It is a narrative we are all familiar with, since it has been repeated by scholars, journalists, and political commentators of all stripes for close to a century now. I have repeated it myself on a number of occasions.

The “artificial state” narrative was also invoked by the Islamic State (IS)—formerly known as ISIS—when the group released a video called “The End of Sykes-Picot” in the summer of 2014. It proclaimed that the dissolution of the Syria-Iraq border spelled the end of the nation-state system imposed on the region by the colonial powers after World War I, and promised that “This is not the first border we will break.” Speaking from a mosque in Mosul in July, the group’s leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi explained: “This blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes–Picot conspiracy.”

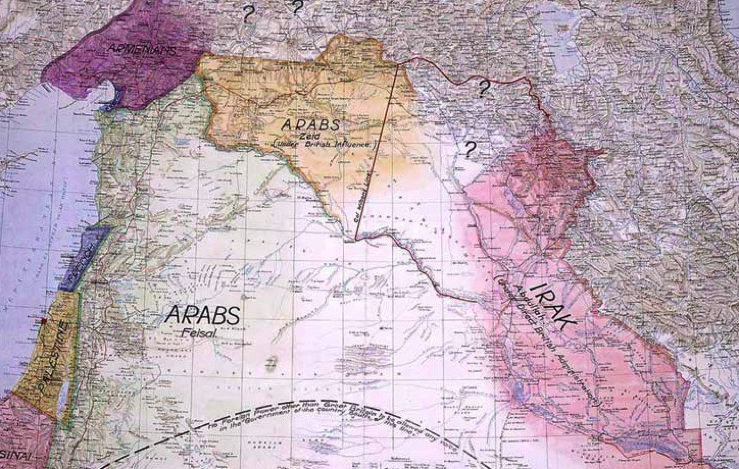

A flurry of media commentary ensued, and Sykes-Picot maps popped up across the Internet as supporting evidence, or at least supporting decoration, for a range of opinions on the IS pronouncement. The dominant response, even among staunch opponents of IS, seemed to be that the group was indeed undoing the infamous 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement between Britain and France divvying up the Arab lands of the Ottoman Empire, and that this was the logical demise of artificial borders created by the colonial powers a hundred years ago. A Reuters article, entitled “Sykes-Picot Drew Lines in the Middle East’s Sand that Blood is Washing Away,” explained that the agreement had been “an inherently imperial project, which paid scant regard to geography, terrain or ethnicity.” Public intellectuals from the far right to the far left agreed; even before the IS advance, Noam Chomsky was quoted as saying that “the Sykes-Picot agreement is falling apart, which is an interesting phenomenon . . . But, the Sykes-Picot agreement was just an imperial imposition that has no legitimacy; there is no reason for any of these borders—except the interests of the imperial powers.” There were a few dissenting opinions, most of which questioned whether the Iraq-Syria border was really dissolving. For example, Steven Simon wrote in the August issue of Foreign Affairs: “Thus far, the parade of horrors emanating from Syria has not included the demise of the Sykes-Picot borders . . . In short, despite the regional pandemonium, Sykes-Picot seems to be alive and well.”

More rare were critiques of the Sykes-Picot narrative itself or the broader artificial state narrative of which it is one strand. There were some notable exceptions, including a brilliant piece by Daniel Neep arguing that the fascination of pundits everywhere with how a better map of the region might be created is “no more than a fantasy concocted from a phantasm, an illusion distilled from the fragments of a half-remembered dream.”[2] But for the most part, the fragments of the half-remembered dream held sway. Indeed, few even bothered questioning the claim that the border IS was challenging had in fact been created by the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement. This near-consensus was striking not only because more accurate information was available for anyone who chose to search for it, but also because it was available right at the top of most of the commentaries themselves, in the form of the Sykes-Picot maps soberly displayed above article after article, as if those images actually served to illustrate the claims at hand. That the Sykes-Picot map does not look very much like the present-day map of the region rarely seemed to warrant explanation. In fact, it can be argued fairly easily that the boundaries of the region IS currently controls look more like Sykes-Picot than does the internationally recognized border between Iraq and Syria. I will return to this point.

What I am interested in, as a historian of Iraq, is not just what might constitute a more accurate historical narrative of Iraq’s formation—though that will be part of what follows—but also how we might think about this peculiar disconnect between the images provided and the story being told about them. It suggests that the artificial state narrative may never be very troubled by historians duly correcting the historical record. Rather, the narrative itself may need more rigorous examination. Where does it come from, what is its history, and how does it relate to the history of colonialism, nationalism, war, and occupation in Iraq over the past century? What kind of work has this narrative done historically, and what does it do today?

The discourse of Iraq as an artificial state—an irrational amalgam of heterogeneous peoples—emerged in the 1920s, as I will show in Part 2 of this article. It was originally a colonial narrative, invoked to argue that Iraq was not yet coherent enough to govern itself, contrary to the claims of Iraqi nationalists, and that it must therefore be governed by Britain. That it later also became a nationalist narrative—especially an Arab nationalist narrative—may help to explain its persistence. In the wake of the US invasions of 1991 and 2003, it was dusted off and trotted out in particularly virulent ways by the pro-war camp and their later apologists. After all, what harm had been done in destroying a country that had never authentically existed in the first place?

