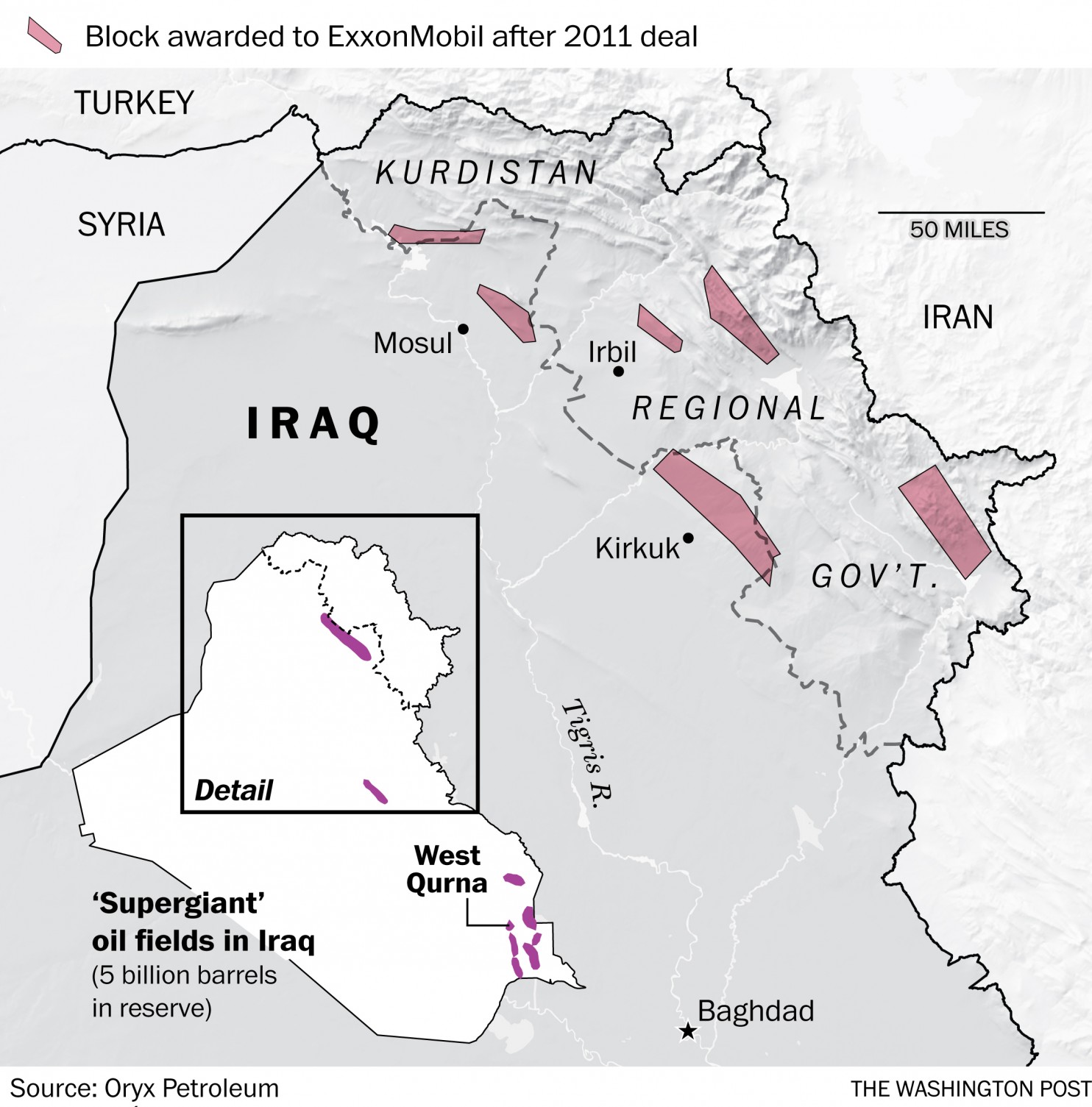

When Ashti Hawrami, the oil minister from Iraq’s largely autonomous Kurdistan region, unfurled a map of untapped oil fields for a team of ExxonMobil officials in the spring of 2011, they saw possibility and profit.

The minister pointed to the blocks that had already been taken by other foreign firms as Iraqi Kurdistan, long at odds with the country’s central government over oil and territory, raced to establish itself as a player on world oil markets. He also showed them the fields that were still up for grabs. Tell me what you want, and we can start negotiating, Hawrami said, according to one former Exxon official who attended the meeting.

It was the start of months of hurried talks blessed by ExxonMobil’s chief executive, Rex Tillerson, and other senior executives back in Dallas. The company was making a high-stakes gamble that new agreements would pay off handsomely if the northern region held billions of barrels of accessible oil.

But the deal overseen by Tillerson, whose confirmation hearings to become secretary of state begin Wednesday, defied U.S. foreign policy aims, placing the company’s financial interests above the American goal of creating a stable, cohesive Iraq. U.S. diplomats had asked Exxon and other firms to wait, fearing that such deals would undermine their credibility with Iraqi authorities and worsen ethnic tensions that had led Iraq to the brink of civil war. A law governing nationwide oil investments was tied up in parliament, and Iraqi officials were rejecting the Kurdistan regional government’s authority to export oil or cut its own deals.

