Prepared by Professor Ali A. Allawi

Presentation to the US-Europe-Iraq Track II Dialogue Convened by the Atlantic Council and Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung and supported by DT Institute March 2-4, 2020 in Berlin

I Introduction

The Theoretical Framework

The nexus of administrative structures, organisations, laws, customs, and ideas are at the heart of economic transactions. They directly affect transaction costs and impinge on the efficiency of markets.

The formal rules of a society (laws and regulations), informal constraints (conventions and codes of conduct), and the enforcement mechanisms of both are the boundaries inside which human beings interact.

Administrative structures and formal rules are then expressed through organisations that include political bodies, economic units, social and religious bodies, and educational institutions.

In my view, based on personal experience in multilateral institutions, private business and government, these structures are one of the key determinants of economic growth and development.

They are possibly the most important for economies and societies emerging from prolonged conflict and strife.

The planning and management of institutional change has undergirded the economic development of societies as divergent as post-war Germany and Japan, Korea and Taiwan, and now, of course, China.

Changing formal rules is the easy part. Constitutions can be changed overnight and laws and regulations overhauled.

But the norms that provide legitimacy to these rules take far longer to modify. Transposing the formal rules of successful societies to another society is not always a happy or successful experience.

Positive institutional change that enhances economic performance is directly linked to the political structures that define and enforce the economic rules of the game.

Stability of political institutions, the soundness of policies, the quality of law-making, and the just enforceability of contracts and agreements are essential for enhanced economic performance.

II Defining Corruption

Probity of public officials and a sense of the primacy of the public interest over private gain in the political class are vital for successful institutional change. This is where corruption comes in.

According to Transparency International, “Political corruption is a manipulation of policies, institutions and rules of procedure in the allocation of resources and financing by political decision makers, who abuse their position to sustain their power, status and wealth.”

Defining Corruption

“Corruption benefits the few at the expense of the many; it delays and distorts economic development, pre-empts basic rights and due process, and diverts resources from basic services, international aid, and whole economies. Particularly where state institutions are weak it is often linked to violence. In part because of corruption, for millions ‘democracy’ means increased. insecurity and ‘free markets’ are where the rich seem to get richer at the expense of everyone else.”*

- *From Michael Johnston, Syndromes of Corruption

Corruption reduces economic growth by misallocating resources. The costs overwhelm any purported gains from greasing the wheels of bureaucracy.

Several studies have exhibited the negative impact that corruption has on growth and investment.

- There are two kinds of corruption: Capture– where a bribe has the effect of diverting public officials from their duties (i.e. winning procurement contracts) and Extortion– where the public official needs to be bribed to perform his/her duties (i.e. paying to have garbage collected).

- Capture is usually much harder to establish than extortion.

In advanced countries, extortion is rare but capture can occur.

In developing countries corruption is widespread and takes the form of both capture and extortion

Measuring corruption is problematic, but Transparency International has created an index based on the perceived level of corruption

- On the TI Index , Iraq has consistently been in the lowest band of countries with the most corruption. Out of a possible perfect score of 10 (no corruption), Iraq has rated between 1.5 to 1.8 between 2007 and 2019.

- In 2007, Iraq received the worst score in the world on the TI Index, rising marginally to 168th out of 180 countries in 2019

Johnston identifies four different ‘syndromes’ of corruption developing his corruption model:

- Influence Markets, where corruption revolves around the use of wealth to seek influence within political and administrative institutions – often with politicians putting their own access out for rent. Basically, the stakes are the details of policy.

- Elite Cartels,where interlocking groups of top politicians, business figures, bureaucrats, military and ethnic leaders share corrupt benefits among themselves. They can build networks and alliances that solidify their power and stave off the opposition. Corruption of this sort may well be highly lucrative, but it is also a strategy for forestalling political change

- Oligarchs and Clans,where a relatively small number of individuals use wealth, political power, and often violence to contend over major stakes, and to reward their followers, in a setting where institutional checks and legal guarantees may mean little.

- Official Moguls,where state elites operate in a setting of very weak institutions, little political competition, and expanding economic opportunities. Here the stage is set for corruption with impunity. Official Moguls – powerful political figures and their favourites – hold all the cards.