Jeffrey Goldberg, for example, made this argument in a widely quoted 2008 article in The Atlantic, titled “After Iraq.” The cover of the issue displayed the predictable ethnosectarian fantasy of a remapped Middle East (see the above image). In a follow-up piece published during the IS advance last summer, subtitled “Why should we fight the inevitable breakup of Iraq?,” Goldberg professed sympathy for the Sykes-Picot map, but asserted that its weakness had been that it was too “progressive” for the Middle East, which

just “isn’t the sort of place” where “modern, multicultural, and multi-confessional states” can be established. These arguments are suggestive of how the recent proliferation of Sykes-Picot maps might bear some relation not only to the advance of IS but also to a revived sense of imperial power at this particular juncture. That is, we might read the maps less as historical explanations than as invitations, imagination-sparking supplements to the equally rapid proliferation of proposed re-mappings.

The Sykes-Picot Map

[Sykes-Picot Agreement Map signed by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, 8 May 1916. Image from UK National Archives MPK1/426, FO 371/2777 (folio 398). Image from Wikipedia.]

As historical explanation, the Sykes-Picot map does have some flaws. There are numerous versions of it, some considerably more misleading than others, especially with their creative use of colors and patterns to make the thing look as much as possible like the current map of the region. Nevertheless, the original 1916 version, signed by Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, is commonly used today (see the above image). The red-shaded area in the lower right of the map was to be under direct British rule. I will call this

red area “Iraq,” since that is what it was called at the time, by Arabic and Turkish speakers as well as by some European officials and geographers. It included most of the Ottoman provinces of Basra and Baghdad but not the Ottoman province of Mosul or the desert region now called Anbar in western Iraq. In Sykes-Picot, it also included a significant area not in present-day Iraq, a long slice of the eastern Arabian Peninsula encompassing present-day Kuwait and the coast of present-day Saudi Arabia down to Qatar (not fully displayed on the 1916 map).

The area under direct French control in the Sykes-Picot plan, displayed in solid blue shading, consisted of a large part of southern Anatolia in present-day Turkey plus the Mediterranean coast down to Palestine. Nobody knows what to call this entity, since it is hard to match up with the map of any state today or any notion of a geographical region in 1916. The simplest solution, and the one adopted by most commentaries on Sykes-Picot, is to ignore it.

The central area of the map, the “A” and “B” territories, was to be an “independent Arab state” or “confederation of Arab states,”

the northern (“A”) region envisioned as a French “sphere of influence” and the southern (“B”) region as a British “sphere of influence.” This aspect of Sykes-Picot has been much debated, and was intended to be ambiguous at the time, or at least to be left open to future discussion. The public British stance was that the A and B territories were meant to be a single “independent” Arab state, which is how Britain claimed that Sykes-Picot did not contradict the Husayn-McMahon correspondence. But the agreement left open the possibility that they could be two independent Arab states. As for the meaning of French and British “influence,” this was also left famously vague, but it included, at least, economic concessions for each European state within its respective sphere.

The only border of present-day Iraq (see the map above) that can possibly be called a Sykes-Picot line is the southern-most section of its border with Syria, traversing the desert region from Jordan up to the Euphrates river near al-Qa`im—though, as we have seen, this was not the border of Iraq in Sykes-Picot but the boundary between the A and B regions of the “independent Arab state.” Moreover, as I will explain in Part 2 of this article, this border was not actually established by the Sykes-Picot Agreement, in spite of the

correspondence; in fact, the actions of local nationalists had a lot to do with it. The remaining, longer, section of the Iraq-Syria border, from al-Qa`im to Turkey, does not exist in any form in Sykes-Picot.

In important ways, then, the area currently under IS control looks more like the Sykes-Picot vision than does the map of Iraq and Syria. The most important, of course, is the IS conquest of the city of Mosul and the surrounding region, the most densely populated area under the group’s control. This is true regardless of how one understands the A and B territories of Sykes-Picot, since the agreement did not place Mosul within either Iraq or the “B” zone of British influence. It unambiguously placed it inside the French- influenced “A” territory, joining it with present-day northern Syria, much as IS claims it has done. At the time the group released its “End of Sykes-Picot” video last summer, it had also asserted control over a swath of present-day Iraq that was to be included in the “B” territory of the Arab state, much of it desert, though only a tiny part of Sykes-Picot Iraq, as can be seen in both the more and less expansive versions of the IS map.

Over the years, scholars have been less likely than journalists and political commentators to make patently false Sykes-Picot assertions. Some say that Iraq’s borders were created not by the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 but at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. Or maybe it was the San Remo Agreement of 1920. Or it could have been the Cairo Conference of 1921. Or there is always that London civil servant in 1922. But most of these accounts end up in the same place, i.e., that Iraq’s borders were “drawn” by Europeans sometime in the years around World War I. Reeva Simon writes:

An obvious example of an artificially created state, Iraq came into existence at the end of World War I at the behest of the British . . . They drew the new lines at the conference in Cairo in 1921 that created the country of Iraq out of the former Ottoman provinces of Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul.[3]

It is of course true that, as the years go by, the lines being drawn by Europeans—and by everyone else—do tend to get closer to the borders of present-day Iraq. But there is no originary moment in which Iraq’s borders were “drawn”; if there had been, we probably would not need all these competing narratives in the first place. As it is, we can always imagine that there is some map, somewhere, that says what we are all saying it says.

A likely reason the Sykes-Picot narrative continues to be more popular than these others, despite its obvious visual drawbacks, is that it assigns the most agency to Europeans in the process of Iraqi nation-formation. The San Remo and Cairo conferences were both, in critical ways, responses of the colonial powers to changes on the ground, and in particular to demands for Syrian and Iraqi independence, expressed in popular uprisings and armed insurgencies across wide swaths of both territories in 1919 and 1920. In fact, one very interesting way the Sykes-Picot narrative has worked, and which helps to erase the local interventions that shaped the later maps, is that all of these later maps are sometimes called “amendments” to Sykes-Picot,[4] as if one can just keep amending a secret

agreement that was never legally binding in the first place, even in Europe, let alone in the Middle East. So by this rather circular logic, every new map of Iraq is said to be an amendment of Sykes-Picot, and then we can keep saying that Sykes-Picot established Iraq’s map.

