Politically sanctioned corruption and barriers to reform in Iraq. By Toby Dodge and Dr Renad Mansour

This paper explores the pernicious effects of politically sanctioned corruption on governance in Iraq. This type of corruption is more consequential for the coherence of the state, and for its everyday functioning, than petty or personal corruption. It is the key barrier to reform. The post-2003 ethno-sectarian power-sharing arrangement – designed to ensure communal stability – instead sustained an elite pact in which political parties captured and compromised formal institutions of state.

One key feature of this type of corruption has been the abuse of the ‘special grades’ scheme within the bureaucracy, with political parties competing to appoint officials to senior civil service positions to then divert state resources for their own purposes. Their links to party bosses make these civil servants the real decision-makers in ministries and agencies, and release them from any accountability.

Without a fundamental grasp of the dynamics of power across the whole Iraqi system and then a coherent effort to make the civil service more accountable, any local or national reform effort will not succeed.

- Summary

- 01 Introduction

- 02 The post-2003 Iraqi state

- 03 Rethinking corruption in Iraq

- 04 The expansion of the special grades scheme

- 05 The consequences of power: politically sanctioned corruption

- About the authors

- Acknowledgments

Summary

- To aid understanding of the barriers to reform of Iraq’s state and economy, this paper focuses on the drivers and impact of politically sanctioned corruption in the country. This type of corruption has become far more consequential for the coherence of the state, and for its everyday functioning, than petty or personal corruption.

- Politically sanctioned corruption is facilitated in part through the ‘special grades’ (al-darajat al-khasa) scheme, in which ruling parties compete to appoint senior civil servants to oversee, among other things, the tendering of contracts. Operating under the protection of the political parties, these bureaucrats ensure that resources flow from ministries and state institutions to their patrons. They also serve as chokepoints, blocking contracts if they do not benefit the parties concerned.

- The special grades scheme effectively means that power in Iraq does not reside in the formal, transparent and hierarchical institutions of the state, or with the official heads of ministries. Rather, political power lies with political parties and their loyalists (in the latter case, this means senior civil servants generating revenue for their parties from state coffers).

- International policymakers have expressed frustration at their own inability, when taking part in formal diplomatic processes, to engage with the real power-holders in the Iraqi state. This is because Iraqi ministers, from the prime minister down, face constraints that do not allow them to enact reform policies which they profess to favour.

- Rather than seeking to understand Iraqi politics and the state in hierarchical, institutional, legal and rational terms, international and domestic policymakers should encourage reform only once they have a fundamental grasp of how the dynamics of power work across the whole Iraqi system. This requires mapping not only the networks of ministers and government leaders they deal with on a day-to-day basis, but also the positions and influence of the senior civil servants who run state institutions.

- As the demonstrations that dominated Baghdad and the towns and cities of southern Iraq from October 2019 onwards showed, politically sanctioned corruption is one of the major drivers of popular alienation in Iraq. Until meaningful constraints are placed on such corruption, Iraq’s ruling elite will find it difficult to re-establish any form of popular legitimacy or stabilize the country.

01 Introduction

Politically sanctioned corruption in Iraq is a key impediment to good governance – and all the more intractable a problem for being embedded into the country’s elite pact.

‘My signature is just a rubber stamp after contracts are already approved.’ In a discussion in Baghdad during the research for this paper, an Iraqi cabinet minister explained to the authors that every Sunday he would convene his weekly team meeting at his ministerial office and that, much to his initial surprise, his assistants would tell him to sign certain contracts and block others. When he challenged or questioned a contract, he was met with resistance from some of his employees, on whom he depended to run the ministry. If he went further and overturned a decision, relying on his formal powers as the most senior authority in the ministry, he would start to receive phone calls and text messages. In these communications, the heads of the major political parties – which controlled the ministerial assistants whom the minister had attempted to overrule – would threaten the minister.

The constraints described above are not an anomaly in Iraq – they are a product of the country’s political system. Many Iraqi government ministers have publicly expressed frustration at their inability to use the power they should have as the heads of state institutions to make decisions or pursue specific policy agendas. Instead, their own employees – empowered through political parties – effectively act as decision-makers.

Under Iraq’s post-2003 political system, the process of forming a government after an election involves parties competing for influence in each government ministry – and for the resources each commands. This system functions as a kind of elite pact. It ensures that parties are rewarded for their participation in the electoral process by becoming members of governments of national unity. These dynamics, originally put in place to democratize the country in the aftermath of the regime change that accompanied the US-led invasion, govern Iraq’s political system today.

In the early years of this system’s existence, a lot of political attention focused on the commanding heights of the formal state. Parties competed for the ‘three presidencies’ – the positions of president of the republic, prime minister and speaker of parliament – as well as for ministerial appointments and the chairs of powerful commissions. During these early years, controlling the appointment of a particular minister meant gaining power over the relevant ministry.

Over the years, Iraq’s political parties have pushed the politicization of formal state institutions further down into the bureaucracy. Across government institutions, from cabinet ministries to independent commissions, parties place loyalists in positions where they serve the interests of the party before those of the state or the wider Iraqi population.

One area where this competition for senior civil service positions has become significant is in the ‘special grades’ (al-darajat al-khasa) scheme. Hundreds of officials in politicized special grades, spread across all the formal institutions of the state, have dominated Iraq’s government with impunity since at least 2005, following the first national election after the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime. In competition with each other, members of the special grades use the assets of the ministries in which they work to benefit the parties they represent.

Although some ministers are independent technocrats and nominally above the demands of party politics, in reality they often act at the behest of the civil servants who run their ministries.

Today, although some ministers are independent technocrats and nominally above the demands of party politics, in reality they often act at the behest of the civil servants who run their ministries. As such, a minister’s signature on a government contract issued by a particular ministry becomes little more than a rubber stamp, formalizing a deal concluded behind the scenes by assistants aligned to a particular political party or parties. Alternatively, these civil servants at times act as chokepoints stopping ministerial decisions.

This approach to the formation of governments and the subsequent functioning of the state has led to a rapid expansion in government payrolls, the political sanctioning of endemic corruption, and the balance-of-payments crisis in which the Iraqi government currently finds itself. The nature of this political system and its entrenchment in public life mean that meaningful and sustained economic reform will be very difficult to achieve.

