Download PDF Tariq Shafiq- Researched Highlight of the Oil Matrket

Generally speaking, oil prices go up when the global economy is robust, world demand is rising, suppliers are pumping at maximum levels, and little stored or surplus capacity is on hand. They tend to fall when, as now, the global economy is stagnant or slipping, energy demand is tepid, key suppliers fail to rein in production in consonance with falling demand, surplus oil builds up, and future supplies appear assured.

• During the go-go years of the housing boom, in the early part of this century, the world economy was thriving, demand was indeed soaring, and many analysts were predicting an imminent “peak” in world production followed by significant scarcities. Not surprisingly, Brent prices rose to stratospheric levels, reaching a record $143 per barrel in July 2008. With the failure of Lehman Brothers on September 15th of that year and the ensuing global economic meltdown, demand for oil evaporated, driving prices down to $34 that December

• Several factors account for this price recovery, none more important than what was happening in China, where the authorities decided to stimulate the economy by investing heavily in infrastructure, especially roads, bridges, and highways. Add in soaring automobile ownership among that country’s urban middle class and the result was a sharp increase in energy demand. According to oil giant BP, between 2008 and 2013, petroleum consumption in China leaped 35 percent, from 8.0 million to 10.8 million barrels per day. And China was just leading the way. Rapidly developing countries like Brazil and India followed suit in a period when output at many existing, conventional oil fields had begun to decline; hence, that rush into those “unconventional” reserves.

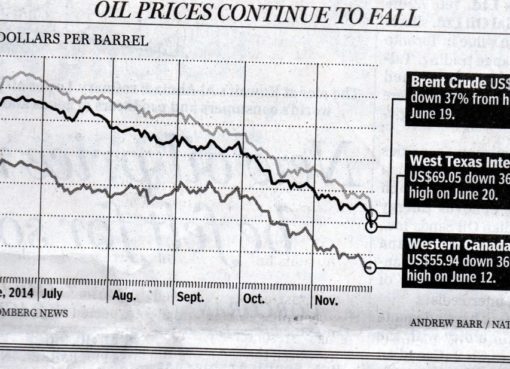

• This is more or less where things stood in early 2014, when the price pendulum suddenly began swinging in the other direction, as production from unconventional fields in the U.S. and Canada began to make its presence felt in a big way.

Many reasons have been given for the Saudis’ resistance to production cutbacks, including a desire to punish Iran and Russia for their support of the Assad regime in Syria. In the view of many industry analysts, the Saudis see themselves as better positioned than their rivals for weathering a long-term price decline because of their lower costs of production and their large cushion of foreign reserves

Opec lead by Saudi Arabia is determined not to cut production as a way to prop up prices. Saudi Arabia await A period of lower prices were to force some higher cost producers to shut down, then Riyadh might hope to pick up market share in the longer run. This time it hasn’t. In a historic move at the end of last year, Opec said not only that it would not cut production from its 30 million barrels a day (mbpd) quota, but had no intention of doing so even if oil fell to $20 per barrel; a point which the market is close to calling for the intended reversal.

There could be two reasons – to try to instil some discipline among fellow Opec oil producers, and perhaps to put the US’s burgeoning shale oil and gas industry under pressure.

RUSSIA IS VUNERABLE:

Although Saudi Arabia needs oil prices to be around $85 in the longer term, it has deep pockets with a reserve fund of some $700bn – so can withstand lower prices for some time.

Russia is one of the world’s largest oil producers, and its dramatic interest rate hike to 17% in support of its troubled rouble underscores how heavily its economy depends on energy revenues, with oil and gas accounting for 70% of export incomes.

Russia loses about $2bn in revenues for every dollar fall in the oil price, and the World Bank has warned that Russia’s economy would shrink by at least 0.7% in 2015 if oil prices do not recover. A period of lower prices were to force some higher cost producers to shut down, then Riyadh might hope to pick up market share in the longer run.

The most likely explanation, though, and the one advanced by the Saudis themselves is that they are seeking to maintain a price environment in which U.S. shale producers and other tough-oil operators will be driven out of the market. “There is no doubt about it, the price fall of the last several months has deterred investors away from expensive oil including U.S. shale, deep offshore, and heavy oils,” a top Saudi official informed the Financial Times last spring.

USA IS THE WINNER TO A LIMIT

Shale has essentially severed the linkage between geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East, and oil price and equities. Even though many US shale oil producers have far higher costs than conventional rivals, many need to carry on pumping to generate at least some revenue stream to pay off debts and other costs. However, they are bound to continue as long as the price pays for their cost; the operating cost (Opex), which is far below the much higher capital investment cost (Capex). However, I have no knowledge of their numerical split.

Despite the Saudis’ best efforts, the larger U.S. producers have, for the most part, adjusted to the low-price environment, cutting costs and shedding unprofitable operations, even as many smaller firms have filed for bankruptcy. As a result, U.S. crude production, at about 9.2 million barrels per day, is actually slightly higher than it was a year ago.

“We have entered a new chapter in the history of the oil market, which is now starting to operate like any non-cartel commodity market,” says Stuart Elliott at energy specialist Platts.

The cartel was in fact the work of the Seven Sister, the major oil companies who managed an international horizontal (world wide) and vertical (from the producing end to the consuming gasoline stations) integration, which diminished with the end of concession era.

Shale has essentially severed the linkage between geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East, and oil price and equities. Even though many US shale oil producers have far higher costs than conventional rivals, many need to carry on pumping to generate at least some revenue stream to pay off debts and other costs.

HOWEVER:

Questions are also being asked about fracking. Costs vary a great deal, but research by Scotiabank suggests the average breakeven price for US shale producers is about $60. At the same price, energy research group Wood Mackenzie estimates that investment in new wells would halve, wiping out production growth.

“The vast majority [of US shale wells just don’t work at $40-$50,” says Mr Cronin.

Oil majors are already suffering, having announced tens of billions of dollars of cuts in exploration spending. But while the share prices of BP, Total and Chevron are all down about 15% since last summer, the majors have the resources to see out a sustained period of low oil prices.

There are hundreds of other much smaller oil groups across the world with a far more uncertain future, not least in the US. Shale companies there have borrowed $160bn in the past five years, all predicated on selling oil at a higher price than we have today. Banks’ patience can only be tested so far.

Oilfield services companies are also “feeling severe pain”, according to Mr Whittaker, with share prices in the sector down an average30%-50%. Last month, US giant Schlumberger announced 9,000 job cuts, some 8% of its entire workforce.

But it’s not just oil companies that are being hit by lower oil prices – the renewables sector is suffering as well.

The conclusion: No one country has a magic whip on prices. But major exporters influence supply and major consumers naturally influence supply and accordingly prices. USA and associate Saudi Arabia can and do influence, but not dictate. But that influence is limited as market fundamentals take over.

If any one state can dictate the fate of the global market, it is absurd that party cuts its nose to despite its cheek by inflicting damage in other ways on its companies and global economy!

(*) Mr. Tariq Shafiq is a senior Iraqi oil expert and former executive of Iraqi National Oil Company (INOC)

Copyright: Iraqi Economists Network. Posted January 24, 2016

Dear Tariq, this is an excellent dispose, and I would, largely, agree with your objective pretensions, but, apart from supply and demand, there is a role for the political enter-plays; US versus Russia and Iran; Saudi Arabia versus Iran, and, perhaps Iraq. Again, oil substitutes are now almost out of the lid. Yet, other things being equal, ceteris paribus, the conditions of the oil suppliers are less favourable than the oil demanders. I thank you for this very concise and intelligent piece of contribution.

Kamil Aladhadh.