A Possible Objection

To anticipate a possible objection: many proponents of the artificial state narrative might readily concede that there was no originary moment, and that Sykes-Picot in particular looks very little like the current map of Iraq. But they might respond that this is missing the point. The point, they might argue, is that Europeans drew the borders, and they drew them arbitrarily—that is to say, on an “empty map”—without consulting the local population and without regard for any other existing reality in the region.[5] If the map was empty, and the borders arbitrary, then who cares where they ended up?

I have two responses. First, the actual location of Iraq’s current borders sometimes matters quite a bit to the perpetuation of the artificial state narrative, and the narrative can’t have it both ways. For example, “Iraq” is very often defined by its current borders precisely in order to erase Iraq of any earlier history, thus resetting the clock to begin with the arrival of European empire. Here is an example of this familiar argument, from a widely used textbook on the history of the modern Middle East by Malcolm Yapp:

It is even more anachronistic to write of the history of Iraq in the nineteenth century than to write of that of Syria. Although the term “Iraq” was an old one, it did not correspond to the area of the modern state and was not used to designate any of the Ottoman administrative districts of the area.[6]

So now we know two things the term “Iraq” did not mean before World War I, but we still know nothing about what it did mean, let alone about the ways in which it may or may not have shaped the later history of Iraq. How was the term “Iraq” understood, we might wonder, and how did this understanding change, territorially or otherwise, from the Ottoman period to the era in which Iraq became a modern state? Why would it be anachronistic to speak of something in the nineteenth century that, as Yapp himself tells us, was spoken of in the nineteenth century? And what does it mean to say that that thing, whatever it was, did not correspond to the area of the modern state? After all, what historians are usually interested in is how things change from time A to time B. Usually we do not simply dismiss historical change as some kind of normative failure of something to stay the same.

The above image, an Ottoman map from 1893, shows the three administrative provinces of Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul. Stretching across the first two of these is the label al-`Iraq al-`Arabi (Arab Iraq). So Yapp is correct that nineteenth-century Ottomans did not use the term “Iraq” to designate any one of their administrative districts; rather, they used it to designate a geographical region extending at least roughly across two of those districts. This is the same region, we might recall, that we identified as Iraq on the Sykes-Picot map. Indeed, the earliest Sykes-Picot boundaries were drawn on English versions of the Ottoman map, displaying many of the geographical labels not even as English translations but rather as direct transliterations of the Ottoman terms. The image below, for example, shows a detail of the original 1916 Sykes-Picot map (the full version of which is displayed earlier in this article), with the transliterated label “Irak Arabi.” There was a good reason for this, namely that at the time of the Sykes-Picot correspondence in 1916, British troops had already occupied Basra and were battling the Ottoman army for control of Baghdad. As they conquered each region, the occupation forces retained much of the Ottoman bureaucratic structure—including many of its administrative borders and geographical nomenclature—for the purpose of governing and taxing the people of the occupied territories.

As far as Iraq is concerned, then, the Sykes-Picot map was derived directly from the Ottoman map, even though the Iraq on neither of those maps corresponds to various Iraqs on later maps, nor is the Iraq on either map designated as an independent state. So why is it, it seems fair to ask, that a non-correspondence of borders from one time period to the next is sufficient reason for cutting off Ottoman Iraq from the later history of Iraq, while the very same non-correspondence is not a sufficient reason to cut off Sykes-Picot from that history?[7]

My second response to the imagined objection—that if Europeans drew arbitrary borders on an empty map, then it does not really matter where those borders ended up on the ground, so that Sykes-Picot works as well as San Remo works as well as the Cairo Conference to make the point—is that we need to look more carefully at this whole concept of an “empty map.” Timothy Mitchell has argued that a central logic of Western modernity is the production of an absolute distinction between reality and representation, “the thing and its philosophy,” the place and its map. The plan, the design, the map all seek to “make everything into a mere representation of something more real beyond itself, something original outside…The real outside was never quite reached. It was only ever represented.” The distinction between representation and reality is thus “the method by which our effect of an original ‘reality’ is achieved.”[8]

The logic of the artificial state narrative depends, I think, on this radical distinction between maps and the real world. The narrative criticizes the maps, but leaves the real world out there—rather murky perhaps, but whole and unto itself, chugging along in some non- map-affected time of its own. On the one hand, the narrative does attribute real historical agency to the European act of line drawing, which, it is certainly implied, really did transform the region by “fabricating” its modern states. On the other hand, the problem with

this process, the narrative also implies, was that the maps were “empty,” that is, they had no relation to the underlying reality of the region in question. This being the case, it follows that there could be better and truer lines, existing somewhere in that non-empty and cordoned-off reality, perhaps yet to be discovered but in any case somehow more real than the lines on the maps we actually have.

Ethnosectarian Visions

This belief in the unchanging existence of better and truer lines may help explain the excitement around the “discovery” in 2005 of a “long-lost” map, shown below, that was drawn by T.E. Lawrence (as in Lawrence of Arabia) in 1918. A widely quoted Lawrence biographer proclaimed that the map “could have saved the world a lot of time, trouble and treasure,” providing the region “with a far better starting point than the crude imperial carve-up” of Sykes and Picot. NPR further explained: “For historians, Lawrence’s map is an exercise in what ifs: He included a separate state for the Kurds, similar to that demanded by Iraq’s Kurds today. Lawrence groups together the people in present-day Syria, Jordan and parts of Saudi Arabia into another state based on tribal patterns and commercial routes.” BBC agreed that Lawrence’s map indicated “separate governments” for the “predominantly Kurdish and Arab areas in what is now Iraq . . . But Lawrence’s suggestions came across opposition by the British administration in Mesopotamia.”