The mass protests that dominated Baghdad and southern Iraq from October 2019 onwards – known as the ‘October Revolution’ or ‘October Uprising’ – focused specifically on this political system. Unlike in previous protests since 2009, the young demonstrators were not principally demanding better services or employment. Nor were they calling for the removal of a specific political party or leader. Instead, they demanded the end of muhasasa – the ethno-sectarian power-sharing process that they blamed for the failings of the post-2003 political system. These protesters were the first major group within Iraqi society to conclude that the main barrier to reform is not primarily personal or petty corruption or an excess of power in the wrong hands. They took aim instead at the mechanics of the system itself, and at how it enables the major political parties to share wealth and power gained through corrupt access to the Iraqi state.

International policymakers have expressed repeated frustration at their inability, when taking part in formal diplomatic processes, to engage with the real power-holders in Iraq. They understand that ministers, from the prime minister downwards, face constraints that do not allow them to enact reform policies which they profess to favour. Power in Iraq does not reside in the formal, transparent and hierarchical institutions of the state, or with the official heads of ministries. Rather, power lies with political parties and their loyalists, the latter being senior civil servants who generate revenue for their party political sponsors from state coffers.1

To understand the barriers to reforming Iraq’s state and economy, Iraqi and international policymakers must focus on the role of politically sanctioned corruption in the country. In part, this means looking at the use of the above-mentioned special grades in the civil service, as these have become a core mechanism of party power within the institutions of the state.2

About this paper

This paper traces the evolution of the post-2003 political system, with the special grades as a critical component, and its implications for the sustainable reform of the state in Iraq. Chapter 2 argues that Iraq’s power-sharing system – although designed to reduce ethno-sectarian tensions – has encouraged corruption by enabling political parties and their loyalists from all sects and ethnicities to capture key state institutions. Chapter 3 then argues that researchers and policymakers have often understood corruption in Iraq primarily as driven by personal greed. However, politically sanctioned corruption is in fact the main driver of all forms of corruption. Chapter 4 traces the evolution of the special grades system to the present day. Finally, Chapter 5 offers recommendations for policymakers seeking to engage in Iraq. Its point of departure is to suggest that the root of corruption in the country is the political system – with schemes such as the special grades at its centre.

Figure 1. Timeline of key political developments and the rise of the special grades, 2003–20

02 The post-2003 Iraqi state

Iraq’s power-sharing system was designed to reduce ethno-sectarian tensions. But it has encouraged corruption by enabling political parties, and their loyalists from all sects and ethnicities, to capture key state institutions.

The ethos of national unity

The political parties that have dominated Iraq since 2003 were not created in the aftermath of regime change. Nor was the system that would shape post-Saddam governance. The framework of what would become Iraq’s new political system emerged much earlier, from a series of meetings held throughout the 1990s among members of the Iraqi opposition – primarily consisting of a mix of exiled parties: the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), the Iraqi National Congress (INC), Iraqi National Accord (INA) and the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI).

Following these meetings, the parties agreed on a new political system defined by identity-based power-sharing – or informal consociationalism – which would become known in wider popular discourse as muhasasa taifiya.3 The opposition leaders used this concept to argue that governance after Saddam would be more representative of Iraq as a whole if it was based on the ethnic and religious identities that the Baath Party had repressed.

The key moment when this disparate group of formerly exiled political parties came together to enact this concept and form an elite pact to run Iraq was in July 2003. Based on advice from the UN secretary-general’s special representative in Iraq, Sérgio Vieira de Mello, they formed the Iraqi Governing Council (IGC). The IGC was organized by the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), the US-led occupation authority. At this point, the focus of those seeking power was at the elite level. The formerly exiled political parties dominated the process of selecting the IGC’s 25 members. The parties demanded from the CPA, and were granted, the right to veto any of the appointments to the IGC. Members of the formerly exiled political parties ended up taking 18 of the positions on the IGC.4

In their negotiations with the CPA, the parties also demanded the right to pick the cabinet ministers for the first post-Baath government.5 In September 2003, the announcement of the new 25-member cabinet indicated that the parties at the core of the new elite pact had successfully secured control over the institutions and resources of the Iraqi state. As the ministers subsequently chosen by the IGC took up their new roles, the parties gained authority over the budgets and payrolls of the corresponding ministries.

Ideologically, this competition for control of the state by a group of formerly exiled politicians, empowered by the US force of arms, was justified through the claim that they represented the different ethnic and religious groups that made up Iraqi society.

Ideologically, this competition for control of the state by a group of formerly exiled politicians, empowered by the US force of arms, was justified through the claim that they represented the different ethnic and religious groups that made up Iraqi society. Two of the major parties, the KDP and the PUK, claimed to be the national representatives of Iraq’s Kurdish minority. Another two parties, SCIRI and the Islamic Dawa Party, argued that they represented the Shia majority of Iraq, while the Iraq Islamic Party claimed to represent the Sunni section of society. The parties used the muhasasa taifiya and the ethos of national unity to legitimize the division of state resources among themselves.

The first national election in January 2005 was contested by large electoral coalitions of parties claiming to represent different ethno-sectarian communities. The United Iraqi Alliance (UIA), which brought together the Shia Islamist parties, gained a plurality of the votes, winning 48.2 per cent, while the Kurdistan Alliance (KA) won 25 per cent. In spite of their coalition’s clear victory in that election, senior UIA figures Abdul Aziz Hakim, Ibrahim al-Jaafari and Nouri al-Maliki were all committed to ‘an inclusive solution’. This, they said, would build ‘harmony among all segments of the Iraqi people’.6

Fuad Maasum, the chief negotiator for the KA, set out how this inclusive solution would be reached: through extended negotiations until a bargain could be brokered on all aspects of government formation. Only when this general agreement had been achieved would the newly elected national assembly convene to give its formal blessing to what had been negotiated behind closed doors by political party bosses.7 This type of extended negotiation between the dominant political parties has shaped the formation of governments after every national election since 2005.

Once the dominant parties had established their elite pact, the next step was to ‘sectarianize’ the three most important offices of state. This involved dividing the roles of prime minister, president and parliamentary speaker between the dominant parties. In the name of Shia Arab majoritarianism, the UIA claimed the premiership, thought to have the greatest coordinating power within the government. The KA took the presidency. The position of speaker of parliament was allocated to political parties claiming to represent Iraqi Sunnis.8

Of greater importance, given the resources that the state commanded, was another agreement to allocate control of government ministries to political parties. Again this process, and its domination by the leading parties, was justified by the claim that sharing control of the state in this way was simply a means to recognize and work within the existing ethno-sectarian divisions in Iraqi society. Although the principle underpinning these allocations was not questioned in 2005, the negotiations produced acrimony over which parties should get control of which ministries, given the different levels of power and different-sized budgets associated with each ministry.