- Iraq exhibits all the varieties of the corruption syndrome, but veers more towards the prevalence of oligarchs and clans, and the predominance of official moguls.

- In Iraq, there is no dividing line between politicians and businessmen. The vast majority of politicians think their office entitles them to get rich at the public expense.

- The presence of oligarchs admits to the possibility of some formal ordering of the economic sphere, in the sense there is a presupposition of the existence of large corporations and organised commercial interests. This is generally absent in Iraq, except perhaps in the telecoms sector and the power generation sector.

‘‘Official Moguls’’ has a double meaning: officials and politicians enrich themselves through corruption more or less at will, at times moving into the economy by converting whole state agencies into profit- seeking enterprises, and ambitious businesspeople with official protection and partners take on a quasi- official status as they build their empires.

Either way the locus of power lies not within the state but with officials who use political leverage to extract wealth.

In Iraq, the official moguls syndrome has now expanded to include semi- state actors, who have been given specific economic sectors to exploit for their private gain. These include the partly integrated militia forces, who have clear control over a number of smuggling and extortion rackets linked to the oil industry and defence services.

III Governance

In 1992 the World Bank published the report, “Governance and Development,” in which it defined governance as the manner in which power is exercised in the management of a country’s economic and social resources for development.

It was the first time that World Bank strayed from its explicit mandate of limiting its operations and loan conditions to the non political sphere.

Ever since, “governance” has become a euphemism for mismanagement and abuse of power, and attempts to define and

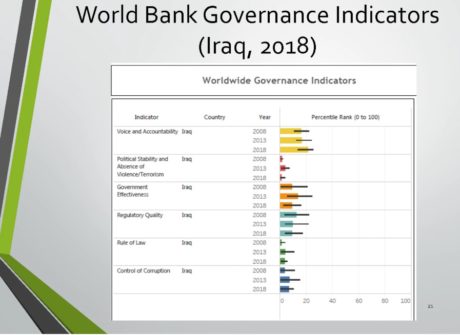

In 1996, the World Bank produced its Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), which have become the standard by which governance issues in developing countries are measured. The WGI consist of six composite indicators of broad dimensions of governance covering over 200 countries since 1996: Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism, Government Effectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption.

Iraq’s Governance Ratings on WGI

- Voice and accountability: The extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. This is Iraq’s best performing governance indicator, perhaps reflecting the formal freedoms and rights that are constitutionally guaranteed, and the electoral process. Nevertheless, Iraq ranked in the lowest 22 percentile category, worldwide, in 2018.

- Political stability and absence of violence: The perceptions of the likelihood that the government will be destabilized or overthrown by unconstitutional or violent means, including domestic violence and terrorism. Here Iraq’s performance is amongst the lowest in the world, ranking in the lowest 1.4 percentile category in 2018.

- Government effectiveness:The quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies. Iraq ranked in the lowest 9 percentile category in 2018.

- Regulatory Quality:The ability of the government to provide sound policies and regulations that enable and promote private sector development. Iraq also scored abysmally here, in the lowest 9 percentile category in 2018.

- Rule of Law: Abide by the rules of society, including the quality of contract enforcement and property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. Iraq’s performance is even worse in this instance, at the lowest 3 percentile category in 2018.

- Control of Corruption:The extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interest. Iraq scored at the level of the lowest 7 percentile category in 2018.

IV. How did we get here?

A brief look at Iraq’s history

From the Founding of the State (1921) to 2003

❖ Since its founding in 1921 and until the 1980s, Iraq was not perceived as a corrupt country.❖ Several reasons have been advanced for this:

- Robust norms and conventions, based on religious and ethical values governed economic transactions. These had been honed over centuries

- Strong checks and controls over bureaucratic decision-making and administrative procedures. These were mainly established during the mandate period (1921-1932) and persisted into the 1970s

- Enforcement of sanctions on transgressors through a reasonably just legal system

- A relatively well-developed sense of the public interest amongst the political class, in power or in opposition

- Few leaders at the height of power (whether monarchical or republican, post-1958) were in the business of amassing personal fortunes

- Revenues of the state sector were relatively modest (until the early 1970s) and thus opportunities for graft and corruption were limited

❖ By the 1970s, matters began to fundamentally alter:

- Vast expansion of the state sector, through nationalisations but above all by an explosion in oil revenues

- Rising incomes thus obviating the need for extortion-type corruption

- Imposition of a rigid ideological framework on the country that stressed nation-building and loyalty to the single party state. Government packed with “believers”

- Draconian measures against transgressors including public executions of corrupt officials and businessmen

These changes masked a collapse in the traditional institutional norms and conventions that governed economic and social transactions as the population was subjected to a modernising campaign that stressed the break with the past.