[Lawrence Map, 1918. Image from “Lawrence of Arabia, The Life, The Legend,” Imperial War Museum, London, 2005/UK National Archives, via BBC]

The first point about these responses to Lawrence’s map is, again, the remarkable lack of correspondence between the image provided and the claims being made about it. It is not explained why we should read the two vertically aligned question marks north of Iraq as

saying “a Kurdish state.” The claim is puzzling not only because Lawrence presumably knew how to spell, but also because the northern border of Iraq on his map—which is the Sykes-Picot boundary between the A and B territories—cuts right through the middle of Iraqi Kurdistan, incorporating Sulaymaniyah within the Iraqi state. The empty area with the two question marks on Lawrence’s map is not Kurdistan but the region around and including the city of Mosul.

Clearly, the reason Lawrence’s map is so popular today is that it seems to at least gesture at an effort to align state boundaries with ethnic ones, through the two states, if that is what they are, that he labels “ARABS.” And if that was the logic, then what indeed could Lawrence have used to label Mosul besides a question mark? Lawrence would have known very well that this part of Mosul was not a homogeneous or even a majority Kurdish region but an extraordinarily diverse one, home to significant numbers of Arabs (mostly Sunni, some Shi`i), Kurds (Sunni, Yazidi, and Shi`i), Turkmen (Sunni and Shi`i), Assyrians, Chaldeans, Armenians, and Jews, among others. Of course, anybody even vaguely paying attention to recent events should have some sense of this by now, too.

What these recent events should be teaching us is that following the artificial state narrative to its logical conclusion leads to one place, and that place is not peace in the Middle East but rather the violence of ethnosectarian cleansing. This is part of what IS is doing, in its effort to dismantle the “artificial” borders. Yet rather than compelling the rest of the world to rethink the logic of the artificial state narrative—which is, I repeat, the logic of ethnosectarian cleansing—the violence of IS is being marshaled as yet more evidence of that narrative’s purported truth.

When Iraq was created after World War I, the notion that states should strive for ethnic homogeneity was a new one and far from universally accepted.[9] Some nation-states were indeed formed on variations of this principle during the twentieth century, often through massive forced population transfers and sometimes through more lethal methods. The results were not homogeneous states (that seems to have been impossible everywhere) but rather states with clearly dominant ethnosectarian majorities. It hardly needs stating that, whatever else might be said of this outcome, it did not tend to improve the position of the remaining minorities. In any case, these kinds of projects have fallen out of fashion, at least in international human rights discourse and law; the official UN term for the mild versions (including population transfer) is “ethnic cleansing” and for the more extreme ones “genocide.” The narrative of Iraq as an artificial state, in its dominant manifestation today, draws on the fantasy of ethnosectarian homogeneity as the foundation of stable statehood while refusing to acknowledge the inevitable implications of that fantasy, especially in a region as heterogeneous as Iraq.

Iraqi Border Formation

As for Lawrence’s map, one thing it does tell us is that the British were perfectly aware in 1918—two years after Sykes-Picot—that no new borders had been established in this region, even though by then many lines had been drawn on many maps. British political

actors involved in Middle East questions indeed loved drawing lines on maps; for some, such line drawing was a veritable pastime, if not obsession. But the maps they used were never empty, which after all would have made it a rather boring exercise. They took many things into account: mountains, deserts, rivers, and ports; known and suspected oil deposits; population densities; existing Ottoman borders, both international and provincial; previous treaty agreements and current diplomatic relations and balances of power; military strategies, gains, and losses, especially given the active wars over several of the borders through the late 1920s; and perceived local desires, demands, and conflicts as well as perceived ethnicities, languages, and religious sects.

Thus, from 1914 to 1932 there were many different and competing maps of Iraq drawn in Europe—to say nothing of those drawn in Iraq, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Hijaz, Najd, Kuwait, and Iran. At the time, it was understood by all concerned that these maps were simply proposals and counter-proposals. Only in December 1922, after the latest border treaty between Iraq and Najd had been signed, did the lines being drawn in most of those places (with the significant exception of Turkey) start to look something like the outline of present-day Iraq. This was the result not of the whims of a civil servant in London but rather of the slow and arduous process of resolving competing claims to territory, often through war and always through the use of power. The inclusion of the Ottoman province of Mosul within Iraq, and thus the fixing of the Iraq-Turkey border, was not determined until 1926. It took another six years for Iraq and Syria to agree on their northern border. Border conflicts plagued Iraq’s relations with Iran through the 1930s and beyond. No Iraqi government recognized any border with Kuwait until 1991, when it was forced to do so after the US bombing. In short, Iraq’s borders were formed in much the same way that nation-state borders everywhere have been formed. A lot of work and a lot of violence went into their construction, and a lot of work and a lot of violence would go into their re-construction.

[For extremely helpful comments on earlier versions of this article, I thank Beth Baron, Samira Haj, Dina Rizk Khoury, and Omnia El Shakry.]

‘Lines Drawn on an Empty Map’: Iraq’s Borders and the Legend of the Artificial State (Part 2)

Jun 03 2015by Sara Pursley

[Crop of 1924 map of Mandate territories. All of the borders with dashed lines are defined as “Undetermined” in the key. See below for full map. Image from The Treaties of Peace 1919-1923 (New York: Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace, 1924), 2:966.]