This commitment to muhasasa taifiya and the ethos of national unity not only justified the elite pact’s takeover of state power – it also provided ideological coherence and unity to the parties, along with a common agreement effectively legitimizing the pursuit of resource extraction and societal domination. The mistrust, tension and competition within the ruling elite were reflected by the considerable length of time it took after each national election to reach agreement over the formation of a new government. Since 2005, the entire negotiation process – from the national vote to actual government formation – has occurred six times (see below), taking an average of 138 days to complete.

The role of elections in enforcing elite dominance

Since 2003, Iraqi lawmakers have agreed and ratified various electoral laws and reforms. They moved away from a closed-list system in 2005, to a semi-closed list in 2010, to open lists in 2014, and to a first-past-the-post constituency system in 2021 (the latter following an electoral reform law passed by the Iraqi parliament). Despite the changes in electoral laws, the essential process of government formation and its dominance by the same political parties has remained consistent, guided by an ethno-sectarian division of power in the name of national unity.9

The parties that form the elite pact have built their long-term economic, political and coercive unity during successive government formation processes. As mentioned above, these negotiations have occurred after each national election: twice in 2005, then in 2010, 2014, 2018 and again in 2019–20 after Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi was forced to resign. Each time, the process has highlighted the critical role of elections in reinforcing the dominance of members of the elite pact. For example, although electoral turnout in Iraq has declined since 2005 and the ‘Shia bloc’ has fractured, Shia Islamist parties have retained their ability to gain a plurality of votes and seats in successive Iraqi parliaments.

In part, such outcomes reflect the fact that national elections in Iraq, whatever rules they are run under, not only empower competing political parties but also regulate that competition. Following the second national elections of December 2005, the UIA introduced a way to institutionalize the division of government ministries after each election, reducing the wrangling involved in the process.10 The allocation of ministerial control was to be determined according to a points system based on the number of seats each party in the elite pact had gained in the elections. This allowed parties to take the ‘points’ accrued through winning parliamentary seats and ‘spend’ them on securing control of the three main offices of state or access to ministries with different levels of power and financial worth. For example, two parliamentary seats were worth one point after the 2018 elections. The offices of prime minister, president and speaker of parliament each cost about 15 points to obtain. Cabinet posts were divided into sovereign ministries (interior, finance, oil, foreign affairs and defence) and service ministries, with the electricity and health ministries having the largest budgets. In 2018, it cost five electoral points for a party to obtain control of a sovereign ministry, and four to obtain control of a service ministry.11

The political system that the dominant parties have created is highly decentred. In 2005 each government minister, once appointed, owed loyalty not to the government, the prime minister or a cabinet minister, but to the party bosses who had selected him or her to run that ministry. And each prime minister, from Ibrahim al-Jaafari onwards, has struggled to impose any form of centralizing logic on this system. Nouri al-Maliki, the only prime minister to have served two terms (from 2006 to 2014), had the most success. However, his efforts also put the system as a whole under immense pressure by undermining the already weak coherence and independence of the senior civil service.

03 Rethinking corruption in Iraq

In the Iraqi context, corruption’s most pernicious effects arise from the penetration of vested interests throughout the machinery of state. Key problems include the politically driven expansion of public sector payrolls and widespread fraud in relation to government contracts.

How corruption has been understood

Corruption in Iraq is often understood as an individual crime motivated by personal greed and a propensity to break the law for self-enrichment.12 Most of those who have criticized or sought to campaign against corruption have focused on personal motivations for illicit wealth accumulation.

However, the political corruption that has been at the centre of the post-2003 political system has become far more consequential to the coherence of the state and its everyday functioning. This systemic corruption is carried out and sanctioned at an elite level. It involves a collective, not individual, decision to use unfair access to state resources for the benefit of the whole ruling class. According to Transparency International’s definition, political corruption is a ‘[m]anipulation of policies, institutions and rules of procedure in the allocation of resources and financing by political decision makers, who abuse their position to sustain their power, status and wealth’.13 Politically sanctioned corruption has bound Iraq’s post-2003 leadership together in a rough and ready unity.14

International actors bear their own responsibility for the growth and prevalence of such corruption after 2003. The CPA played a central role in setting up the framework in which politically sanctioned corruption was able to thrive. The ill-thought-out use of cash to fund reconstruction, the desire for quick results no matter what the longer-term consequences, and very poor accounting procedures drove a rapid increase in abuses of the system during this period.15 This is one of the myriad negative legacies left by the occupation authorities.

Systemic corruption is carried out and sanctioned at an elite level. It involves a collective, not individual, decision to use unfair access to state resources for the benefit of the whole ruling class.

Nearly two decades after the invasion and occupation, the overall extent of the resources taken out of the state’s coffers through politically sanctioned corruption is hard to estimate. Ahmed Chalabi estimated in 2014, while head of the finance committee in the Iraqi parliament, that the country had lost $551 billion from corruption during the two Maliki premierships.16 In the run-up to the 2018 national elections, Iraq’s Parliamentary Transparency Commission estimated that at least $320 billion in government funds had disappeared over the previous 15 years.17 Ali Allawi, at the end of his first term as finance minister (2005–06), estimated that corruption diverted between 25 and 30 per cent of the government’s budget to the ruling political parties. In 2020, in his second stint as finance minister, he estimated that between $100 billion and $300 billion was held overseas by Iraqis, noting that ‘the large majority of these assets are illegitimately acquired’.18 A senior official with responsibility for a major service industry has estimated that his ministry alone had lost $80 billion due to politically sanctioned corruption.19 However, for political reasons there has never been a forensic or transparent investigation into the exact financial costs of politically sanctioned corruption in Iraq.

These various estimates of the extent of government corruption were echoed in interviews conducted by the authors in Baghdad between 2018 and 2021. During a confidential interview, one senior official estimated from his own direct experience of running a ministry that as much as a quarter of that ministry’s budget was spent on tendering for fraudulent contracts. He then said that another quarter of the budget was wasted on payroll corruption in respect of political appointees, government employees who draw a regular wage but never turn up for work, and ‘ghost workers’ (fictitious persons on behalf of whom the political parties claim salary budgets).

