As the kingdom’s model of capitalism without democracy thrives, the prospect of a Saudi century has consequences for us all.

t the centre of the 2018 blockbuster film Black Panther is Wakanda, a hyper-modern civilisation on the African continent kept from the modern world by impenetrable geography and technologically enabled cloaking. Wakanda’s strength and security is provided by a natural resource with fantastic properties, the hardest and lightest metal in the world, vibranium.

Wakandans have invested heavily in basic research, developing their own weapon systems, aircraft and medical technology. The real tension in the film is whether Wakandans should keep their technological wonders to themselves. After a titanic struggle the film ends with the opening of a Wakandan-sponsored outreach centre in a poor part of Oakland, California. Wakanda chooses benevolence.

When movie theatres in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia opened for the first time in 35 years in spring 2018, they screened Black Panther. “It is just great to watch a superhero fighting for his kingdom, surrounded by women empowered as warriors, while the issues of race and colonialism were tackled,” said one woman in attendance. The reference to gender was surely not accidental – women had been given the vote in the limited elections just three years earlier. Suddenly, they were allowed to drive. By 2023, the first Saudi female astronaut had visited outer space even as women’s subordinate status remained enshrined in law.

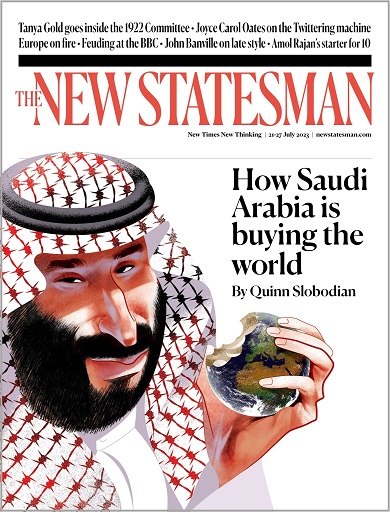

Like almost everything in Saudi Arabia in the past several years, the screening of Black Panther was the project of Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), then in his early thirties. He manoeuvred to the position of crown prince in 2017 and became the most high-profile statesman in the kingdom by launching Vision 2030, a long-term plan to develop the country’s public services and diversify its economy away from oil. In his first year as ruler he detained a group of high-net-worth individuals, including key members of the royal family, on charges of corruption in the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton. It is not too far-fetched to speculate that MBS saw himself in the role of the Black Panther T’Challa, guiding his kingdom with a firm hand on the tiller.

Aesthetically, Saudi Arabia’s crown prince seems to be leading the kingdom Wakanda-wards. Since the rise of MBS, it has been difficult to transcribe the press releases from Saudi ventures without feeling like you’re penning short stories of speculative fiction. This is no coincidence. A confessed fan of science fiction, MBS has commissioned experts in the fantastic to help design his new national projects.

One cultural studies scholar, Chris Hables Gray, worked with a team to help create an aesthetic typology of different subgenres, with “solarpunk” and “post-cyberpunk” leading the competition. But the Saudi scale is greater than fiction. Larry Niven’s and Jerry Pournelle’s dystopian sci-fi novel Oath of Fealty (1981) features a cubical city called Todos Santos or the Box, which surpasses the Los Angeles skyline. In 2023 Saudi Arabia announced a real-life project that is twice as big: an ornately decorated cube called New Murabba, with every side 100m longer than the Shard. The cube will contain a tower and close to twice as many square metres of office and shopping space as the whole of Canary Wharf.

Yet even this “giga-project” is only a sideshow to Neom, a half-trillion-dollar, 10,000-square-mile city planned for the south-western corner of the Saudi peninsula, which MBS announced a few months before the Black Panther premiere. The project is billed in a sun-dappled promotional video as “a start-up the size of a country”. The most complete version is currently on display at the Venice Biennale of Architecture. The exhibition is called “Zero Gravity Urbanism”, and features the first mock-ups by the “starchitects” for Neom’s centrepiece, the Line: two 500m-high skyscrapers facing each other over a city stretched in a line across 170km of desert.

Those involved in the construction of Neom include some of the biggest architect firms in the world, from Coop Himmelb(l)au (which designed the European Central Bank), Adjaye Associates (which designed the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture), and Morphosis. In the models, the Line’s outer walls are reflective solar panels charging the city within. The space between the two buildings is ravine-like and populated by the jutting polygons, right angles and blobs that have been the hallmark of avant garde architecture since Peter Cook and Archigram designed “plug-in cities” 60 years ago.

Cook’s office is itself designing one segment of the Line. The simulated fly-throughs of Cook’s design careen through a claustrophobic alley of modular apartments, with jutting balconies connected by skybridges and covered in hanging gardens – implying a staggering amount of water needed for irrigation. While the architect of Wakanda’s Golden City emphasised public transportation, the Line appears to be designed for the long-promised personal helicopter taxis, which recently had their first successful test flight in Riyadh.