In attending to how local actors shaped Iraq’s formation as a nation-state after World War I, the point is not to deny the power of British imperial forces, or the violence they unleashed on Iraqis during the occupation (1914-1920) and Mandate (1920-1932) periods. On the contrary, I would contend that one effect of the artificial state narrative is precisely to efface British imperial violence while simultaneously denying the impact of non-British, and anti-British, actions. One way this works is by imagining that Iraq’s borders were created on an “empty map” in a European drawing room, perhaps over tea, and not—as all nation-state borders everywhere have been created—through the resolution of competing claims to territory and sovereignty by deployments of power, including acts of insurgency and counterinsurgency.

Three moments in the early formation of Iraq’s borders—specifically those with Syria, Najd (present-day Saudi Arabia), and Turkey—may help illustrate some of the ways in which the process worked. The British played significant roles, and so too did residents of Iraq, Syria, Najd, and Turkey.

Iraq and Syria

The Iraq-Syria border was rather mobile from the end of the war in 1918 to Iraq’s formal independence in 1932, but the concept of Iraq and Syria as separate states was widely accepted. It is often forgotten that the San Remo conference, which was held in late April 1920, was in part a hastily convened response by the colonial powers to the Arab conference in Damascus in early March, which had proclaimed the independence of Syria and of Iraq as constitutional monarchies under two different sons of Sharif Husayn, Faysal and Abdallah, respectively. The Iraq declaration was issued by the Iraqi branch of al-Ahd, often referred to as the “Arab nationalist” party. Formed in late 1918 when the original group split into two, al-Ahd al-Iraqi was led by Iraqi ex-Ottoman military officers based in Syria; by 1919 it also had an active branch in Mosul and a less active one in Baghdad. Its official platform called for “the complete independence of Iraq” within “its natural borders,” which it defined as extending from the Persian Gulf to the bank of the Euphrates north of Dayr al-Zur in present-day Syria and to the Tigris near Diyarbakir in present-day Turkey—that is, rather more territory than included in the Ottoman provinces of Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul.[i] The group also pledged to work within a loosely defined “framework of Arab unity”; this part of its platform is better understood as Arabist than Arab nationalist, as it did not involve any specific territorial or state-oriented imaginary.

By 1919, then, the two branches of al-Ahd were calling for two independent territorial states—Syria, with its capital in Damascus, and Iraq, with its capital in Baghdad. Throughout the 1920 Iraqi Revolt against the British Mandate—which started in May and June, partly in response to San Remo, and involved large areas of northwestern, central, and southern Iraq—this was also the official platform of the other major Iraqi nationalist party, Haras al-Istiqlal (the Guardians of Independence), based in Baghdad and with significant support in the southern Shi`i shrine cities.[ii] What the two parties diverged on was not the demand for an independent Iraqi state stretching from the Persian Gulf to somewhere north of Mosul, distinct from Syria, and with its capital in Baghdad—all of that they agreed on—but rather the question of what kind of foreign assistance the future Iraqi state would rely on. Al-Ahd al-Iraqi’s platform specified that it would rely solely on British assistance, while the platform of Haras stated that independent Iraq could request the assistance of any foreign power it pleased.

This understanding of Iraq and its borders had also been the single point of agreement among notables in the three Ottoman provinces who were involved in the plebiscite organized by Britain in late 1918 and early 1919. While the plebiscite was presented as an effort to ascertain the opinion of the locals on what kind of government they wanted, officers of the British occupation army were directed to produce the desired results by pretty much any means necessary. Thus, in most places, a dozen or even fewer notables believed to be

loyal to Britain were convened and instructed to answer favorably to a set of questions about Iraq’s future. What was remarkable about the plebiscite was not the duplicity of British colonial officials, or the fact that they managed in many places to elicit the outcome they wanted. Rather, it was that in four of Iraq’s most important cities—Baghdad, Najaf, Karbala, and Kadhimiya—they failed to locate even a small group of compliant notables who would deliver a unified opinion accepting British governance over Iraq. In all of these cities, the text of the plebiscite was altered in some way—against explicit British instructions—in order to reject the British occupation and assert Iraqis’ desires for complete independence. The only part of the text that was not rejected or altered in any of the responses was its definition of Iraq as a state stretching “from the northern border of Mosul province to the Persian Gulf.”[iii]

There was no map drawn at San Remo in 1920; the agreement explicitly postponed the determination of the borders. But one thing the European powers did at San Remo was ratify the concept of Iraq and Syria as two states, while Sykes-Picot had divided present-day Iraq and Syria into either three or four states. The 1920 agreement was thus more in line with local nationalist demands, and in particular with the recently declared independence of Iraq and Syria, as well as with historical and linguistic understandings in the Arabic-speaking world of Syria and Iraq as geographical areas, and sometimes as states, loosely centered on Damascus and Baghdad, respectively. San Remo was also an attempt to contain those nationalist demands, by promising the two states only conditional independence, moving toward eventual full independence, under the tutelage of the Mandate governments, France and Britain. The main conflict between local nationalists and the European colonial powers by 1920, at least as far as the Iraq-Syria border was concerned, was thus not over the division of Arab lands into separate states but rather over the degree and timing of those states’ sovereignty. Of course, things were different on Syria’s western and southern borders, given the conflicts over the separation of Palestine, Lebanon, and Jordan from Syria—the first by the time of San Remo, the other two later—and these conflicts may have shaped our understanding of Iraq’s formation.