The “fear factor” and ideological fervour replaced religio-ethical norms and conventions as the main enforcement tool to prevent the occurrence of widespread corruption

The Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) stressed the administrative system but did not materially alter the landscape of corruption in the country.

The main reason was that the state managed to dampen the true resource cost of the war by massive foreign loans (circa $140 billion on which it subsequently defaulted). Standards of living and income, especially in the public sector, were not materially effected.

❖ The beginning of the decay in the formal institutional rules of society could be traced from the 1970s onwards:

- The single party state necessarily privileged its own members in administrative appointments and promotions. Rules and procedures were often bent or ignored

- The judicial system became compromised as it was subject to direct interference from the executive.

- Property rights became tentative with widespread illegal confiscations and sequestrations especially of those considered “enemies of the state”

- Illegally seized property was often transferred at give-away values to privileged members of the ruling groups, thereby compromising the notions of trust and fairness that underpinned economic transactions. A class of people arose who benefitted directly from illegally seized assets

- A new culture arose that sanctioned the illicit acquisition, transfer, and use of private and public assets if it came in the form of a gift, favour, or bequest from political powers

- By the end of the first Gulf War (1991), Iraq was faced with catastrophic economic, social, and administrative collapse.

- International sanctions severely curtailed government revenues and Iraq’s trade, accelerating inflation and collapse in incomes

- With falling incomes, and the general weakening of the state’s repressive apparatus, bribery (extortion) became widespread amongst public officials.

- Teachers received bribes to give passing grades on exams; doctors refused to treat patients unless paid under-the-table; routine dealings with government officials involved graft and so on.

- The sanctions economy also produced a widespread network of smugglers and fixerswho dealt routinely in bribes and corruption. The state relied on them for additional revenues (e.g. from oil smuggling) to circumvent the restrictions of the sanctions regime

- Similarly, the sanctions economy necessitated the establishment of direct state mechanisms for the provision and distribution of essential items for the people’s needs.

- The public distribution system (PDS) was established for the procurement and distribution of foodstuffs and other essential items to the entire population. This programme was relatively graft-free, partly because of its vital role in maintaining public order, and partly because of the continuing “fear factor”

From 2003 to the Present

At the onset of the 2003 invasion, corruption levels in Iraq had risen markedly, and institutional decay was everywhere:

➢ A bloated bureaucracy with civil servants paid a pittance with widespread corruption in the form of extortion

➢ A degraded judiciary whose rulings could always be overturned by the executive

➢ A decaying single party state that abandoned its original ideology

➢ A crisis economy dominated by ad hoc programmes and structures designed to meet the basic needs of survival.

➢ The rise of a partly criminal “biznissmen” class that fed off the sanctions programme and its links to the security apparatus of the state. These groups dominated the trade in illegal oil exports, cigarette smuggling, and in sanctions-related rackets.

➢ The decay of the former institutional rules, behaviour, and constraints that governed economic transactions

- The CPA administration paid no attention to these factors as it sought to, in quick order, make-over the country and then abandoned that effort.

- The chaos, arbitrariness and shallowness of the CPA’s “reforms” created the perfect platform to thrust Iraq into the lowest ranks of corrupt countries.

