(Bloomberg) — Explore what’s moving the global economy in the new season of the Stephanomics podcast. Subscribe via Pocket Cast or iTunes.

Iraqis were enjoying an unusually peaceful period. Baghdad appeared vibrant and safe in mid-September, with violence at its lowest since the 2003 U.S.-led invasion, having plummeted following a victory over Islamic State two years ago. Then something cracked. Massive anti-government protests erupted and drew an unexpectedly harsh response from authorities. The oil-rich country is now mired in the kind of unrest it had hoped was in the past, with officially at least 100 people killed and thousands wounded. So what went wrong?

What are Iraqis protesting about?

The demonstrations against corruption, a lack of basic services and unemployment started out small in Baghdad and southern cities on Oct. 1. But after security forces responded with tear gas and bullets, they spread and grew violent. Government offices have been stormed and the airport road cut off. Authorities tried imposing a curfew and a near-total internet shutdown to restore order but that only inflamed tensions. Human rights groups believe the death toll could be higher than the government figures, which don’t give separate counts for civilians or members of the security forces.

How bad is the economy?

Defeating Islamic State and a partial recovery in oil prices and production led to a recovery in growth. Iraq’s currently the second-largest producer in OPEC and the fifth-biggest in the world. At the same time, public services remain poor and 25% of younger Iraqis are unemployed. There’s been little progress in rebuilding infrastructure battered by conflict and about 1.8 million internally displaced people are in need of housing. The World Bank estimates the cost of reconstruction in the seven provinces affected by the war with Islamic State at $90 billion over five years.

What must the government prioritize?

Iraq will need to root out corruption, one of the main reasons for the failure to deliver public services. The nation’s among the most corrupt in the World Bank’s Control of Corruption Index. It also ranked 168 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index in 2018. Protesters say the political system set up after the 2003 invasion, which is based on ethic and sectarian quotas, rather than merit, lends itself to graft and means positions aren’t filed on merit.

What are authorities doing?

After tactics to restore order during the first week of demonstrations failed, authorities tried reaching out to protesters. President Barham Salih called for dialogue, while the military admitted to using what it called “excessive force.” Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi, who took office only last year, ordered the army to withdraw from Sadr City and put the police back in charge of security there. The neighborhood lies in Baghdad’s east, where 8 million people live in relative poverty and where the most serious clashes have taken place. The prime minister also issued a 17-point plan that includes creating jobs and stipends for the unemployed.

How does Iran fit in?

Some demonstrators have been carrying posters bearing the image of Abdul-Wahab Al-Saadi, a popular counter-terrorism chief whose demotion late last month has been blamed by his supporters on Iranian-backed politicians in Iraq. Iran has had an outsized influence in neighboring Iraq ever since its Shiite Muslim majority took a major role in governing following the U.S. overthrow of Saddam Hussein, a Sunni.

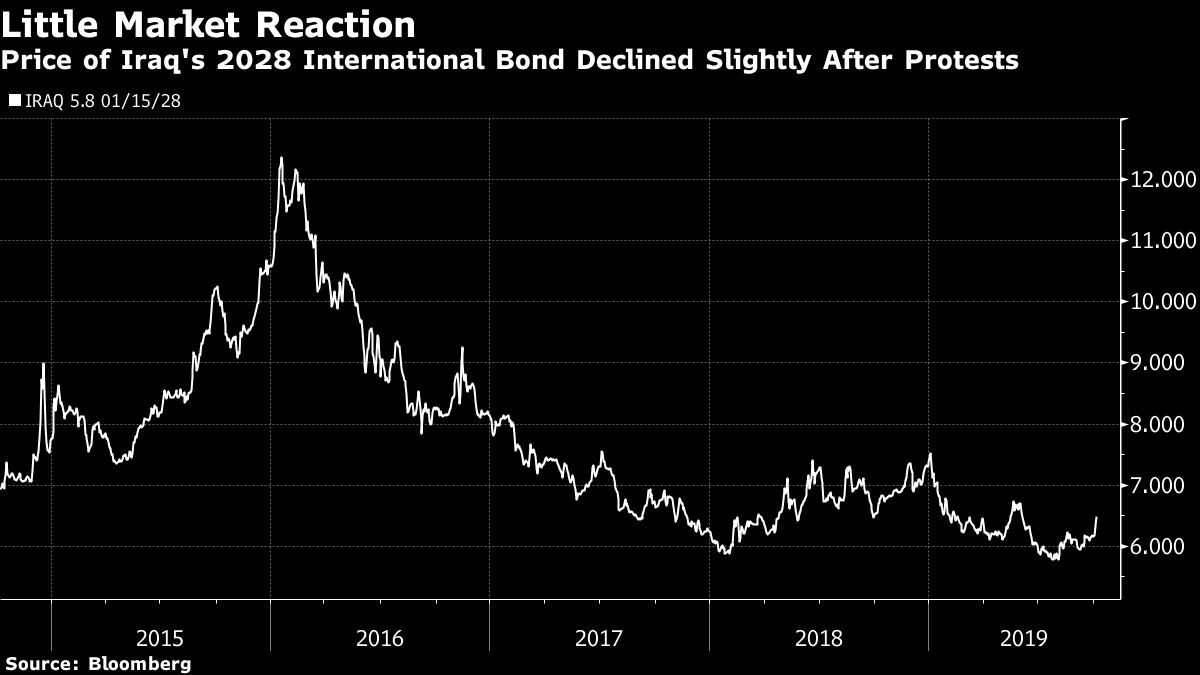

How have markets reacted?

So far, financial markets have taken the protests in their stride. Oil prices have actually declined, with investors more concerned about weaker global demand than supply disruption from Iraq. The country’s CDS spreads have risen only slightly and the yield on its 2028 Eurobond has barely moved in the context of a five-year chart. One reason for this muted market reaction is the fact protests have yet to reach oil production or export facilities. Iraq has also seen bouts of social unrest in recent years which didn’t impact the workings of government or oil flows.

What’s likely to happen next?

Iraqis have been voicing their grievances for years, but usually in the summer when temperatures soar and services falter. The timing and scale of these protests appears to have taken the government by surprise. Abdul Mahdi came to power promising a solution to corruption and the divide between rich and power but overhauling the system is hard. His position weakened after Muqtada al-Sadr, the populist Shiite cleric whose bloc is the biggest in parliament, called for his resignation and fresh elections. The protesters have no leader and there’s no one to negotiate with. Analysts warn the brutality of this wave of unrest could mark a dangerous turning point.

Source: Bloomberg•October 8, 2019

Comment here