The exhibition takes a holistic approach to the celebrated monument, from its construction to its stunning re-creation.

New York

We all used to visit museum shows about antiquity to feast our eyes on gorgeous objects and imagine the cultural wealth of, say, ancient Egypt, Greece or Rome. These days, curators are increasingly changing and deepening the experience. Their institutional ethos has evolved to include hitherto overlooked layers of narrative around the artifacts—how they were excavated; how they were recorded and preserved; the assumptions made about them by archaeologists, right or wrong, at the time and why. There’s a new emphasis, also, on the life of locals who crafted the objects centuries ago or helped with the digs. We get to share the realities of historically distant others more fully, rather than gaze passively on the loot they produced or uncovered. We understand better how our thinking differs from that of the past, and how we, too, might have thought back then.

This new ethos perfectly suits the folks at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, because ISAW is primarily a research establishment linked to New York University, but one that also serves as a museum sans a permanent collection. Their latest show, “A Wonder To Behold: Craftsmanship and the Creation of Babylon’s Ishtar Gate,” uses 118 illustrative objects from top museums around the world to profile the celebrated monument from multiple angles, from its construction and ritualistic purpose to its ultimate excavation and near-miraculous re-creation.

Named after the city’s presiding goddess, Ishtar, the gate and its Processional Way were built during the rule of King Nebuchadnezzar ll (reigned 604-562 B.C.) to act as the ceremonial nerve-center of a great empire stretching from Iran to Egypt. By the time German archaeologists arrived at the ancient site in 1899, it was nothing more than high ridges of rubble glittering with glazed fragments. No historical record existed of what lay there. The digs lasted until 1917, led by Robert Koldewey, famed in history as the man who uncovered Babylon.

So it’s perfectly proper that the show’s first display is of a wooden box housing crumbled mud brick. Nearly 800 such boxes were shipped back to Germany, where the bricks were painstakingly reassembled and made whole with modern elements until a reasonable (though smaller) facsimile of the magnificent structure was raised in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum, where it still sits. But first, experts had to envision what the original looked like, its shapes and colors and proportions. We see a 1901 watercolor by chief restorer Walter Andrae that depicts the clues he followed: a system of fitter’s marks inscribed on each brick showing where and how it clicked into place. We see a case of such complete bricks. We see a large mud-brick panel still crisscrossed by the matting it was dried on over 2,500 years ago. And bricks with the name and titles of Nebuchadnezzar. Nearby stands a statue of an earlier Mesopotamian king, Ashurbanipal, with a brick on his head. Such was the value placed on the humble earthen material throughout the ancient Middle East. The gods made living beings out of clay, the stuff of creation.

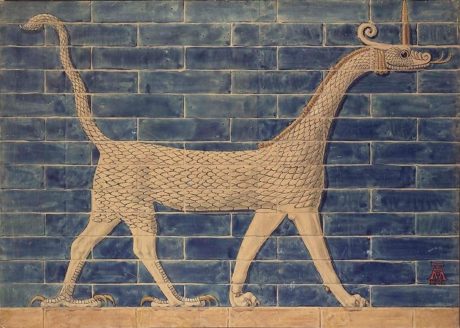

Reconstruction of bricks with a mushussu-dragon from the Ishtar Gate (1902) PHOTO: STAATLICHE MUSEEN ZU BERLIN, VORDERASIATISCHES MUSEUM

The show gradually acquaints us with the divine nature of the construction for Babylonians—the process, the materials, the participants and the finished product all were sacred. Laborers carried priestly status. Their acts of crafting paralleled the gods’. Molds and kilns evoked the wombs and fertility of goddesses. We see just such a clay mold for a female figurine from the second millennium B.C.

As the years passed, artisans upped their game and made exquisite blue and turquoise bas-reliefs of creatures betokening deities. We see a panel depicting a striding lion, one of 120 that graced the original monument, almost life-size, against a cerulean background. Nearby, a slender dragon ambles along. These were fierce supernatural beasts, protectors of the city, set into the Processional Way walls. Approaching Ishtar Gate, you walked toward and past them and into the inner city, condignly awed. Andrae reconstructed them from myriad pieces. We see also his exquisite watercolor depicting a floral panel he partially recomposed from Nebuchadnezzar’s own throne-room entrance. His ethereal artist’s impression of Babylon’s sublime aesthetics exalts us doubly.

What we absorb, what the curators reveal to us, is the sensation of sacred refinement at the dawn of civilization. In those days, divinities were not personified—“aniconic” is the term. They didn’t abide in some distant empyrean but were felt to be everywhere. We realize that no dividing chasm existed between lowly clay and supernal deities, between the sublime and the fierce or between the tactile and the evanescent. We have surely traveled a long way from that state of mind. Then we see a modest brown clay fragment inscribed with the mighty king’s signature almost touching the little paw-print of a dog that likely wandered onto the sacred drying clay. We realize that Babylon is not so far from us after all.

Source: The Wall Street Journal. January 4, 2020

Comment here