- These conditions were further exacerbated by the Iraqi governments that took over the mismanagement of the country since 2004

- The removal of the upper tiers of the bureaucracy for their Baathist affiliations – often for very good cause – created a leadership vacuum in the bureaucracy. This was filled by lower grade civil servants who were either incompetent, under-equipped for the task, or who had been sidelined by the previous regime for malfeasance or negligence

- Careless and chaotic packing of the government agencies by cronies and hangers-on of the new political class created a new layer of bureaucrats who had little or no training in modern administrative practices, duties, and constraints

- Job-hungry exiles returned in the tens of thousands with expectations of government posts and sinecures. A psychology of entitlement to government perks was a concomitant to their periods of exile

- Chaos, arbitrariness, incompetence, self-dealing, and plain ignorance characterised economic policy-making, further exacerbating the confused drift of the government and creating ample opportunities for unscrupulous and corrupt people to take advantage of the prevailing disorder.• Rent-seeking by businessmen, government officials, ministers, and foreign adventurers became the assured path to enrichment. The main driver behind decision-making for the economy, at least in the public sector, was the frenzy for economic rents. Needless to say the distortions and costs to the economy grew in leaps and bounds.- The new political class, many of whom had spent years in impecunious exile and in degrading circumstances were determined to have their period of suffering requited by feeding at the public trough- Leaders of this new order were equally determined to amass personal fortunes through their control over key ministries and government agencies- Whatever controls on corrupt practices had existed prior were severely weakened by a frightened and confused bureaucracy, a broken judicial system and the general degradation of the ethics of dealings and transactions- The old sanctions-busting criminal and business networks reasserted themselves often in partnership with the new political class, thereby creating a strong incentive to maintain the “crisis” economy of Iraq.- A “perfect storm” that favoured the stratospheric rise in corruption evolved in the 2004-2019 period. In spite of the astounding levels of plunder, not a single senior official has been indicted, tried and then jailed for corrupt practices. The only one who had come near to it, a former Minister of Electricity, was incarcerated for a few days and then sprung from jail by a US-sanctioned jail break organised by the Black Water Co! The former Minister of Trade was placed under house arrest after being indicted on a minor administrative infringement.

V. Examples of Corrupt Practices

2003 to the Present

The Integrity Commission, the agency charged with monitoring and sanctioning corrupt practices, is itself prone to corruption in the form of extortion and blackmail of targeted culprits.

Nevertheless, the heads of the Commission constantly complain of their inability to go after miscreants because of political protection.

The Integrity Commission has literally thousands of cases of proven corrupt practices which have lingered in its files with no legal action.

- 2004-2009: Corruption in the imports of oil products Loss of about $1-$1.5 billion through overpricing and undersupplying

- 2014-Present: Corruption in the supply and trade of heavy fuel oil Loss of about $ 400 million per annum

- 2006-2010: Corruption in the Ministry of Defence purchases of military equipment from the former Warsaw Pact countriesLoss of about $300 million

- 2009: Corruption in the Ministry of Interior in the supply of bomb- detection equipment: Loss of about $200 million through serious overcharging (useless equipment costing about $60 per piece sold for $16,000 each; Source: New York Times)

- 2008-2014: Corruption in the Ministry of Transport: Purchase of Bombardier aircraft, opaque port terminal licenses, truck transport contracts: Loss of about $500 million

- 2004-2019: Municipality of Baghdad: Major water works and sewerage contracts; land transfers and sales: Loss about $2,500 million

- 2004-Present: Ghost workers in government ministries, mainly the Ministry of Defence and Interior: Loss of about $250 million per annum

- 2004- 2010: Ministry of Sports; Alleged corruption in the building of stadia

- 2004- 2016: The Haj and Umra Bureau; Alleged corruption in the procurement of travel and lodging services to pilgrims

- 2004 Present: Corruption in the supply of fertilisers and seeds by the Ministry of Agriculture

- 2004 Present: Corruption in the medicines procurement agency of the Ministry of Health, Kimadia.: Losses reach about $200 million per annum

- 2010 Present: Corruption in the award of hospital construction projects

- 2006 Present: Sustaining a large gap between official exchange rates for current account transfers and parallel market rates of between 3% 8%. Approximately 10% of currency purchases “round trip” between the official and parallel rates totalling about $750 million per annum in corruptly inspired leakages.

- There is alleged corruption in the procurement of loans, advances and guarantees from all the state-owned financial institutions such as Rafidain Bank, Rashid Bank, and the TBI

- There is alleged corruption in the land dealings of the religious endowments (Awqaf) and the transfer and sale of state land controlled by the Ministry of Finance

- The opaqueness of the production-sharing contracts awarded by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) to foreign oil companies masks a very probable carried interest to the major political figures of the KRG. The figures, if substantiated, will run in the billions.