Such theft certainly funds personal enrichment, tying members of the ruling elite together and creating a community of complicity and guilt. But it also funds party political operating budgets, providing parties with the money needed to build electoral constituencies and compete for power.20 The systemic nature of this corruption is indicated by the fact that major corruption scandals have, at different times, touched nearly every ministry in every administration since the formation of the IGC in 2003.

Public sector payroll expansion

A key by-product of this structural corruption has been a rapid expansion of the public sector payroll. From 2005 onwards, parties that performed well in elections went on to appoint ministers who would then control the budgets and payrolls of the corresponding ministries until the next election. Each party used this power to employ family, party members and followers.21 In a labour market dominated by civil service and military employment, with demand for jobs far exceeding supply, the easiest way to secure state employment was to join or pledge allegiance to one of the dominant political parties, or to bribe a lower-level functionary. This process drove the sustained expansion in government employment.

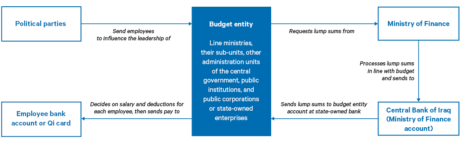

Figure 2. Flowchart of payment process for government employees

– For more on budget entities, see: Tabaqchali, A. (2021), ‘Gone with the Muhasasa: Iraq’s Static Budget Process, and the Loss of Financial Control’, Atlantic Council, www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/GONE_WITH_THE_MUHASASA-_IRAQS_STATIC_BUDGET_PROCESS_AND_THE_LOSS_OF_FINANCIAL_CONTROL.pdf.

Frank Gunter, a US academic, has estimated that in 2013 as many as 10–25 per cent of those listed as government employees were ‘ghosts’. And in 2020, Finance Minister Ali Allawi estimated that the number of employees on the government payroll had reached 4.5 million, of whom 300,000 were ghosts.22 This arrangement has allowed party-aligned officials to split the wages of ghost workers between themselves.23

Allawi’s predecessor as finance minister, Fuad Hussein, said in 2019 that the number of public sector employees and pensioners had increased from 850,000 in 2003 to 6.5 million in 2019.24 Employment-related corruption has led to an overstaffed bureaucracy in Iraq, as payroll expansion has allowed political parties to build patronage networks by offering public sector employment to members of their constituencies.

According to research conducted by the authors, government employment can also be gained through bribery – another channel through which political parties generate revenue. For instance, Alia Nusayif, a member of parliament from the State of Law coalition, complained that employment in the Ministry of Electricity could be obtained by paying a $5,000 bribe to officials.25 And one former member of parliament said that the cost of obtaining a job could be tens of thousands of dinars.

Contract fraud

An even more damaging by-product of the political parties’ control of ministries is the endemic contract fraud that occurs across all of government. According to Radhi Hamza Radhi al-Kinani, the head of the Commission of Integrity (2004–06), the misuse of government contracts was ‘… the father of all corruption issues’.26 Typically, ministry contracts are awarded to businesspeople who are close to the dominant political parties or to their proxies in government ministries. Costs are then deliberately inflated, with the profits divided between the contractors and the parties.27 Complaints about exorbitant prices and poor or non-existent delivery of public services and projects are ignored, as the same senior politicians and civil servants who oversee the awarding of contracts ensure that ministerial-level investigations into non-delivery are not pursued.28

A central part of governmental contract fraud includes the use of fraudulent shell companies. One of the biggest scandals in the electricity sector in Iraq concerned a contract between the Ministry of Electricity and a supposedly British company, ‘Power Engines’,29 to build a power station in the city of Nasiriya in southern Iraq. The Iraqi government paid the contracted amount of $21 million only to find that the company was a fake.30 Yet the government did not sack or punish those involved in drawing up the contract or file a lawsuit. Another official document revealed the loss of $8 million from the General Directorate for North Energy Production, again to fake companies.31 In yet another scandal, a network involving the use of counterfeit smart cards with a value of 1.5 billion dinars (the equivalent of around $1 million at today’s exchange rate)32 was discovered in the Finance Ministry in 2017.33

Iraq’s oil wealth and centralized economy have made it susceptible to corruption and personal wealth accumulation. For instance, from 2004 to 2009, the Ministry of Oil lost almost $1.5 billion due to overpricing and undersupply. In another example, a member of the Iraqi parliament, Talal al-Zobaie, said in 2013: ‘The amount of payments of the losses incurred by the Ministry of Electricity between 2003 and 2011 as a result of oil theft by oil companies contracting with the ministry is estimated at $200 million per month.’34 Similarly, corruption in electricity generation and distribution is estimated to have resulted in losses of $4–6 billion between 2003 and 2020, mainly through padded contracts and purchases of overpriced and/or inappropriate equipment.35

The above episodes further illustrate the central argument of this paper, which is that the typical understanding of corruption in Iraq – as driven by personal or group enrichment – ignores the larger political dynamics that lie at the root of such problems. Moreover, it is important to consider how the post-2003 political parties have used their control of government ministries to fund their own operations and dominance of society. In this sense, corruption’s primary role is to deliver state resources to participants in the elite pact, thereby providing (albeit, at a high public cost) a measure of political cohesion while enabling the funding of party organizations.

04 The expansion of the special grades scheme

A key way in which political parties in Iraq secure and entrench their power is through the appointment of loyalists and proxies to ‘special grades’ positions in the civil service.

The sheer number of contracts signed by each government ministry every week means individual ministers cannot keep track of, let alone direct, how each contract is drafted, tendered and paid.36 Contract fraud underpins most government corruption, and provides the resources to fund the ruling political parties and maintain the cohesion of the elite pact. Yet this pervasive system of fraud remains understudied. Although it stands at the centre of corruption and power in Iraq, very few articles or reports have been written on the role of senior civil servants in the special grades scheme, or of those who act under temporary employment contracts (known as wikala) or temporary authorization (known as takleef).

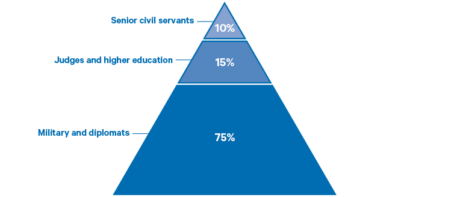

The legal purpose of the special grades is to allow for a higher salary band for distinguished civil servants. The special grades account for some 5,000 government officials in total. Most of these positions are diplomatic (ambassadors) or are held by senior military ranks in the Iraqi security forces.