When word of Exxon’s partnership with the Kurds reached Washington, the State Department chided the oil firm: “When Exxon has sought our advice about this, we asked them to wait for national legislation. We told them we thought that was the best

course of action,” then-spokeswoman Victoria Nuland said.

Exxon’s 2011 exploration deal with the Kurdistan region provides a window into how Tillerson, President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the State Department, has approached doing business in one of the world’s most risky, complicated places, where giant energy deals can have far-reaching political effects.

The episode of petro-diplomacy illustrates Exxon’s willingness to blaze its own course in pursuit of corporate interests, even when it threatens to collide with U.S. foreign policy.

When Iraq’s central government threatened to throw Exxon out of much larger, established operations in the south, Tillerson personally intervened, using his executive clout to smooth things over with authorities in Baghdad while making clear his company would weather the political fallout in pursuit of its central goal: a profitable deal.

“It’s a big company that looks for ways to make money like all big companies,” Philip H. Gordon, a former White House coordinator for Middle East policy, said of Exxon. He said the controversial Iraqi Kurdistan contracts reflected a natural corporate instinct to act in the interest of shareholders, not the U.S. government.

If Tillerson is confirmed, “I would hope that he’d realize that he’s serving the interests of the country and not the interests of Exxon,” said Gordon, now a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Lawmakers will weigh Tillerson’s decades-long track record at Exxon this week when they convene to consider his nomination to be the next U.S. foreign policy chief.

The world’s largest oil firm, Exxon has long exercised formidable clout in countries where it does business. The company has not shied away from controversy, inking deals with autocratic governments and speaking out against sanctions, such as those the United States has imposed on Russia, that hurt its bottom line.

Exxon was one of the firms hungry to do business in Iraq, closed to outside investors for decades, after the ouster of Saddam Hussein in 2003. By 2009, the Iraqi government had put its top fields on offer. While the terms of those deals were seen as stingy — paying $1.50 to $2 a barrel — firms signed on anyway, betting that a foot in the door would lead to other, more-lucrative opportunities. Exxon and its partner Shell snared the rights to West Qurna, a massive field in the country’s south.

But Iraq, looking to retain tight control of precious resources after years of U.S. occupation, never offered the more advantageous deals.

“Some said, ‘Let’s take this as an appetizer, not the main course,’ ” said Fadel Gheit, an oil analyst for Oppenheimer & Co. “Then they were told, ‘No, this is the course.’ ”

At their sprawling, bunker-like embassy in Baghdad, American diplomats heralded the new deals as a validation of U.S. ambitions to transform Iraq into a stable, business-friendly outpost in the Middle East. If it was an American company landing one of the country’s biggest fields, all the better.

But Exxon officials were growing increasingly dismayed by early 2011 as they saw their narrow profit margin in southern Iraq all but disappear. To make matters worse, the Iraqi government was constantly in arrears. By the end of that year, it owed Exxon about $1 billion, according to a former Exxon official.

Ali Khedery, who advised U.S. officials in Iraq before joining Exxon in 2011, argued that the Kurdistan region was one way to offset the disappointment in southern Iraq.

Oil reserves in the northern region had not been explored, but its basins appeared to make it “one of the world’s most promising regions for the future [of] hydrocarbon discovery,” one paper said, with potentially as much as 55 billion untapped barrels.

In its capital city of Irbil, the region’s government portrayed itself as a Western-friendly alternative to Baghdad, where car bombs and militiamen continued to keep outside investors away. For Kurdish leaders, establishing the region in world oil markets was a crucial step toward the dream of eventual independence.

Beginning in 2002, Kurdish leaders had welcomed small firms that were willing to brave an untested environment. By 2011, as Kurdish ties with neighbor Turkey improved, a hoped-for export pipeline looked more likely.

But much about doing business in Iraqi Kurdistan remained laden with risk. Since 2003, Kurds had sparred with the Arab-led government in Baghdad over disputed areas and budget revenue. In the years leading up to Exxon’s deal, Kurdish peshmerga troops had come close to open conflict with the Iraqi army, forcing the United States to intervene.

“This was part of a bigger game of political leverage that was going on since the overthrow of Saddam in 2003, taking advantage of a weak central government, an ambiguous constitution,” Denise Natali, an expert on northern Iraq at National Defense University in Washington, said of Kurdish attempts to expand influence through oil deals.

But Khedery said the region remained attractive. “Despite it being far from perfect — the endemic corruption, the factionalism — the bottom-line assessment was that Kurdistan was going to be a much better operating environment than the Arab portion of the country,” he said.

In April 2011, after internal briefings about Iraq to senior Exxon officials, a team from Exxon and Shell met with Kurdish officials. Kurdish and company executives eventually settled on six fields that would be explored by the foreign firms. Afraid of losing out to other firms, Exxon raced to finish the talks. After Shell dropped out at the last minute, the company concluded the contract in October 2011.