In terms of establishing the actual whereabouts of the Iraq-Syria border, the main question (leaving aside Mosul for the moment, since that was primarily an Iraq-Turkey, not an Iraq-Syria, dispute) was over the Ottoman province of Dayr al-Zur. In Sykes-Picot, Dayr al- Zur had been placed on the French side of the line between the A and B territories, but the fact that it ended up in Syria was almost a historical fluke.[iv] In November 1918, conflicts between residents of Dayr al-Zur and the officers of the Arab army in Syria led local notables to appeal directly to Britain to annex the region to the occupied territory of Iraq. British troops duly arrived and did so. But soon the residents became resentful of the British occupation as well, and in 1919, petitioned Damascus for re-incorporation into Syria.

Ironically, it was the Iraqi nationalist officers of al-Ahd al-Iraqi who were ultimately responsible for the inclusion of Dayr al-Zur within Syria. They hoped to use the region as a base for launching attacks from Syria on British occupation forces in Iraq—and that is what they did, thereby helping to spark the 1920 revolt.[v] In 1923, Baghdad-based Iraqi nationalist Muhammad Mahdi al-Basir explained the Dayr al-Zur decision: “Iraqis [in Syria] were working for the liberation of Iraq, even if that required annexing much of

its land for the Syrian government.”[vi] Leading British officials, including Acting Civil Commissioner in Iraq at the time, A.T. Wilson, later asserted that Britain’s acquiescence at Dayr al-Zur—i.e., the evacuation of its troops and relinquishing of the province to the Arab army in Syria—helped precipitate the entire 1920 revolt, not only by providing the Iraqi nationalist officers in Syria a base for cross-border military operations but also by giving other opponents of the British Mandate within Iraq a sense of Britain’s vulnerability.[vii]

Iraq and Najd

Iraq’s southern border with Najd (present-day Saudi Arabia) was left completely undefined in most of the international agreements during and after the war, though it does appear in one early map of the Mandate territories (see below). This map—which is titled “Mandates in Arabia” and has been displayed in many popular and scholarly accounts of Iraq as an artificial state—is a good example of some of the pitfalls involved in tracing the history of post-Ottoman borders. At some point, the map started being dated to 1920 and attributed to either the Treaty of Versailles or the San Remo Agreement, thus suggesting that the borders it shows had been established by then. But this date is impossible for numerous reasons, including the map’s depiction of a Transjordan Mandate, which did not exist even as a concept until 1921. In fact, the map was drawn by US geographer Lawrence Martin in 1924, as his personal interpretation of all of the border agreements up to and including the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. In the case of the Iraq-Najd border, however, it actually depicts the situation in early 1922, or at least one plausible interpretation of it. Martin was apparently unaware of that border’s redrawing in the Uqair Protocol signed between Iraq and Najd in December of that year.[viii]

In any case, both the Iraq-Najd and the Transjordan-Najd borders on this map appear considerably south of their current locations. In Sykes-Picot, we may recall, the territory envisioned as British-ruled Iraq extended even further south on the eastern side, encompassing the coastline and a good inland chunk of the Arabian Peninsula down to Qatar. The main factor that undid both of these plans, fixing the border in its more northward location, was the military expansion of Abdulaziz ibn Saud of Najd and his Ikhwan forces during these years. In a series of treaties with Abdulaziz from 1920-1927, British officials acknowledged his ongoing territorial conquests by accepting progressive contractions of their envisioned territories. Britain eventually fought to prevent further northward expansion of the Saudi state, launching a massive air offensive into recognized Najdi territory to that end in 1927-1928. Britain’s line in the sand, as it were, was its determination not to lose what remained of the corridor linking its Iraq and Transjordan mandates, which in the British view had already been dangerously narrowed by Abdulaziz’s recent conquests.[ix] The image below shows a rough outline of the Iraq-Najd border as of 1927, when the British air force finally halted the Saudi advance.

Rather than a line on an empty map, the border was defined in the treaties as a series of lines connecting known waterholes or wells in the desert. The placement of the border on one side or another of each well determined the nationality of the nomadic people living in the borderlands. If a well was placed on the Iraq side, the members of the tribe to which that well was locally understood to belong became Iraqi subjects; otherwise, they became subjects of Najd. The placements themselves were not arbitrary either, since British and Iraqi officials and Abdulaziz all had very strong ideas about which tribes they wanted and did not want as subjects, and negotiated over those that were claimed by both. The tribes also had some say in the matter; a few successfully resisted their new nationality and were transferred to the other side.

Iraq and Turkey

The dispute over the Ottoman province of Mosul was by far the most significant border question in the formation of modern Iraq. When Britain occupied Mosul on 3 November 1918, and then declined to leave, it was breaking two agreements: its Sykes-Picot Agreement with France, according to which Mosul was to be under French influence, and the Armistice of Mudros, signed on 30 October 1918, which officially ended World War I in the Middle East by ending hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the Allied powers. Since Britain occupied Mosul four days after the signing of the armistice—i.e., when it was not at war with the Ottoman Empire—first the Ottoman and then the Turkish state naturally refused to recognize the legal validity of the occupation and thus Mosul’s incorporation into Iraq.

While Britain ultimately succeeded in including Mosul within Iraq, an important factor in establishing the Iraq-Turkey border, and one that is often forgotten, was the Turkish War of Independence. The history of Turkey’s southern border from 1918-1923 is far too complicated to recount here, but suffice it to say that the Treaty of Sèvres, which was forced on the Ottoman state in August 1920, left Turkey as a small rump state in central Anatolia. The British- and French-influenced territories were extended northward well into present-day Turkey through a semi-independent, possibly Kurdish, state or zone; the map above shows Lawrence Martin’s interpretation of Sèvres. This treaty helped fuel the Turkish War of Independence, in which Kemalist forces defeated the Allies and reclaimed much of the land that had been lost since the 1918 armistice, pushing the borders south once again. In this case, the borders were thus imposed on the European powers rather than by them. If the Kemalists had been defeated, we might now be hearing that Europeans drew the borders of the modern Middle East at Sèvres rather than in San Remo or Sykes-Picot.