- In one of the most egregious acts of self-dealing, legally covered by their inclusion in the annual budgets, are the salaries and perks that the political class (parliamentarians, the Office of the Prime Minister, the Office of the President) has awarded itself

- The costs of maintaining an Iraqi PM is one of the highest in the world (about $ 500 million per annum). The budgets of the Office of the Prime Minister reaches $900 million, most of which is excluded from line accounting; for the Presidency, the figure is about $400 million. In total, the 400 odd members of Iraq’s political class have awarded themselves about $2 billion per annum. The reform measures undertaken recently in 2014 and 2015 could have reduced this figure.

Impact of Corruption in Iraq

- There is little doubt about the costs of institutional decay and corruption to the growth and development of the Iraqi economy.

- The qualitative effects of loss of self-esteem, cynicism, mistrust, and a sense of pervasive injustice are equally great if not greater

- Perhaps the greatest loss is the near-terminal decline of the informal rules and codes of conduct, mostly derived from the country’s ethno- religious traditions. These had made it possible to deal and transact in those very long periods in Iraq’s history when there were inadequate safeguards from the judicial system and the political authority

- Nevertheless, the task of reconstructing the institutional framework of Iraqi society, both formal, informal and in terms of their enforcement rules and procedures, must begin in earnest if the oil bonanza does not turn into the oil curse

VI. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Below is a long list of required actions, each one of which is formidable in its own right.

- They are simply indicative of the magnitude of the tasks ahead. They are not exhaustive, but they are, I believe absolutely necessary.

NECESSARY ACTIONS:

- Reform of the Civil Service employment criteria

- Establishment of a National Administrative Institute to train senior civil servants and those expected to rise to leadership position in the administration (such as the Ecole Nationale d’Adminstration school in France)

- Remove key projects and programmes from the purview of ministries

- Establish a statutory independent Reconstruction Board responsible for designing and implementing strategic projects

- Allocate a fixed percentage of oil revenues to the Reconstruction Board

- Devolve the functions of the social ministries (Housing, Municipalities, Labour and Social Affairs, Trade, Health, Policing, Education) entirely to the provinces over a three to five year period

- Raise block transfers to the provinces to meet the added expenditures and responsibilities of the provinces

- Launch an intensive programme of building the capacities of provincial governments

- Overhaul the judiciary and introduce strict competence and probity criteria

- Reform and de-politicise the Inspector General system and the National Integrity Commission

- Create a fiscal police with wide powers of investigation and arrest and special anti-corruption courts

- Establish an authority to retrieve stolen assets or assets corruptly acquired, and to chase, indict and bring to trial corrupt and absconded officials

- Introduce as a matter of urgency e-government throughout the Iraqi government system

- Restructure and recapitalise state-owned banks as a matter of national urgency

- Introduce regional development banks as a PPP to help in the process of investment financing at the provincial level

- Establish a National Economic Policy Board with Iraqi academics and experts supported by a blue ribbon foreign advisory board. The Board will discuss, propose and assess economic policies and strategies.

- Establish a National Oil Policy Board that will set strategic and policy directives for the oil sector

- Establish a National Social Policy Board to set broad social objectives and targets, including income transfers

- Establish a Central Procurement Board that will be responsible for vetting and awarding contracts above a floor level ($20 million?)

- Reform, simplify and streamline taxation policies and tax collection procedures

- Drastically overhaul the company formation rules and devolve the responsibility of licensing from the Ministry of Trade to registered practitioners such as lawyers and accountants.

- Decentralise the letter of credit opening powers from the Trade Bank of Iraq to private Iraqi banks within appropriate rules and guidelines

- Establish an upper house (Senate) in the Iraqi parliament as per the constitutional requirements

Appendix A

Asset Recovery

There are no hard and fast statistics regarding the accumulated proceeds of corrupt practices since 2003 in Iraq.