At the same time, across the Iraqi government almost 1,000 special grades are senior civil servants who act as direct proxies for political parties. They occupy positions such as director general, deputy minister, head of a state-owned enterprise, or chief of staff in a ministry or government agency. These individuals are directly responsible for government contracting. In addition to allowing certain civil servants, as mentioned, to earn higher pay than in the standard civil service salary bands, the special grades system facilitates the diversion of resources from contract-related corruption to political parties.

Figure 3. Pyramid diagram of all special grades

– Source: Compiled by the authors.

The power of special grades employees comes not only from their official roles in ministries, but also, critically, from the political protection they receive from their patrons. This combination of top-level cover and influence is particularly useful when civil servants in the special grades clash with ministers.

Over the years, the special grades system has evolved. It has withstood and overcome challenges including elite contestation, intra-party hostility, political fragmentation and popular uprisings calling for reform. In 2016, the discourse of government formation changed when the major parties agreed to appoint ‘independent’ technocratic ministers. To some extent, this agreement has remained in place since then. However, it has actually enhanced the power of the special grades, as some of their number have taken up roles as the ‘technocratic’ ministers running the very ministries that had previously employed them. Even the 2019 October Uprising, which ended Adel Abdul Mahdi’s premiership, did not undermine the inner workings of the special grades system. Understanding the evolution of the system is essential to any discussion of how to reform the Iraqi state.

2006–10: Setting up the special grades system

The political use of the special grades system has its roots in the turmoil that followed the regime change after the fall of Saddam Hussein. Politicians returning from long exile believed that they faced a civil service that had been deeply politicized by 35 years of Baathist rule. Their first move to tackle this problem was the de-Baathification of Iraq’s civil service. This involved purging from government employment anyone who had previously been appointed to the top four levels of the Baath Party, and also banning former party members from the three top levels of civil service management. In the first four weeks after the US-led invasion of 2003, 41,324 state employees were sacked. This root-and-branch purge not only removed the institutional legacies and knowledge of state function in all government agencies, but it also allowed Iraq’s newly empowered political parties to insert their cadres at the top of state institutions. However, in these early years immediately following the invasion, the process was haphazard and ad hoc.37

The politicization of the civil service became more organized during Nouri al-Maliki’s first premiership, from 2006 to 2010. All major political parties were attempting to place their followers in civil service positions. However, to increase his own power, bolster the coherence of the government and reduce his reliance on the dominant political parties, Maliki systematized this process. He reached back into pre-2003 legislation and found a 1966 law that legalized the use of special grades and the short-term appointment of senior civil servants in the Iraqi bureaucracy.38 This law gave the prime minister the legal cover he needed to appoint higher-paid loyalists in each government ministry and across the civil service.39 In an attempt to sidestep fractious ministerial debates in the cabinet, Maliki set about placing special grades appointees loyal to him in ministries whose coherence was threatened by walkouts and boycotts by the parties, some of which sought the collapse of his government.40 Maliki effectively created a network of loyal senior civil servants at the top of ministries, centralizing a degree of power in his own hands.41

One of Maliki’s key steps in building his network was to create space for his own appointments. He began to target senior civil servants who had been haphazardly appointed under the CPA and the successor transitional governments (from 2003 to 2005), taking advice from lawyers such as Tariq Harb. In a later online post, Harb defended the move, arguing that any special grades appointed either by the CPA or by the interim and transitional governments had lacked the approval (from the Council of Ministers or the Council of Representatives) which they needed to be legal.42 Using this legal interpretation, Maliki justified the removal of old special grades personnel because they had not been approved by the newly appointed Council of Representatives.

However, this procedural expedient was not enough on its own to consolidate Maliki’s hold on state power. So he also sought other channels through which to remove non-loyal special grades personnel. Renewing de-Baathification became an essential tool in this quest. To this end, he pushed the enactment of the 2008 Law of the Supreme National Authority for Accountability and Justice, Article 6 of which authorized the removal of all members occupying special grades positions prior to 9 April 2003.43

Maliki also relied on military successes to empower his moves against non-loyal civil servants. For instance, he used the March 2008 Charge of Knights campaign in Basra to remove special grades personnel whom he deemed problematic. In May, shortly after the campaign, he removed Jabbar al-Luabi from his position as director of the South Oil Company. At the time, a cable from the US embassy’s office in Basra argued the following:

Many believe … that Jabbar’s dismissal is politically motivated. PM Maliki has used the success of the Charge of Knights operation to make sweeping personnel changes in the south. While many of the changes were necessary, some Baswaris [sic] believe that the GOI [Government of Iraq] is being opportunistic.44

By the end of his first term in office, Maliki had successfully removed a number of special grades civil servants and had begun populating these positions with his own loyalists. Crucially, the cabinet allowed him to make such appointments during this period because many of the political parties were still focused on the elite level of government and were less aware of the significance of civil servant nominations. The Sadrists, however, were aware of the importance of the special grades and began competing with Maliki. Other parties, however, did not have enough information on how the different institutions of the state worked together to fully appreciate and hence block what Maliki was hoping to achieve.

By the end of his first term in office, Maliki had successfully removed a number of special grades civil servants and had begun populating these positions with his own loyalists.

At the beginning of his first prime ministerial term in 2006, Maliki had been perceived as a weak, compromise candidate with no militia to support him. In response, he sought to use civilian state institutions – especially the special grades – to acquire and maintain power, projecting his influence on to government ministries weakened by a series of party political boycotts of the cabinet. Controlling and then expanding the special grades scheme gave Maliki increasing power across the various institutions of the Iraqi state, and allowed him to harvest information from and coordinate between different senior civil servants.

For the first two years of his premiership, however, the balance of power within the state did not move decisively in his favour. The ruling political parties continued to control the majority of ministries, having appointed senior party members as ministers. At this point, they retained the political influence to overrule the special grades civil servants whom Maliki had appointed.

Notwithstanding these struggles, this period marked the start of the systematic use of the special grades to politicize the senior ranks of the civil service. In particular, Maliki incrementally increased the number of special grades personnel placed in ministries, as he attempted to minimize the challenge that the major political parties posed to his continuation in power.

