One of the country’s most strategic provinces is up for grabs, but Baghdad and the KRG are too politically and economically broken to reach out and help.

Iraq’s Kirkuk province has long been identified as a fulcrum for political and ethnic tensions, with the potential to make or break national reconciliation efforts between Kurds, Arabs and Turkmen. With each passing week, Kirkuk rises on the agenda of Iraqi politicians, and the province is becoming a focal point for Arab-Kurdish and intra-Kurdish politicking.

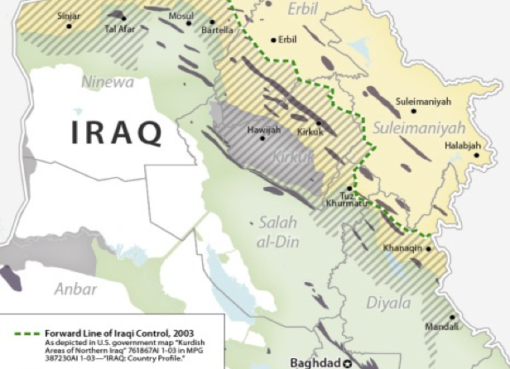

Kirkuk is currently central to five interlocking sets of conflicts. The first is the fight against the self-styled Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) group, which is slowing down in central Iraq and which has been largely static along the Kurdish-ISIL front line for many months. The US-led coalition now needs to generate a new northern front against ISIL that fuses together Sunni Arab paramilitaries with Kurdish and international support. Kirkuk is the launchpad for operations against the adjacent ISIL redoubt in Hawija.

ADMINISTRATIVE DEBATES

The second conflict coming to a head in Kirkuk is the debate between the federal government in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) over oil sales. Currently, the KRG is utilising around 180,000-240,000 barrels a day of oil extracted from fields in Kirkuk that were operated by the federal Northern Oil Company (NOC) until June 2014.

These volumes are critical to the Kurdish region’s new effort at economic independence from Baghdad. At the same time, NOC is still operating other Kirkuk fields that send around 170,000 barrels a day to Turkey for the federal government to export via the KRG pipeline. Collaborative export of these NOC-administered volumes may be an important part of cash-strapped Iraq’s budget in 2016.

Kirkuk is also the cockpit of administrative decentralisation debates between the federal government and Kirkuk province under its dynamic governor, Najmaldin Karim. Kirkuk probably has the most assertive local government in Iraq, with Karim striving to limit and balance the involvement of federal and KRG agencies in local affairs.

In recent months Karim and the provincial council have pushed back on Baghdad’s appointment of a new dean for the University of Kirkuk and a new head of the NOC, while Baghdad is trying to prevent the governor from removing the Kirkuk head of intelligence from the federal Interior Ministry.

DISSENT WITH BAGHDAD

Fiscal decentralisation of Kirkuk is another point of dissent between Baghdad and the province. Kirkuk is owed over $1.37bn in 2014 and 2015 regional development funds and “petrodollar” royalties that the Iraqi federal government budgets for oil-producing provinces. Of that amount, the province has only received $197m in the last two years. In the first half of 2015, only $12m has arrived to support projects in a province with 1.5 million inhabitants and a staggering 600,000 displaced persons.

But the KRG hasn’t stepped up: Kirkuk has not been paid “petrodollars” by the KRG on any Kirkuk oil that it exported — either with Kirkuk’s approval or without. Both Baghdad and the KRG defaulted on their supplies of fuel and electricity to Kirkuk, a province that often falls between the cracks of federal-KRG tensions.

The controversial subject of KRG independence could represent a fifth and final conflict in which Kirkuk will play a critical role. In the midst of the Kurdish region’s crisis over presidential powers, the main Kurdish parties disagree over what role Kirkuk might play in future voting and referendums: Should Kurds from Kirkuk vote in KRG presidential elections, potentially benefitting the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)? When should Kirkuk be asked if it wants to accede to the KRG — again, potentially tipping the balance towards the PUK and away from the Kurdistan Democratic Party? Or would a narrow referendum result to join the KRG inflame ethnic tensions in Kirkuk for decades to come?

The key trend visible is that outsiders use Kirkuk for their own benefits, but the devastating results are felt most deeply by the Kirkukis. For instance, the province’s lack of money has meant that over 5,700 much-needed new jobs created by the governor’s office have been suspended because salaries are unavailable.

One of the signature successes of the governorate, a local job-creation programme, is being starved to death because tiny increments of money, around $2m a month, are withheld by Baghdad for no apparent reason. Even when Haider al-Abadi, the prime minister of Iraq, personally orders this money to be sent, it still does not arrive.

The fact is that either side — Baghdad or the KRG — could today buy Kirkuk’s gratitude and loyalty if they were willing to stand up and commit as little as $100m in interim funding. In a telling signpost that both Baghdad and the KRG are politically and economically broken, one of Iraq’s most strategic provinces is up for grabs and neither side can mobilise the leaders or the resources to reach out and help Kirkuk.

Source: The Washington Institute, September 24, 2015

(*) Michael Knights is a Lafer Fellow w

Comment here