When news of the deal broke, some U.S. officials felt they were not given adequate notice by Exxon. Former company officials dispute that account. Either way, diplomats were worried the deal would disrupt parliamentary negotiations over the oil law and undercut their clout with Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki at a particularly sensitive time. For months, U.S. and Iraqi officials had been holding tense talks over a proposal to leave thousands of American troops beyond a departure deadline at the end of 2011. Only a few days after Exxon signed its deal, President Obama abruptly announced the talks had failed: All U.S. troops would be gone by year’s end, officially bringing the war to an end.

In assessing the fallout from the Kurdistan deal, U.S. diplomats were worried Iraq would throw Exxon out of the south, where they had also signed on to a deal that would be important in helping Iraq increase production across its biggest fields.

U.S. officials had long cautioned American firms against signing deals with Iraqi Kurdistan before the oil legislation was completed, but they stopped short of telling them they could not do them — they had no power, former officials said, to do so.

“The U.S. government position with American and other firms seeking to engage in the north was to explain the complexities, warn of the unsettled nature of the laws applying to that, point out the complications in trying to get any oil discovered and produced out of Kurdistan, given the position of the Iraqi government,” said then-Ambassador James Jeffrey, who now acts as an adviser to Exxon.

Adding to the friction, three of Exxon’s new blocks were in areas claimed by both Baghdad and Irbil, outside of the regional borders set before 2003. Despite the unresolved status of those areas, Kurdish officials argued that they, not the Iraqi government, controlled those plots. Exxon lawyers concluded contracts for those areas would be legal.

When Hussein al-Shahristani, who was Iraq’s oil minister at the time Exxon signed its deal for West Qurna, learned about the deal, he was irate.

“The position of the Iraqi government was always to reject this, and the company was informed that this was a violation of Iraqi law,” Shahristani said. While Iraq sought to deal with foreign firms “with trust and good intentions,” he said, “this move by ExxonMobil shook our confidence in them.”

[Tillerson reveals personal wealth of up to $400 million]

In securing the Exxon deal, Iraqi Kurdistan had wooed one of the largest U.S. companies and got it to lay claim to disputed areas, creating a foundation for greater independence and clearing a path for other companies, including Chevron, to follow.

“People said, ‘This is a boomtown.’ You couldn’t talk rhyme or reason, they were so excited about it,” Natali said of companies’ view of their Kurdistan oil prospects. “They created a bubble that ignored history, domestic politics, geopolitics.”

Bayan Sami Abdul Rahman, Irbil’s envoy to the United States, said that Kurdistan’s oil contracts “have put the Kurdistan region on the global energy map and have helped to internationalize our economy after years of enforced isolation.”

Officials in Baghdad saw Exxon’s decision to sign up for blocks such as Bashiqa, which lies entirely outside the current Kurdistan regional borders, as siding with Kurds in the land dispute.

“When any company comes and works in those areas, it’s clear that it’s contributing in inflaming a conflict and pouring oil on the flames,” Shahristani said.

Alan Jeffers, a spokesman for Exxon, said the company followed “all laws and regulations” in pursuing the Iraqi Kurdistan deal. “Issues involving management of hydrocarbon resources in the Kurdistan region of Iraq are for the Iraqi people to resolve,” he said.

Shahristani, who by the fall of 2011 had become deputy prime minister for energy matters, advised Maliki to withdraw the Qurna contract and take Exxon to international arbitration.

As Baghdad made threats, Exxon tried to convince Iraqi officials that greater production would benefit the country in the long run. In January 2013, Tillerson flew to Baghdad and met with Maliki himself.

There, Tillerson told Maliki that Exxon was “prepared to stay and operate in both [parts of the country] and it was the Iraqi government’s choice,” said a former senior State Department official who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue. “He didn’t blink. In the end, he came away with that deal.”

By that point, the stakes in assessing a potential expulsion were already lower for Exxon, which had begun selling off parts of its unprofitable West Qurna interests. The Iraqi Oil Ministry, despite its threats, never brought legal action against Exxon, but it did seek to exclude Exxon from a later auction and push it out of the southern production-boosting project.

“I think a big part of it was Tillerson,” the former official continued. “He personally went out and negotiated with all the individuals including Maliki and explained why it was in their interest to have the largest private oil company in the world operating in Iraq and the negative signals that would be sent if they would leave them out.”

Even after weathering the blowback from Baghdad, disappointing exploration results prompted Exxon to pull out of three of its six northern blocks in early 2016, walking away after spending over $500 million, according to the Iraq Oil Report. Like other firms, Exxon had found that Iraqi Kurdistan was not as good a deal as hoped.

One official with a rival oil company, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a another major energy firm, said companies such as Exxon approach doing business in risky, politically unsettled places such as Iraq with a decades-long perspective. “You may not like the administration in any particular country today, but in 10 years time there’s going to be a different government,” he said.

In the end, he said, big firms “have to go to where the oil is and then manage the politics around that.”

Mustafa Salim in Baghdad, Loveday Morris in London and Karen DeYoung and Julie Tate in Washington contributed to this report.

Source: The Washington Post, January 7, 2017

Download PDF: How Exxon, under Rex Tillerson, won Iraqi oil fields and nearly lost Iraq. By Missy Ryan and Steven Mufson

Comment here