2010–15: Pluralization of the system and the use of wikala

By the time of the national parliamentary elections of 2010, amid a sharp reduction in politically motivated violence, Iraq’s ruling elite had managed to achieve a degree of cohesion between the leaderships of the various political parties. Yet the 2010 election campaign and subsequent negotiations on the formation of a new government presented two new challenges to the entire political system.

The first challenge arose from the election victory of Iyad Allawi’s Iraqiyya coalition, which won 91 parliamentary seats. This compared with 89 seats for the Maliki-led State of Law coalition and 70 for the Iraqi National Alliance.45 Iraqiyya had fought the election on an overtly secular nationalist platform, winning seats in the south and across central Iraq. This posed a direct challenge to the ethno-sectarian ideological justification underpinning Iraq’s political system at that time.

The second challenge came from the power that Maliki had amassed primarily through his expanding control of the formal bureaucracy and special grades. The prime minister was increasingly using the special grades to overcome the fractured, decentred dynamics that had previously rendered the cabinet incoherent as a governing body, complicating coordination between ministries. The increased coherence of Maliki’s power – obtained partly through his use of special grades – challenged the primacy of the very parties that had created and benefited from the political system.

After 249 days of government formation negotiations, a compromise was eventually hammered out in November 2010. As the price for retaining the premiership, Maliki was forced to sign a nine-part agreement designed to place meaningful constraints on his power.46

Part six of this intra-elite deal, known as the Erbil Agreement, retained but pluralized the special grades scheme, opening it up more than before to all of the political parties in the ruling elite. A committee was set up under the joint management of the prime minister, the president and the speaker of parliament. Between 2010 and 2015, this National Balance Committee was meant to oversee the distribution of special grades appointments across all parties in government, thus making the senior ranks of the civil service subject to the ethos of national unity.47 Yet most of the negotiations remained behind closed doors. The number of general special grades appointments across the Iraqi state grew from 2,962 in 2006 to 5,308 in 2019, and hundreds of positions were politicized. As prime minister, Maliki himself is estimated to have been responsible for 35 per cent of all special grades appointments.48

At the same time, the pluralization of the system meant that Maliki could no longer appoint people to special grades positions purely on his own initiative. Instead, he was forced to work with the National Balance Committee to attain parliamentary approval for each appointment. To overcome this bureaucratic hurdle, he looked for another legal loophole and found wikala – a scheme for temporary contract appointments.49 Wikala contracts gave Maliki the ability to appoint his own special grades candidates on an acting, short-term basis that could be extended without parliamentary approval. In most cases, these loyalists remained in their positions even after their wikala contracts had technically expired. Eventually, wikala contracts would also make it easier to remove incumbent senior civil servants as political parties competed after each election.

The pluralization of the system meant that Maliki could no longer appoint people to special grades positions purely on his own initiative. Instead, he was forced to work with the National Balance Committee to attain parliamentary approval for each appointment.

After the 2010 Erbil Agreement and the creation of the National Balance Committee, a larger number of political parties began using special grades appointments, which they now controlled directly, to gain power within different institutions of the Iraqi state. The major political parties now knew the power that these appointments could wield. As a result, following the 2014 elections, party-aligned special grades appointments became an explicit part of the government formation negotiations, alongside ministerial appointments. Under the points-based system guiding the negotiations on government formation after each election, parties could now choose whether it was to their advantage to pick ministers, senior civil servants or a mixture of the two.50

2016–20: Taking the system ‘underground’ in the age of technocrats

The mass protests that erupted in the summer of 2015 and continued into the spring of 2016 called for the appointment of technocratic ministers as a means of ending endemic corruption and limiting the domination of the state by the main political parties. In urban squares occupied by the protesters, a common slogan equated corrupt politicians (al-fasideen) with terrorists/members of ISIS, the latter of which at the time controlled up to one-third of the country. The protesters were struggling to find jobs due to a sluggish Iraqi economy, impacted by the 2014 oil price crash. They pointed to corruption, which they argued enriched the ruling parties and left little or no state resources to trickle down to ordinary citizens.

In their call for change, protest leaders – both from the Sadrist trend and the different civic trend groups – argued that technocratic ministers could be used to tackle corruption by challenging the politicization of ministries that had become so prevalent. The protest movement’s goal was to hold to account and weaken the post-2003 political parties by removing their access to power – access hitherto overtly achieved through their appointment of ministers to each government of national unity.

In response to these demands, the prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, agreed to change several of his ministers, and brought in technocrats with experience in the specific areas covered by the ministries in question. However, this move failed to depoliticize the Iraqi state. Instead, it consolidated the special grades system, which became even more important for the exercise of party political influence by empowering special grades appointees over weak technocratic ministers. As a consequence, ministers complained that their signatures on government contracts became mere ‘rubber stamps’ – formal authorization of decisions made elsewhere, beyond their control.

This shift in power within the Iraqi state was exemplified in the 2018 elections, in which the major competition between political parties was no longer for the overt appointment of cabinet ministers but rather for the covert allocation of special grades. As one Iraqi analyst argued after the elections of 2018:

Special grades are one of the most important files that attract the eyes of politicians and parties, given that these important positions are the nerve of all institutions and state ministries, and thus muhasasa.51

Negotiations during the subsequent government formation process revolved around 500 to 700 special grades positions. Interviews carried out in Baghdad by the authors suggest that the Sadrists – who had won the largest share of the vote in the 2018 election – received the largest share of special grades appointments, numbering 200. They did not take any ministerial posts but gave their blessing to the appointment of weak independent ministers while focusing on access to the special grades. To ensure that their candidates were passed by the Council of Ministers, they focused on gaining control of the Secretary of the Council of Ministers (COMSEC), which oversaw decision-making on civil service appointments.52 All the other victorious parties took their own share of special grades positions, thus also placing loyalists in the senior ranks of the civil service across the state. After their installation, these party-aligned officials would be key players in government contracting in each ministry, siphoning off money to the respective parties to which they owed allegiance.

The role of special grades within the state has now become a major issue in Iraqi politics. By 2018 it had become a main topic in discussions about corruption.53 The Iraqi parliament debated the merits of temporary contracts (wikala) on several occasions, as parties outside the system sought to gain greater influence.54 In his talk to Chatham House’s Iraq Initiative in February 2019, Parliamentary Speaker Mohammad al-Halbousi argued that one of the key obstacles in tackling corruption was wikala-related corruption (fasad bil-wikala).55 In a parliamentary debate, a Fateh legislator, Ahmad al-Assadi, complained that his coalition was struggling to obtain special grades for itself.56

The independent technocratic ministers appointed in response to the 2015–16 protests were unable to control their own civil servants and hence their ministries.

