Iraq depends on oil revenues, which have plummeted. The country is so desperate it is asking for donations to help it weather the pandemic.

BAGHDAD — When Iraq recorded its first cases of coronavirus, its health minister asked the government for $5 million in emergency funds. But there were no funds to be had.

“There is no money and we are in a difficult situation,” said the minister, Jaafer Sadiq Allawi, as he appealed for help from a cleric at a wealthy Shiite shrine.

Iraq is cratering on almost every front. Oil revenues, the government’s main source of income, have plummeted as the world price of oil has crashed and the government has resorted to asking for donations to help it weather the pandemic.

A nationwide curfew, imposed to slow the spread of the virus, has shut down commerce and thrown the vast majority of nongovernment workers out of jobs.

The government itself is foundering after antigovernment protests ousted the prime minister in November and Parliament has been unable to agree on new leadership.

On top of that, Iranian backed militias still launch regular attacks on American troops — the latest on Thursday when two rockets landed near the American Embassy in the Green Zone — threatening to drag Iraq deeper into the cross-hairs of Iranian-American hostilities.

“These are the worst days we have lived through in Iraq,” said Riyadh al-Shihan, 56, a military veteran. “I lived through the Iraq-Iran war, the uprising, Saddam Hussein, but these days are worse.”

A strange silence has descended over much of Baghdad, a capital of eight million people. The highways out of the city are mostly free of cars because of travel restrictions and on Friday, when most people are off work, the usually crowded parks were empty thanks to the curfew.

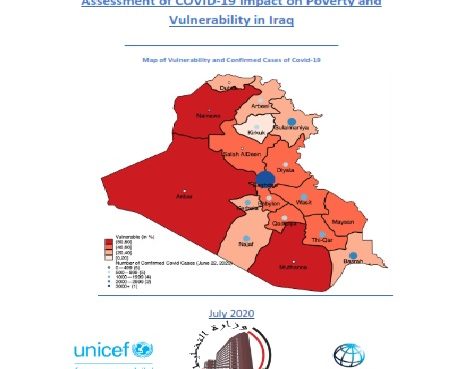

Iraq had 547 confirmed cases of the coronavirus by Sunday, but has been doing extremely limited testing. The true number is thought to be many times greater.

What makes the situation especially bleak is that the combination of crises has effectively wiped out almost the entire economy, said Basim Entiwan, an economist in Baghdad.

“The current economic situation is worse than what we have seen before because all productive sectors have been suspended,” he said. “There is no industry, no tourism, no transportation, and to some extent agriculture is affected as well.

“We are seeing a nearly complete paralysis of economic life and that comes on top of the ongoing protests. And also borders are blocked both within the country between provinces and on Iraq’s frontier with other countries.”

Oil is now selling for half the price, or less, than it did three months ago because of a price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia. It has dropped from about $60 a barrel at the end of December to less than $30.

The price plunge has dealt a severe blow to oil-dependent economies, said Fatih Birol, the executive director of the International Energy Agency, based in Paris. But Iraq, he said, stands to take the hardest hit.

“Iraq is the number one country in terms of impact because it does not have financial reserves and because 90 percent of its revenues come from oil,” he said. “And all these economic pressures are coming in an already very tense political environment.”

Iraq’s reserves are on the order of $62 billion, Mr. Entiwan said, which the International Monetary Fund considers inadequate.

The government has created a fund for donations to help it through this period, which has collected less than $50 million in pledges, said Sayid Jaiyashi, a member of the National Security Council who is also on the prime minister’s coronavirus crisis committee.

Even if the pledges come through, they will hardly make a dent. The government is currently running a monthly deficit of more than $2 billion just for current expenditures.

Iraq has a limited private sector, some of it supported by government contracts, as well as a thriving informal economy. But both have been dealt a body blow by the coronavirus because of the nationwide 24-hour curfew, which has been extended until April 11.

Construction workers, street vendors, domestic workers and taxi drivers have been forced to stay at home. Because most of them live day to day on what they earn and have little or no savings, they could soon be on the edge of hunger.

In some neighborhoods, the police are enforcing $80 fines for anyone who tries to sell goods on the sidewalk — far more than most of them could make in a day.

How long such tremendous economic pain can be borne is hard to say, but it is especially difficult in the absence of political leadership, Iraqis said.

Iraq was already facing its worst political crisis in years before the virus hit and oil prices dropped. Hundreds of thousands of protesters have taken to the streets since October, demanding a new government, an end to corruption and a curb on Iranian influence.

While the numbers had dwindled with the colder and wetter winter weather, curfew has not been rigorously enforced at the protest sites and a few hundred protesters remain in the major squares in Baghdad and other cities. As they continue to keep pressure on the government, they also now pose a potential health risk for spreading the virus.

“This crisis is more difficult because, to be honest, we do not have a government,” said Hassan Ali, 20, who was making a pilgrimage to a Shiite shrine in Baghdad despite being urged to stay home, a warning he discounted because he has no faith in the government’s advice.

“The government is very weak, it’s very tired, they have no solution for the crises, no solution for the youth who have no jobs. With corona it is very difficult because no one can rely on the government.”

In many ways he is right. In mid-March, the health minister, Mr. Allawi, said he would need $150 million a month to purchase the equipment he needs to fight the virus. The donor fund has only collected a fraction of what the ministry believes will be required to protect health care workers, house and treat patients.

So far not a single politician has spoken directly to the country about the financial obstacles ahead. In recent addresses encouraging citizens to follow the instructions of the Health Ministry both the caretaker prime minister, Adel Abdul Mahdi, and the president, Barham Salih, mentioned the economy in passing but did not explain the situation.

One reason, said economists, is that they have little comfort to offer. Iraq has no control over worldwide oil prices and while consultants, foreign governments and economists have all pushed Iraqi leaders to diversify the country’s economy, it has not happened. Some of the reasons are practical, including the country’s armed conflicts, but some are cultural.

For more than 60 years, Iraq’s economy has been dominated by the government: Its oil companies are majority government owned and so are its factories and many of its companies. Even some of the private ones count on government contracts, making them often disproportionately dependent on the public sector.

For many people, the only worthwhile job is one with a government paycheck. So some 4.5 million Iraqis, about 30 percent of the work force, are either salaried government employees or have government contracts, said Mr. Entiwan, who was an economic adviser to former Prime Minister Haider Abadi.

So far the government has not cut salaries, which account for more than 40 percent of the government budget, but it has been forced to consider pay cuts for mid- and high-level employees, said Mudher Muhammed Saleh, an adviser to Mr. Abdul Mahdi. Another possibility under consideration was to require Iraqis to pay for their electricity, which few now do, he said.

When the price of oil crashed in 2014, Iraq was aided by access to $4.5 billion in financing from the International Monetary Fund. However, in the midst of the coronavirus many countries are hoping for largess from the IMF.

“In 2014, Iraq was fighting against ISIS and could bank on the support of its partners, on other countries, but now the whole world is occupied with the coronavirus and it may be more difficult to raise the money,” said Mr. Birol, of the International Energy Agency.

“The most important issue right now is the health system,” he said. “If the health system cannot get finances from the central government, it will have serious implications for coronavirus and for social stability.”

Falih Hassan contributed reporting.

Alissa Johannsen Rubin is the Baghdad Bureau chief for The New York Times.

Source: New York Times, • March 29, 2020

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/29/world/middleeast/virus-iraq-oil.html

Comment here