The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which ended the Turkish War of Independence, established most of Turkey’s present-day borders, but not the one with Iraq, since neither Turkey nor Britain would budge on Mosul. The agreement specified that the two parties would attempt a peaceful resolution of the dispute, and if that failed within nine months, the question would be referred to the League of Nations, which it was. After a commission appointed by the league toured Mosul in 1925 to ascertain local opinion, it recommended that the province be given to Iraq. Turkey appealed the decision, but it was upheld and in 1926 Turkey signed the agreement establishing its border with Iraq. King Faysal of Iraq proclaimed that the treaty “fixes our political existence, internally and externally.”[xi] He was right, of course, since mutual recognition—usually of a resolution to competing claims to territory—is what a border is, or in any case what makes one possible. It takes at least two.

Both British and Iraqi officials had worked hard for eight years to break Mosul away from Turkey. The British air force had engaged in near-continuous air bombing campaigns, often described in British primary sources, and repeated in many secondary sources, as defensive actions against Turkish “incursions” into Iraq. Since Mosul did not yet belong to Iraq, however, this may be a questionable description. The bombings targeted both pro-Turkey borderland communities and Kurdish separatists. As one British report explained:

[The] Arab and Kurd … now know what real bombing means, in casualties and damage; they now know that within 45 minutes a full sized village … can be practically wiped out and a third of its inhabitants killed or injured by four or five machines which offer them no real target, no opportunity for glory as warriors, no effective means of escape.[xii]

More diplomatic measures were also used. The Mandate government issued statements from Baghdad promising that minority languages and rights in the north would be respected, and delegations of Iraqi officials toured Mosul and Sulaymaniyah to persuade residents they would be better off in Iraq than Turkey, especially as the date approached for the arrival of the League of Nations commission.

In fact, from 1918 to 1926 Mosul acquired profound significance in the formation of an Iraqi national identity, a process that has received inadequate attention and is thus poorly understood. Already in the 1918-1919 plebiscite, as both Iraqi and British observers noticed at the time, the only unanimous point of agreement was that “Mosul is part of Iraq,”[xiii] and in the coming years nationalist poets in Baghdad and Basra waxed lyrical about Mosul as the “Jewel of Iraq.” Iraqi officials mobilized these sentiments to counter nationalist critiques of the Mandate relationship; Prime Minister Abdul Muhsin al-Saadun asserted that Mosul was the “head” of the “body” of the Iraqi nation, and King Faysal declared that the Mosul question was “a life or death matter for our beloved country.”[xiv] British officials were also cognizant of them, repeatedly using Mosul as both carrot and stick for bringing nationalists in Baghdad and the southern regions into line. Most dramatically, they threatened not to support Iraq’s case at the League of Nations on the Mosul dispute if the Iraqi government did not ratify the treaty with Britain ensuring the latter’s authority over Iraq’s affairs. There was much debate among Iraqi nationalists at the time over whether Britain was bluffing—after all, it had major oil interests in the province—but

many did not think it was a risk worth taking, especially after Turkey offered Britain the same rights to oil in Mosul that it would have with Iraq. Faysal asserted that it would be “a terrifying gamble to take with the most glorious part of our nation.”[xv] When the Iraqi Constituent Assembly finally ratified the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty in 1924, under intense British pressure, it made its approval conditional on “the British government’s protection of Iraq’s rights over the province of Mosul in its entirety.”[xvi]

As for Mosulis, they were deeply divided between pro-Turkey and pro-Iraq sentiments throughout these years, with some moving back and forth across the divide according to their evaluation of rapidly changing conditions. For some, especially Armenians and other Christians, communal affiliations often did drive political allegiance; Turkey was a hard sell after the genocide and the Turkish- Armenian War. Others—and perhaps especially the Kurds—were split, a division complicated in the Kurdish case by the existence of a third faction proposing an independent Kurdish state. This faction was more or less vocal at different moments and in different regions, but never unified enough to stand a chance against the British air force. For Arab Mosulis, communal/linguistic affiliations and even Arabist commitments did not necessarily determine political alignments. For example, a dispute broke out between the Mosul and Syria-based branches of the Arabist-oriented al-Ahd al-Iraqi when the Mosul group announced that many Mosulis were looking to Turkey and suggested that Iraqis in general would be better off allying with the Kemalists (and the Bolsheviks) than with Hijazi Arabs such as Sharif Husayn and his sons.[xvii] For all Mosulis, the dispute was constantly complicated by the fact that there were two conflicting imaginaries of “Iraq”—the British one and the independent one.

