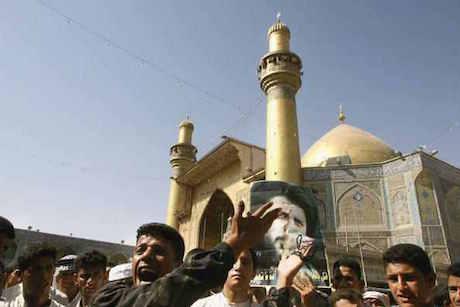

When the US invaded Iraq in 2003 it subsequently disbanded the country’s army, dismantled its security infrastructure and instituted an extensive set of occupation policies, all apparently geared at making it the main political, security and economic actor in the country. The consequences of those early policies and actions have radically transformed Iraq over the past few years, effectively turning it into a theatre for the playing out of domestic and regional contestations. One such emerging struggle over the future of Iraq, particularly for the devout Shi’a both inside and without the country, has been tracked by what has since happened to Iraq’s revered shrine cities of Karbala and Najaf.

Seeing itself as the new permanent power in Iraq – effectively a new state order – the US actively engaged in state wrecking rather than institution building. The occupation viewed Iraq as conquered territory and at this early stage. in 2003 and 2004, US hegemonic power over the country seemed impregnable. Iraq’s state institutions were in tatters and as a result, new and often multiple conflicts unfolded across the country.

Notwithstanding organised violence against the occupation, which sought to upend US plans of making Iraq a client state, another set of foreign-devised policies were also being enacted. Specifically, shrine cities were now facing the onslaught of Iranian plans to undermine Iraq’s Shi’a clergy (ulama), particularly Najaf’s clerical establishment (marja’iyah), which constitutes a potential source of competition to Iran’s own Shi’a religious and political authorities.

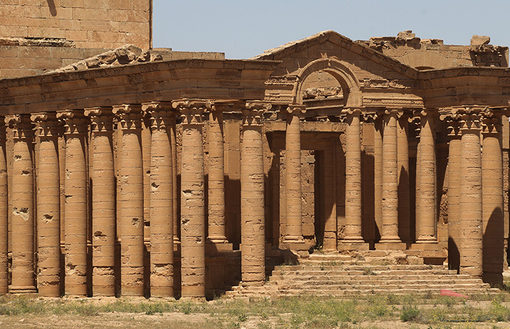

The invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the forced collapse of its state institutions had provided a rare opportunity for the Iranian government, which now sought to win what has long been a historical struggle for the control of Najaf and Karbala, the main sites of Shi’a learning in the world. According to renowned scholarYitzak Nakash, the historical contestation in Iraq between Shi’a Arabs and Shi’a Iranians, or Persians, was fought over the control of Karbala and Najaf. The author, reviewing the past two hundred years, states that “in Karbala and Najaf, the Persian religious families managed to overshadow the Arab ulama and succeeded in dominating religious circles….by the mid-nineteenth century, the Persian ulama in Iraq had already controlled most of the Shi’a charitable funds and the madrasas…”

Beneath the veneer of a hegemonic America in an occupation that largely focused on its own security situation, was this enactment of an Iranian plan to control Shi’a Islam’s holiest sites. The Iraq war and the changed politics brought about by the occupation, particularly in the wake of the vacuum the US had created in the country, allowed this battle for control of Iraq’s religious sites to play itself out.

Historically, the clerical class in Iraq have relied on two sources of finance; namely, money from religious tourism and pilgrimage as well as from the transportation, care and burial of the Shi’a dead, particularly in Najaf’s Wadi al Salam, the world’s biggest cemetery. According to Nakash, the “flow of foreign money to the shrine cities had major consequences on their political orientation and socioeconomic organisation. The shrine cities developed an economy based on charities and payments for religious services, and on the income from the pilgrimage and the carriage of the dead.”