- Scale of the Problem

The estimates of assets held overseas by Iraqis range from a low figure of $100 billion to a very high figure of $ 300 billion. The best estimates are approximately $125 to $150 billion. The large majority of these assets are illegitimately acquired.This range is corroborated by discussions with officials in the Integrity Commission, together with estimates derived from inferences.My discussions with senior Lebanese bankers and officials of the Banque du Liban indicate that there are approximately $20 billion held in deposits by Iraqis in Lebanese commercial banks, at the onset of the banking crisis in October 2019. These are now effectively frozen inside the Lebanese banking system. (In December of 2019, the scale of Iraqi deposits in Lebanese banks became clear when a single billion dollar deposit by Iraqis in Lebanon’s Bank Med came to light as a result of litigation in a New York court!)It is a fair estimate to infer a similar figure for Iraqi assets held in Jordan, although it is probable that a good percentage of that has been dissipated to accounts and investments elsewhere.

- The other main Middle Eastern destination of Iraqi corrupt funds is Dubai. Here the matter is clouded by the difficulties in obtaining individual non resident banking accounts in the UAE, limiting the disposition of Iraqi corrupt funds to nominee names or through UAE offshore companies. It is very likely that a considerable amount of Iraqi corrupt funds have been invested in Dubai real estate, both residential and commercial. An anecdotal, but oft-repeated figure, of the total amount of such funds is in the vicinity of $25 billion.

- A smaller percentage of Iraqi corrupt funds have been placed with Turkish banksand invested in Turkish property. I have no figures in this regard, but it is very likely that this amount has increased considerably in the past few years, partly by the number of Iraqis now residing in Turkey and holding Turkish nationality.

- Other Middle Eastern destinations for Iraqi corrupt funds include Kuwaitand Egypt but these would be considerably less than the four main countries listed earlier.

- Outside the Middle East, the most significant location would be London. It is highly probable that Iraqi corrupt funds finding a haven in the UK have been transferred from other locations in the Middle East, where they had been effectively sterilised. Money laundering and KYC rules in the UK are very robust for both banks and agents, but until recently, the identity of overseas funds destined for property investments in London have escaped this scrutiny.

- It is very hard to estimate the total amount of funds invested by Iraqis in London property. A great number of Iraqis (probably upwards of 250,000) hold dual British/Iraqi nationality, and many of them are independent businessmen and professionals whose property assets are perfectly legitimate. However, property agents have reported that Iraqi funds have been deployed in large amounts in the wholesale residential property market in London. Entire

- floors of newly built apartments in London’s Nine Elms district and other regenerated areas have been acquired by Iraqis either directly, through nominees or through offshore companies. A good estimate of Iraqi corrupt funds invested in London real estate could be around $10 billion.

- Switzerlandis also a haven for Iraqi corrupt funds but it is somewhat constricted because of the high costs involved in maintaining a Swiss bank account and the lack of sophistication

- and familiarity by the new class of Iraqi ‘businessmen’ with the advantages of Switzerland. I have been informed by a very senior Swiss banker that his bank alone holds about $1 billion of Iraqi funds.

- Another destination for Iraqi funds corruptly acquired is the USA. A large number of Iraqis holding dual nationality worked in various business ventures in Iraq and benefitted from corrupt practices. Generally, US citizens are not subject to the strict money laundering and KYC rules that apply to other nationalities when opening or operating bank accounts in the US. It has proven relatively easy for dual Iraqi/US nationals, who have been indicted in Iraq on corruption, to keep their assets in the US safe from being frozen or sequestered.

- Issues of Asset Recovery

- The process of retrieving stolen assets stashed overseas has proven very difficult. Only a trickle of such funds has been identified, frozen, and recovered by the countries affected.

- Nigeria is the best example of the difficulties in recovering even a single percentage of the totality of these assets. The recovery of assets stolen by dictators have been even more problematic, witness the paltry sums recovered from Mubarak of Egypt, Ben Ali of Tunisia and the Qaddafi clan.

- In Iraq, the problem becomes compounded because of the sheer number and diversity of corrupt actors. These could include ministers and prime ministers, provincial governors, high government officials, leaders of political parties, the ‘economic units’ of political parties, senior military and intelligence officers, militia leaders, parliamentarians, and their accomplices and agents, both Iraqi and foreign. A good number of such people have absconded or emigrated making it even more difficult to trace their whereabouts.