It might be noted that the possibility of Mosul’s incorporation into Syria was not a major topic of discussion from 1919-1926, since that was not one of the options on the table, Sykes-Picot notwithstanding.[xviii] Decades-long scholarly speculation about whether Mosul might have been more “naturally” joined with Syria is thus beside the point. The actual historical problem was that Britain was militarily occupying the province, and wanted it to be part of Iraq—as did Iraqi government officials and anti-British Iraqi nationalists—while Turkey had a very strong legal claim to it given that the British occupation had been in violation of international law. Nobody seriously proposed that a secret wartime agreement between Europeans had given Syria or France any internationally or locally recognizable claim to Mosul, despite some short-lived grumbling by French officials about the wartime actions of their ally (smoothed over in any case by 1920, after Britain promised France a future share in Mosul’s oil). The notion that there is some Archimedean vantage point from which international borders can be, or ever have been, created is obviously nonsense. But it is a notion that the “fabricated in Europe” narrative has helped to sustain, perhaps in spite of itself, by perpetuating the idea that the act of drawing a line—any line at all—on a map in Europe has the quasi-magical power to create a border in Asia. That historians have contributed to this story may have something to do with what Neil Smith has argued was the increasingly “anemic” conception of geography within the academic discipline of history, at least in the United States, over the course of the twentieth century.[xix]

The Emergence of the Artificial State Narrative

While the narrative of Iraq as an artificial state resonates with similar discourses on other postcolonial states—especially in the Middle East and Africa—it has its own particular history. It emerged in the earliest years of the state’s formation, and was connected to claims of the ungovernability of Iraqi subjects: the rural ones because they were tribal and uncivilized, the urban ones because they were ethnically and religiously heterogeneous. It was originally a colonial narrative, used to justify Britain’s continuing occupation of Iraq. As early as 1922, the London Times expressed the emerging suspicion that there was something scandalous about Iraq: “No common purpose yet animates these heterogeneous communities . . . Mesopotamia, with its vague frontiers and mixed population, was treated as a nation, as an embryo State, to be ranked with the modern democracies included under the League of Nations.”[xx] This argument, it bears remembering, was an explicit response to Iraqi nationalist demands for sovereignty. Acting Civil Commissioner A.T. Wilson had been in charge of putting down the 1920 nation-wide revolt that demanded the evacuation of British troops and the “complete independence” of Iraq within its “natural borders,” at the cost of over eight thousand Iraqi lives and five hundred British and Indian ones, according to British estimates. Yet in his 1931 memoirs, he claimed that in the period 1917-1920, nationalism “was not an important element in Iraq . . . the idea of Iraq as an independent nation had scarcely taken shape, for the country lacked homogeneity, whether geographical, economic, or racial.”[xxi] He even cited older British sources to support these claims, quoting the Marquess of Salisbury in 1878 that “Asiatic Turkey contains populations of many races and creeds, possessing no capacity for self-government and no aspirations for independence.”[xxii]

Iraqi officials invoked similar narratives for various purposes throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In 1932, the year Iraq became formally independent and joined the League of Nations, King Faysal proclaimed:

In my opinion, and I say this with a heart full of sorrow, an Iraqi people does not yet exist in Iraq. There are only throngs of human beings lacking any national consciousness, immersed in religious traditions and falsehoods, disunited, susceptible to evil, inclined toward anarchy, and always prepared to rise up any government whatsoever.[xxiii]

This quote has been widely invoked over the years as further evidence that Iraq itself is some kind of scandal. Faysal’s next lines are often not included: “This being the situation, we want to fashion these multitudes into a people that we will cultivate, guide, and educate . . . This is the people I have taken it upon myself to bring into being.”[xxiv] Like most nation-builders of his time, Faysal understood very well that nation-states are constructed—which, for nation-builders, means that they have to be constructed.

But it might also be productive to focus less on what such quotes say about Iraqis than on what they were invoked to do in the context in which they were uttered. Of course, Iraqis in the first decade of Iraq’s existence were not rising up against “any government whatsoever,” as Faysal claimed. They were rising up against Faysal’s government, including the British Mandate system that propped it up. The discourse of Iraqis as inherently ungovernable submerged all conflicts in Iraq into a single, ready-made explanatory narrative, as the discourse of the artificial state continues to do today.

In the 1920s and 1930s, what this discourse may have been most concerned with submerging and forgetting was the 1920 revolt. The contemporary sources on this revolt simply do not support the notion that Iraq was a colonial imposition. The consistent demand of the insurgents, from Mosul to Baghdad to the southern Shi`i shrine cities, was Iraq’s complete independence—al-istiqlal al-tamm—within what they called its “natural borders,” which they defined as extending from north of Mosul to the Persian Gulf.[xxv] This does not mean that all Iraqis participated in the revolt, but rather that most of those who did were protesting the British military occupation and the British Mandate, not the drawing of Iraq’s borders and its formation as a nation-state. At the time, the notion of Iraq’s inauthenticity was almost exclusively a colonial discourse.

Fortunately for Iraqis, the small cohort of British officials who argued after the war that the new state borders should be based on ethnosectarian ones lost the battle; Iraq therefore witnessed no major projects of ethnic cleansing in the 1920s. As I have suggested, many factors contributed to this outcome, including Iraqi nationalist demands, British imperial interests, and the actions of Iraq’s neighbors. Critics of the argument also frequently pointed out the extreme difficulty of implementing an ethnosectarian vision in this region. Indeed, it was this vision that drew its logic from the fantasy of an empty map, or a map filled with empty homogeneous space: empty of history; of claims to territory and other resources; of neighbors speaking different languages; of multiethnic villages and virtually any conceivable city; of existing provincial and international borders; of previously concluded treaties and agreements; of local and international laws; even of mountains, rivers, deserts, and oil deposits. Nothing but empty space and fixed ethnosectarian identities.

But that point was made a hundred years ago. What I have also been suggesting is that the narrative of Iraq as an artificial state emerged out of the very historical conflicts and processes it was then retrospectively deployed to explain, as well as to explain away. Rather than historicize the narrative, by exploring its emergence in the years after World War I, scholars and countless other commentators have used and re-used it to empty Iraq of history

Source: http://www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/21759/lines-drawn-on-an-empty-map_iraq’s-borders-and-the

Comment here