When the Baath Party representative came to him, jealous of his hard work and achievements at college and hospital, told him, “I am going to recommend you to the party for commendation.” He said he did not want that or anything else, he just had one question: why she and other party members did not volunteer for the war effort? She said “I have exams and need to time to study.” He said to her “so did I and others, we do operations and study in our spare time.” This conversation was reported to the security department. He was interrogated by Hamza al Zubaidie.

Once he was told that our father was against the revolution. His reply was that he was proud of his father. They told him we will show you. Two weeks later while eating outside Katkout takeaway in Basra an army car careered onto the pavement, threw him to the air and landed him on his head on the bonnet of the car. The driver ran away. He was in hospital fighting for his life, the resident doctor injected him with a drug to make sure he stops fighting and causes his death. When he died, the consultants and medical lecturers were crying outside his room saying that they expected a lot from him as a brilliant surgeon in the future. All were aware of what happened but could not do anything or say much more.

My mother, grief stricken, asked for fresh dates to be brought to the hospital and distributed to his beloved soldier patients in the hospital. The soldiers have by now heard the story of my brother’s death. All she said to them, distributing the dates, was to remember Ammar. They asked, “Was he the blonde surgeon who operated on us.” That was enough evidence to confirm the story of my brother.

As my mother was watched all the time by security agents, people who knew the family could not say anything, they used my auntie as go between. They told her to claim for compensation from the Iraq Life Insurance Company. My mother being an employee of the Iraq Reinsurance Company, had free life cover arranged by the latter for her and members of her family. This was the only way to get my brother’s murderer to court. The murderer was under instructions emanating all the way from Saddam & Uday to perform the deed. In a private party one of the Baath leaders admitted that they wanted to teach him a lesson but murdering him showed how cheap was human life for them.

Proceeding with the insurance claim, the insurance company had to get the murderer and prosecute him. However, no solicitor in Basra would act on our behalf, so my mother, accompanied with my auntie, went to court on their own. My mother fully expecting to be killed went and started prosecuting her case. In the courtroom she said to the murderer, “you do not need to see a picture of Ammar as you already knew him,” but showed the picture to the people present in the court. The court was crowded and as more people heard about the case they come in large numbers and stood in the court. The security agents realising the explosive situation posted armed guards outside the courthouse. My mother proceeded with the prosecution, she said to the judges that the driver should be executed for the fact the he left Ammar dying on the roadside and ran away, never mind the murderous act itself. The court sentenced him for two years in prison but the sentence was not served. My mother told my brother’s murderer she will wait to see him end in hell. The murderer used to send messengers to my mum asking to come and kiss her foot and beg for forgiveness. Apparently he lost his mind afterwards. I have all his details as well as the doctors who colluded in the death of my brother at the hospital. I intend to get justice done when I go back to Iraq.

Going back to my father. This did not work (the murdering of my brother). He became a recluse, sleeping on the floor of his library, instead of being dressed in suit, he started growing a beard and wearing dishdasha, going every morning to a nearby shop to buy milk and the Iraqi Official Gazette, devoting his time to reading and writing.

On his death, his library was opened. In retrospect, it seems that my father wrote his own obituary. He received telexes offering him professorship at Oxford, Cambridge, Princeton, Harvard and Yale universities, as well as from the head of the UN Development Office in Japan with diplomatic passports for the whole family and a $1 million yearly salary, all of which he telegraphed back with apologies.

The Baathists not being able to finish him off offered my mother that he be exiled and that they will give him a house and a salary anywhere in world just so that he is out of the way. My mother said to them that she has told him about this offer, but he refused. The Baathist emissaries asked her to sign the offer and it will be implemented. She promptly refused.

My parent’s house was riddled with bullets from silencer guns. The windows had bullet holes and that was the reason why my father slept on the floor of the study because it was the safest place in the house.

He ironically died on 17th January 1989 the same day on which the bombing of Baghdad in Second Gulf War started in 1991.

In February 1990 my mother came to England to tell the story of our family, which was by and large unnoticed. I remember her in black since my brother’s death. She vowed to wear a red dress on Saddam’s downfall but she did not saw that day as she died a broken woman on 16th July 2002.

On 9th April 2003 when Saddam fell, I thought of taking a red dress to her grave, then thought I do not think this would be the way she would have thought of Iraq under occupation. She would still be sad because the almighty Iraq is under direct rule by the USA and the suffering of the Iraqi people continues. The only light in her life was the next generation that might bring a better life for Iraq through their actions. So I continue to teach my daughter on the family sacrifices hoping she can deliver what we all might have failed to give – democracy and decent living to the Iraqi people.

The irony in this family never ends. The 1st anniversary of my mother’s death falls on 14th of July, the date of the 1958 Revolution. I hope to go back to Iraq soon to visit, for the first time, the graves of my martyred father and brother in a sad broken Iraq, to seek justice and compensation for our family’s suffering.

Many people have commented that this story should be turned into a Hollywood-style film about family suffering in Iraq.

London 2003-2004

* Mr. Yasar Hasan is the son of the late Prof. Dr. Mohammad Salman Hasan. He wrote the manuscript during the years 2003-2004 in London. The manuscript has been thoroughly reviewed and edited in September 2014 by Mr. Misbah Kamal.

Copyright: Iraqi Economists Network.

Please contact info@iraqieconnomists.net in order to get permission for republishing.

[1] I heard this from my mother and I am not sure of the correct name. The external examiner might have been the historian Max Bellof (1913-1999) or the political economist Thomas Balogh (1905-1985).

[2] Salim Rubai Ali, 1935-1978. (Editor).

[3] The academic was Dr Talib Al-Baghdadi who would years later record his experience in a book My Story with Saddam (Dar Al-Warraq Publishing, 2010) (Footnote by the Editor).

[4] Arwa Al-Sulayhi, 1048-1138. (Editor).

[5] Abdul Fattah Ismael, 1939-1986. (Editor).

[6] Ali Nasir Mohammed, 1939-. (Editor).

[7] I am not sure of the exact titles of these manuscripts as I am recalling them from past conversations with my late mother.

[8] Saddam Hussain’s family. (Editor).

Comment here