- The assets themselves would have been dissipated or cannot be traced because of a welter of offshore companies, nominees and agents, variety of bank accounts and so on, which effectively disguised the source of the funds.

In addition, an asset recovery imitative would have to contend with the legal and regulatory systems of foreign countries, bank secrecy laws and other measures designed to protect the owners of capital from unmerited interference by state authorities. These would have to be suspended or waived for any asset recovery initiative to succeed.

The costs of mounting such a full scale assault through the labyrinth of national court systems against determined opposition from the lawyers, accountants and agents of corrupt people, will be extremely high and would require a coordinated and fully mobilised team of international lawyers and forensic accountants. (Is it any wonder that Saudi Arabia found it more expedient and efficacious to simply imprison their suspects in a five star hotel and intimidate them into a settlement ?)

Nevertheless, Iraq must begin the process of serious asset recovery for a variety of reasons:

- Public opinion is incensed about corruption and demands that retribution of corrupt individuals takes place.

- The Iraqi state authorities must be seen to be serious about asset recovery, if reform of the country’s political and economic system can ever succeed.

- The moral regeneration and authority of the state structures cannot be established if past corruption is allowed to be forgotten or ignored

- Corruption must be treated for what it is- a criminal activity with huge baneful externalities. Deterrence against its recurrence must be embedded in the administrative structures of government.

III Suggested Course of Action

The GOI should establish an Asset Recovery Authority (ARA), governed by law, that would be charged with the process of asset recovery. The ARA would have full investigative and prosecutorial powers. Crucially, it should also have the power to negotiate settlements where appropriate

The ARA would be empowered to reach out to foreign jurisdictions to seek their assistance in identifying, freezing and sequestering assets derived from corrupt practices in Iraq. The relevant ministries would be geared to assist the ARA in all of these endeavours.

The ARA would establish an Asset Recovery Fund, into which retrieved assets would be deposited, to be utilised in the furtherance of Iraq’s economic and social development.

(*) Professor Ali Abdul Ameer Allawi is the newly appointed Minister of Finance in the Cabinet of Mr. Mustafa Al-Kadhimy

Source: https://www.mushtarek.org/

Download PDF

The Political Economy of Institutional Decay and Official Corruption. – The Case of Iraq

دراسة وبحث ثري جدا بالمعلومات، وهو يمثل توجه وخطة عمل المكلف بالاقتصاد العراقي (الدكتور علاوي) والنهوض به. الدارسة رائعه وادعو الجميع لقرائتها بروية وتمعن. (اتمني ان تترجم للغة العربية بالتعاون مع معد الدراسة وان يتم تداولها بين الطبقة المثقفة العراقية لأهميتها).

كملخص سريع، الدكتور علاوي ركز في معظم بحثه علي الفساد (تقريبا ٨٠٪ من البحث) ماهية الفساد بشكل عام، تاريخ الفساد في الدولة العراقية وتطوره السلوكي والتنفيذي من قبل المؤسسة الحكومية، مع شرح مفصل لانواع الفساد وأشكاله …

الدكتور علاوي يؤكد في هذا البحث، بعدم جدوي اي اجراءات اقتصادية او نقدية او اي إصلاحات دون ان نعالج افة الفساد المستشرية في المؤسسة الحكومية وإعادة تشكيل تلك المؤسسة بنظم واجراءات جديدة وحازمة.

الدكتور علاوي ختم البحث بوضع ٢٣ هدف استراتيجي مهم، واجب التفعيل والقيام به في المرحلة القادمة، مثل مجلس الإعمار وكذلك لجنة وضع السياسات الاقتصادية والنفطية، خصخصة القطاع المصرفي الحكومي والشراكات ..الخ

طبعا، الأهداف الاخري هي أيضا علي درجة عالية من الأهمية مع ما اسلف وكلها مترابط ومتشابك لخلق بيئة عمل صحية ومتوازنة.

اعتقد ان البحث بحاجة الي نقاشات، وترويج وتبني من قبل منصتنا الاقتصادية هذه، فهي تصب في مصلحة العراق والعراقيين.

مع خالص شكري وتقديري للدكتور بارق علي نشره هذه الدراسة.

مبثم حمزة الاسدي