Beginning in mid-July 2015, the major cities of central and southern Iraq, including the capital Baghdad, have been engulfed by one of the largest social protest movements in modern Iraqi history.

The movement erupted spontaneously in the city of Basra, where protests emerged against the deterioration of public services, particularly electricity – at the peak of Basra’s summer heat and humidity. It eventually grew into a broader demonstration against financial and administrative corruption, and against the system of partisan political quota-sharing (muhassasa) in the name of ethnic and communal identities. In sum total, the movement opposed the Islamist elites, symbolizing the failure of political Islam in running state affairs. The recurrent slogan chanted during demonstrations tells it all: ‘in the name of religion the thieves have robbed us.’(Bismil Deen Baguna al-haramiya).

In essence, this social movement shows how the politicization of ethnic and communal identities is losing some of its unifying potency, allowing political, social and class divisions to creep in and segment these grand identities into what may be described a shift from identity politics to issue politics. As stolen funds and the shortage of electricity have no religion or ethnicity, the emergence of issue politics has the potential to transcend communal and ethnic segmentation. As the protests have thus far been concentrated in Shia or predominantly Shia areas, such as Baghdad, the movement signals a strong propensity on part of the wider Shia community to detach identity from the grip of Islamist political elites who lead the state.

Such an attempt to transcend these divisions into intra-communal politics was made in the summer of 2012 during the no-confidence motion to unseat former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki. An intra Shia-Sunni-Kurdish alliance emerged, involving the Ahrar Bloc (the Sadrist Shia bloc), the Kurdish bloc (Masoud Barzani) and Ayad Allawi’s al-Iraqiya bloc, which was predominantly Sunni (only 21 out of 91 MPs were Shia). Therefore, the first exercise of issue politics, driven as it were by political issues, came from above.

The current protests, by contrast, are bottom-up and display unmistakable signs of a popular shift from identity to issue politics. Most probably, this shift will have political, social and cultural consequences that may further the fragmentation of ethnic and sectarian identities from within, and may well alter power relations amongst competing Shia blocs. Eventually, a similar trend, though dormant at the present, will divide Sunni blocs along issue politics. If the protest movement comes to encompass Sunni and Kurdish areas it may create a space within which centrist currents focussing on issues beyond the ethno-communal fault lines may emerge and solidify.

Whatever the outcomes might be, the movement embodies profound social oppositional, dissenting tendencies, hitherto pulsating beneath the surface, stemming from and reacting against the failure of nation-state-building, against the manipulative construction of identities, or the inter-and intra- communal rivalries, the rampant pillaging of the public treasury, and the flagrant administrative and financial corruption.

This paper examines the principal aspects of this social movement and particularly its political, social and economic underpinnings; its social composition, its growth; its message and slogans that are mainly directed against political Islam as a conduit for corruption. In addition this essay will also examine the emergence of young leaderships, and analyse the ramified relationship between the protest movement on the one hand, and the religious centres of authority, the parliament, the Popular Mobilization Units and the Prime Minister’s Office, on the other hand, all in the framework of power struggle and war against ISIS, which overshadows protest politics. The essay is based on field research and an extensive survey conducted between August 2015 and January 2016, the results of the survey constitute the final section.

The findings have already been presented on various occasions at the Carnegie- Beirut Office (Autumn 2015), London School of Economics (July 2016), and The Human Dialogue- London.

The full text of the original report in Arabic will be published as a booklet; the concise English translation is coming shortly.

The field research would have been impossible without the support and cooperation of field researchers who undertook the collection of the material and conduct the field survey (questionnaire) involving around 3000 individuals in 7 Iraqi cities.

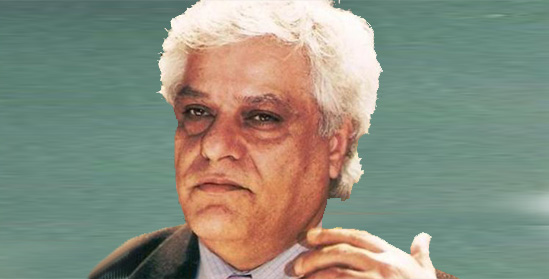

(*) Faleh abdul Jabbar is the Director of the Institute Iraq Studies, Beirut

Comment here