Whilst the political economy of Najaf and Karbala had been much affected by previous historical turning points, such as the establishment of the Iraqi state in the 1920s, then the impact of Saddam Hussein’s regime, as well as international sanctions in the 1990s, the post-2003 developments once again altered the order of things.

under and after the US occupation of Iraq the Iranian government resorted to controlling, albeit indirectly, Najaf and Karbala, which was the most secure way to realise its objectives

Specifically, a calculated set of Iranian interventions that had not been witnessed for over a century was now implemented in Iraq. Such interventions were designed for the long-term dominance of Karbala and Najaf, and were largely economic in nature rather than overtly political or religious. Sources of funding, divided between different and often competing Iraqi Shi’a clerical schools, have historically ensured that Iraq’s marja’iyah enjoyed a degree of autonomy from the whims of politicians who sought to influence the devout Shi’a in ways conducive to their own interests. For Iran, such autonomy from itself and its policies could not be tolerated, but also could not be attacked head-on. As a result, under and after the US occupation of Iraq the Iranian government resorted to controlling, albeit indirectly, Najaf and Karbala, the most secure way to realise its objectives.

Iran’s political system is based on Khomeini’s Wilayat al Faqih, an arrangement that champions an Iranian-based religious authority and figure of emulation in Shi’a Islam. After 2003, the Iranian government, cognizant of the new freedoms that Iraq’s clergy could exercise, moved to ensure that it did not undermine Iran’s own religious authority in Qum – its centre of religious legitimacy – on which the post-1979 state ideology is premised. For the Iranian government, its priority was to ensure that it was the source of Shi’a legitimacy, and not Najaf, whose leading clerics have promoted the separation of religion from the state.

The empowerment of an autonomous Shi’a clerical establishment in Karbala and Najaf after 2003 would soon be undermined by Ithe carrying out of a concerted set of Iranian policies to control its economies. As a result, the economies of Karbala and Najaf have since been tightly controlled by Iranian state and private companies. Iran’s state-owned tourist companies have invested heavily in controlling and managing the religious pilgrimage to Karbala and Najaf, particularly as a way of ensuring that Iranian pilgrims spend as little of their resources as possible in Iraq. Iran’s private sector investors have also been encouraged to invest in such things as hotels and consequently have become key actors in the hospitality industry in these cities.

The provision of substantially reduced prices for accommodation and food, as well as transport to Iraq, especially for Iranian pilgrims, have all been heavily regulated in ways to reduce a leakage of Iranian foreign currency that the government fears could end up strengthening Iraq’s marja’iyah, which could in turn tap into historically significant streams derived from pilgrim’s money. Iran’s consulates in each of the shrine cities, play a key role in enforcing these structures. More recently, in November 2015, over half a million Iranian pilgrims crossed Iraq without paying the $30 visa fee. In addition, Karbala’s and Najaf’s agrarian economies and light industries have also been decimated by subsidised goods coming from Iran. Such policies amount to a concerted policy to undermine the independent growth of anything outside the direct controlling influence of Iran.

From 2003, Iraqi Shi’a-based political parties, such as the Islamic Supreme Council and the Sadrist Movement, were now not only competing to capture as much of the remaining state institutions and resources that the US had neglected to care for, but were also clashing with each other to capture the shrine cities for themselves. Their participation in national and provincial elections legitimised their actions, tying politics and religion ever closer together. Their efforts saw them develop religious, political and security wings, not unlike a state authority. Each political party championed its own version of Shi’a authority, based on familial lineages stemming from deceased and respected figures of Shi’a emulation, or Mar’ajah. Captured state funding from key Iraqi ministries that such parties were able to control was recycled back to Najaf and Karbala with a view to strengthening the political, religious and economic bases they had worked to build, but also importantly as a way to compete with Iranian goals over Iraq’s shrine cities.

As a result, the blurring of lines between religion and politics became very clear, troubling and creating discord in the marja’iyah in Najaf. In this emerging environment,Grand Ayatollah Syed al Sistani, the figure of authority in Iraq and the Shi’a world, was compelled to distance himself over recent years from both domestic political parties as well as Iranian action. As the highest source of legitimacy for the majority of devout Shi’a, al Sistani has often found himself carefully negotiating the actions of Iraq’s political parties and Iran itself who both vie for the seat of religious power.

At the age of 85, al Sistani will soon be succeeded by those currently competing for Najaf’s influence. Whoever becomes the next figure to take over his authority however, whether Iraqi Arab Shi’a or Iranian Shi’a, will have to deal with an economic environment heavily influenced by the outcomes of long-term and carefully calculated Iranian government interventions.

by

Source: https://www.opendemocracy.net/arab-awakening/mehiyar-kathem/troubling-political-economy-of-iraq-s-sh-ia-clerical-establishment

Comment here