As illustrated above, the exercise of party political power in Iraq had thus moved from the level of minister to one level underneath, that of senior civil servant. The independent technocratic ministers appointed in response to the 2015–16 protests were unable to control their own civil servants and hence their ministries. The political parties subsequently shifted their focus from appointing their own people as ministers to making sure that they got as many special grades appointees as possible across all ministries.

2020 to present: Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s government and the promotion of special grades

The Adel Abdul Mahdi premiership, which began in October 2018, lasted only one year. From October 2019, mass demonstrations swept the country and removed what legitimacy the cabinet had gained from the previous year’s elections. Abdul Mahdi was forced to step down. After seven months of inconclusive negotiations, Mustafa al-Kadhimi became prime minister in May 2020. Kadhimi came to power promising the wide-ranging and sustainable political and economic reforms that the demonstrators had demanded. Media reports surrounding the appointment of Kadhimi’s cabinet stressed the high proportion of technocratic ministers it contained. This initially prompted suggestions that the new government might have achieved a higher level of autonomy from Iraq’s dominant political parties than any of its predecessors.

However, the composition of Kadhimi’s cabinet did not mark a major departure from the practice of previous governments. Instead, it indicated a further increase in the power of party-aligned special grades. Unlike the technocrats appointed to the cabinets under Abadi and Abdul Mahdi, a number of Kadhimi’s ministers were former senior civil servants from the very ministries which they had been appointed to lead. Apart from a couple of independent technocrats, the great majority of the new cabinet’s members were either ministers who had served their political patrons as senior civil servants in the same ministries or officials who had made agreements with political parties to gain their positions.57

In spite of championing a reform agenda, Kadhimi has no more power to enact reforms than any of his predecessors did, and the prime minister remains constrained by the existing political system.

An episode involving a well-known Iraqi poet, Faris Harram, shed some light on the Kadhimi government’s process of formation. Kadhimi had asked Harram to become minister of culture, but as Harram went through the nomination process, the political party controlling the relevant ministry told Harram that his appointment would not be approved unless he met that party’s conditions. Ultimately, Harram could not agree to allowing the party to control his ministry, and as such he withdrew from the nomination process.58

Given this background, Kadhimi’s current cabinet – and hence the functioning of his government today – cannot be said to represent a break with Iraq’s post-2003 political system. Instead, the cabinet’s composition displays evidence of further politicization of the Iraqi state. Long-standing party-aligned civil servants, who have for years been serving party interests in ministries, have now been appointed to actually run those ministries. They can be expected to maintain the close relationships with the parties that have protected and promoted them over many years.

In short, in spite of championing a reform agenda, Kadhimi has no more power to enact reforms than any of his predecessors did, and the prime minister remains constrained by the existing political system.

05 The consequences of power: politically sanctioned corruption

Efforts to address corruption must begin by comprehensively mapping the dynamics of power in Iraq – identifying not only political parties’ penetration of government ministries but also their privileged access to ‘special grades’ positions in the civil service.

The special grades scheme has become a way of corruptly channelling resources to each political party in proportion to the amount of power won at each election. The resources thus distributed vary according to each party’s ability to win seats, with the number of seats often translating into civil service appointments. Since the creation of the Iraqi Governing Council in 2003, the country has held five national elections and formed six governments of national unity. However, the evolution of the political system during this time has not reduced the grip of the dominant parties. On the contrary, the influence of party political interests over the appointment of senior civil servants has increased. This in turn has driven politicization deeper into the institutions of the Iraqi state.

Iraq has experienced considerable changes since 2003, including cycles of civil war and violent conflict, the introduction of various electoral reforms and electoral systems, the splintering of political parties, the resignation of a prime minister, and popular uprisings. Despite all these events and changes, the essential system of political corruption that underlies the elite pact has remained unchallenged. If anything, as politics in Iraq has become more fragmented (due to the proliferation of political parties, elite infighting, and protests in 2019 calling for the end of the post-2003 settlement), the politicization of state institutions has continued apace. As a result, the power of the parties over the institutions of the state has become stronger.

This system has so far proven itself capable of sidestepping reform efforts. Even pressure from the 2019 demonstrations, the largest and most sustained since 2003, failed to bring about sustainable reforms. The system’s complexity – along with the non-transparent role that special grades play in it – makes it a difficult entity to map, understand and hence reform.

Iraq has experienced considerable changes since 2003, including cycles of civil war and violent conflict, the introduction of various electoral reforms and electoral systems, the splintering of political parties, the resignation of a prime minister, and popular uprisings.

Economic pressures are adding to the reform challenges. In the last year, fluctuations in global oil prices and the influence of COVID-19 are estimated to have reduced the size of Iraq’s economy by 10 per cent, driving the government into an extended balance-of-payments crisis. As of mid-2020, government revenue was running at 3 trillion dinars (at the time, roughly $2.5 billion) a month, compared with monthly expenditure of 7 trillion dinars ($5.8 billion).59 This economic crisis has become the dominant issue for Kadhimi’s government. In a series of interviews with Iraqi and international media, Ali Allawi, the deputy prime minister and finance minister, made it clear that Iraq was in a dire economic situation; he warned of ‘severe security consequences’ if the economy was not ‘restructured radically’.60 He also made it clear that one of his first targets for reform would be the state pensions and payroll. However, a first attempt at imposing fairly minor pension reforms in June 2020 was greeted with outrage in Iraqi society and in parliament, forcing a quick government retreat.61 This episode highlighted the government’s vulnerability to concerted political pressure from both the elite and wider society.

In the face of low oil prices in 2020 and youth-driven social unrest, both Allawi and Kadhimi argued for radical reform and opening of the economy. However, they have continued to face opposition to any such initiative from within the ruling elite, whose members have relied on the expansion of the public payroll to bolster their political support. In 2020, Allawi and his team of reformers published a white paper that mapped out his strategy for reform and sought to justify his proposal for further domestic and international borrowing to get through the crisis. However, the white paper, like a number of previous Iraqi government strategies, was more a statement of intent than a realistic strategy for achieving meaningful reform. It was based on the assertion that the economic situation was so dire that Iraq’s ruling elite had no choice but to welcome far-reaching economic reforms. The white paper’s negative reception in parliament showed how Allawi and his team were operating according to a different logic from that of the rest of the ruling elite. The latter’s political logic, which has shaped the entire political system to date, is to continue to try to extract as much money as possible from the Iraqi state, even in times of economic crisis.

