Despite all the diplomatic posturing and domestic politicking, the day after the referendum may look very much like the day before.

On 25 September, the residents of Kurdish-controlled areas inside Iraq will have the opportunity to vote in a referendum on their preference for the future of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), a semi-autonomous region within Iraq’s current borders. The referendum ballot asks: “Do you want the Kurdistan region and the Kurdistani areas outside the region’s administration to become an independent state?”

Being that the majority of voters in the balloted areas are ethnic Kurds with a strong history of seeking self-determination, the result will almost certainly be a Yes. However, no matter what the residents of Kurdish-controlled areas decide, the referendum has no immediate administrative effects. There is no mechanism for a part of Iraq to secede from the country, so the referendum will not trigger a “Kexit” the same way that the recent UK referendum on whether to stay in or leave the European Union triggered “Brexit.” One may well ask, why then are they holding a vote and why now?

REFERENDUM RATIONALE

Domestic politics in Kurdistan has certainly shaped the timing of the referendum. The KRI’s president Massoud Barzani has exceeded his term in office and wants to symbolically begin the process of independence before he steps down during the next KRI elections, scheduled for 1 November.

Another reason for the referendum is to create a fresh mandate for the Kurds to get international backing for an eventual negotiated exit from Iraq and the declaration of a new UN-recognised state, probably within the next five to 10 years. The KRI was autonomous since Saddam Hussein’s forces withdrew from parts of northern Iraq at the end of the 1991 Gulf War, with the Kurds developing their own parliament, ministries and armed forces. They even used a different currency from Saddam’s Iraq and received 17% of Saddam’s oil revenues under a UN-administered deal.

Looking back, most Kurds wished they had stayed in this arrangement. Instead, they agreed to provisionally rejoin Iraq in the wake of the 2003 US-led invasion, in return for US and Iraqi promises that the KRI would continue to operate semi-autonomously, receive earmarked funding from the federal oil revenues, and begin the process of negotiating permanent border changes and perhaps independence with the federal government in Baghdad.

However, Baghdad began to fight over the KRI’s semi-autonomous status and negotiations became deadlocked. Barzani recently described the decision to stay inside Iraq as “a big mistake.”

NOT QUITE SOVEREIGN

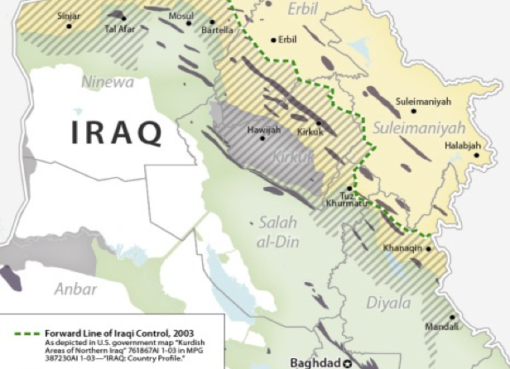

In the last 14 years the Kurds have expanded the areas that they physically control, to encompass many areas that contain oil reserves or where large numbers of non-Kurds live, such as Kirkuk province (to view maps illustrating the territorial situation, visit the BBC webpage for this article). The Kurds have also built up 600,000 barrels per day of oil exports by attracting international investors and exporting the oil through the Iraq-Turkey pipeline to Mediterranean loading terminals. This is an incredible achievement for a land-locked stateless people surrounded by suspicious nations.

But the KRI still lacks many of the final characteristics of a state. The region cannot secure sovereign loans at acceptable interest rates or receive end-user certificates to purchase arms in the same manner as UN-recognised states. Kurdish oil sales are periodically threatened by Baghdad with legal challenges. Baghdad controls Kurdish airspace. KRI residents must use Iraqi passports and suffer from the same visa restrictions as Iraqis, even though the Kurdistan region is much safer than federal Iraq.

WHAT NEXT?

The KRI leadership is likely to press ahead with the referendum because Iraq, Turkey, Iran and the international community failed to craft an effective combination of threats and promises to compel a postponement. Turkey will rhetorically condemn the referendum but will probably not close the border or Kurdistan’s vital oil export pipelines. Iran, federal Iraq forces and Iranian-backed Shia militias are unlikely to seriously threaten the well-prepared Kurdish defences. Much of the bluster from Iran and Turkey seems designed to suppress a potential domino effect that could encourage Iranian, Turkish (and Syrian) Kurds to greater separatist efforts.

Many senior Iraqi politicians have confided to me in private that they believe the KRI is slowly and irreversibly becoming an independent state. But no Iraqi leader can say this publicly, not least when local and national elections loom in Iraq in April or May 2018. No Iraqi prime minister wants Iraq to formally be broken up on his watch.

This dynamic will drive Baghdad to kick the can down the road by offering new negotiations on the devolution of greater powers to the KRI. Both sides will debate the thorny issue of Kirkuk and other so-called disputed areas — mostly controlled by the Kurdish-majority KRI but inhabited by Kurds and non-Kurds and still claimed by Baghdad. These kinds of talks have been happening ever since 2003.

What this all means is that the day after the referendum may look very much like the day before. On 31 December 1999, the world expected the Y2K bug to switch off all computers, but on 1 January 2000 nothing much had changed. The Kurdistan independence referendum may be similarly thrilling until the event but anti-climactic afterwards.

Michael Knights, a Lafer Fellow with The Washington Institute, has worked in all of Iraq’s provinces and spent time embedded with the country’s security forces.

Source: The Washington Institute, September 18, 2017

Comment here