In all likelihood, the ongoing clash between Allawi’s economic agenda and the elite’s political agenda will not result in reform. The Iraqi state will continue to borrow heavily, while doing little or nothing to tackle the structural problems that have dogged every post-2003 government. Allawi’s white paper set out plans for sustained cuts to government payrolls, pensions and other benefits. It also outlined an ambition to solidify and systematize Kadhimi’s attempts at tackling corruption and making the economy more attractive to foreign investment. Given the structural constraints the government faces, it is highly doubtful that the policy solutions proposed in the white paper will ever get implemented.

Concluding remarks and recommendations

In February 2019, the authors of this paper sat in the office of a senior foreign diplomat in Baghdad. After the typical diplomatic niceties, the envoy erupted into a rare and detailed monologue, born of his frustration. He had for many months worked on securing a contract in Iraq for a major company from his country. He had gone back and forth with the relevant Iraqi minister. Eventually, they had agreed on the commercial terms of the deal, and the diplomat had informed his own government of the success. Then, overnight, the agreement fell apart. He was dumbfounded. How could the Iraqi minister in question ignore the economic logic that shaped the diplomat’s understanding of the world, or jeopardize the mutual gains that the deal would deliver? The contract would supply much-needed government services, at a good price, to the Iraqi population. However, for reasons the foreign diplomat could not fathom, the Iraqi government had rejected it.

Over the course of the conversation, the authors outlined the political logic underpinning the special grades system, of which the diplomat was unaware. After explaining the system, the authors asked the diplomat if his team had mapped positions within the relevant ministry to understand how the political parties controlled the senior civil servants with whom he was negotiating? The diplomat had not done this research. His assumption was that an apparently economically logical and mutually advantageous agreement reached with the minister was sufficient to push the deal forward. In other words, he had fundamentally misread the logic of power and politics that operates at sub-ministerial level in an Iraqi government ministry.

Months later, the authors met with the diplomat again, who was obviously in a much better mood. He had just informed government colleagues in his capital that the deal with the company had finally gone through. It had progressed because he had identified the chokepoint in the system: a particular civil servant who had been acting on behalf of a political party but against his own technocratic minister and the interests of the Iraqi population.

The story of the problems encountered by this diplomat demonstrates the wider barriers to political and economic reform in Iraq. These barriers are present for the Iraqi people, foreign diplomats, international businesspeople based in Baghdad, and indeed for reformers in the government of Mustafa al-Kadhimi. Rather than seeking to understand Iraqi politics and the state in terms of hierarchical, institutional, legal and rational models, this paper has argued that efforts by international policymakers to support reform are futile without a fundamental understanding of the dynamics of power across the whole Iraqi system. To achieve this, policymakers need to map not only the positions and formal power relationships of the ministers and government leaders with whom they deal on a day-to-day basis, but also those of the senior civil servants who run the institutions of the Iraqi state. Understanding, for example, which political party a director general in a ministry is aligned to could determine the success of a particular initiative. Such understanding also offers insights when development and reform policies promoted by the international community and applied in Baghdad and Erbil fail to achieve the goals set out for them.

Having mapped the political system as indicated above, those seeking to promote reform need to ensure that accountability is established at the special grades level. The two principal institutions in Iraq charged with combating corruption are the Board of Supreme Audit and the Commission on Integrity. Although the two bodies also suffer from politicization themselves, both have roles to play in improving government transparency and accountability – for example by investigating corruption at the special grades level and identifying which appointees act with political impunity.

The process should begin with a review of all wikala and takleef appointment contracts, to see which ‘temporary’ officials are still employed and which are in positions that have not received cabinet approval. Critically, an independent investigative body should track the work of the special grades across the whole of the state to ensure that these positions fall under the rules of each ministry and that their holders operate within a civil service code. Any wholesale attempt to depoliticize the civil service would be a mammoth undertaking and in all probability politically unrealizable. The key aim in any attempt to reform the political system in Iraq, therefore, should be to bring accountability to the senior ranks of the civil service. If the appointment and actions of these officials are not subjected to extended scrutiny, then any attempt to reform the wider system will be destined to fail.

About the authors

Toby Dodge is an associate fellow with the Middle East and North Africa Programme at Chatham House. He is also a professor of international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is the author of numerous papers and books about Iraq, including Iraq: from war to a new authoritarianism (Routledge, 2012) and Inventing Iraq: the failure of nation building and a history denied (Columbia University Press and Hurst & Co., 2003).

Renad Mansour is a senior research fellow and the project director of the Iraq Initiative at Chatham House. He is also a senior research fellow at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani, and a research fellow at the Cambridge Security Initiative based at Cambridge University. Renad was previously a lecturer at the London School of Economics and Political Science, where he taught the international relations of the Middle East. From 2013, he held positions as lecturer of international studies and supervisor at the Faculty of Politics, also at Cambridge University. He is the co-author of Once Upon a Time in Iraq, published by BBC Books/Penguin (2020) to accompany the critically acclaimed BBC series.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the Iraqis who were interviewed for this project. We also thank the peer reviewers who gave their comments. We would like to thank Georgia Cooke for managing this paper, Taif Alkhudary for providing research assistance, and Sandra Sfeir for providing research and logistical support for the authors’ many research trips to Iraq. Thanks also to Nicole El Khawaja for reviewing this paper and Jake Statham for editing the text.

The authors would like to offer their heartfelt thanks to the late Hisham al-Hashimi for all his help, support and advice during the research for this paper. It is to Hisham and his deep commitment to a better future for all Iraqis, for which he worked so hard, that this paper is dedicated.

Iraq Initiative at Chatham House

The project tackles the root causes of state fragmentation in Iraq, and challenges assumptions in Western capitals about stabilization and peacebuilding. The aim is to reach a more nuanced approach to navigating Iraq’s complex and interlinked political, security and economic environments.

The initiative is based on original analysis and close engagement with a network of researchers and institutions inside Iraq. At the local level, it maps key political, business, military and societal figures across Iraq. At the national level, it explores the struggle over the state.

The project uses these field-based insights to inform international policy towards Iraq. Chatham House convenes Iraq Initiative activities in various cities in the Middle East, the UK, the US and Europe.

Source: Chatham House. 17 June 2021

Comment here