It is hard to tell how much of the Saudi vision is real because so much depends on breakthrough technologies, and there are so few precedents for ventures at this scale. There is also the distortion effect created by a large payroll. So many consultants, design firms and architecture offices are getting paid that it serves their interest to play along. The Neom job page lists more than 300 open positions, from fish welfare manager to music teacher to financial data modeller, all presumably very well paid. The first rule of the gravy train is you don’t ask why the gravy keeps coming.

There is also the question of the bonesaw. As a person who has worked in the region for years told me, one of the reasons there isn’t that much journalism is the fear of being “iced out, or worse”. I am not the first to make a connection between Saudi Arabia and Wakanda. On Black Panther’s screening in 2018, a journalist and political operative named Jamal Khashoggi did too. In a column for the Washington Post, he speculated that the real vibranium was “stability, financial strength and strong foreign relations” and suggested the kingdom promote pluralism in the region.

“Will Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who likely will soon become king of his country, use his power to bring peace to the world around him?”, Khashoggi asked. Six months later, he discovered the price of asking such questions when he walked into the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, and was later carried out a dismembered corpse.

Norman Foster left the Neom project after Khashoggi’s murder, but many others stayed or have joined since. The death of one resident of the supposedly blank space on the map where Neom is to be built – Abdul Rahim al-Howeiti was shot by Saudi forces in April 2020 after he accused the country of “state terrorism” over his compulsory eviction – has not deterred the starchitects, nor has a recent statement of concern by UN rapporteurs of the likely execution of three more residents. It’s also been reported this month that a woman has been sentenced to 30 years in prison for criticising Neom on Twitter.

Gross violations of human rights have not halted the march of top-tier sports stars to the kingdom. The last year has seen what one observer called a “tsunami of soft power”. The most high-profile example is the multi-billion dollar merger of the Saudi golf league LIV with the PGA Tour, as the money offered was enough to overcome any reservations held by the sport’s executives.

Football has been another site of expansion with the Saudi acquisition of Newcastle United in 2021, and the Saudi Professional League now competes with China and the US as the place where footballers spend the final years of their careers. Cristiano Ronaldo, Karim Benzema and many others have recently moved to the Gulf.

Watching from the North Atlantic, it is tempting to alternately laugh and shudder at Saudi Arabia’s plans, and the craven motives of those willing to help realise them. But making sense of the kingdom is necessary because of its unusual status. Saudi Arabia maintains one of the few wells of money able to be drawn from during a time when ever higher interest rates have made reservoirs of capital evaporate into salt flats. As one AI expert eager to find backing put it bluntly, “the Saudis have the advantage of just having cash”.

In challenging times, Saudi Arabia has become a source of investment and a lodestar for both right-wing politicians and the broader corporate world. We might not like its plans but Saudi Arabia, ironically a country which owes its wealth to oil, may be one of the few countries with the means and drive to plan for a post-carbon future. If it becomes a thriving exemplar of capitalism without democracy, the prospect of a Saudi century has consequences for us all.

Illustration by André Carrilho

As with Black Panther, the story of Saudi Arabia in modern times must begin with a natural resource: oil. Like coal before it, the significance of oil is how it allowed us to break our dependence on direct energy from the sun. Instead, it fixed the heat in place. The environmental historian John McNeill calls coal “frozen sunshine”. It yielded half again as much energy per ton as firewood and three times as much as peat, another now-forgotten energy source.

We have only been in the age of oil for about five generations. It was around 1960 that global coal use was eclipsed by the “liquid sunshine” of oil, which produced twice as much energy as coal.

The move from a rock chipped from a wall deep underground to a fluid easily tapped from the surface was also an event in class politics. To harvest coal required the participation of communities that had the ability to bring the economy to its knees by stopping the lifts. Oil, by contrast, was easy to extract, store and most importantly, to transport. With the discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia in 1938, and the establishment of the Arabian-American Oil Company (Aramco), there was a new source of captive sunshine. Why negotiate with the labour unions in the north of England if you could deal with the sheikhs of the Gulf where labour unions were banned?

In 1960 Saudi Arabia formed the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) along with Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Venezuela, with other countries to follow. In 1973 the Arab members of the cartel used the “oil weapon” to protest against countries who had supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War, such as the US. The grievance was smoothed by what became a quadrupling of the oil price, supercharging revenues for the countries with the deepest reserves of liquid hydrocarbons. At the time, the kingdom’s crude oil reserves were estimated to be the largest in the world.

Being too reliant on a single commodity, no matter how plentiful or desirable, can be bad for a nation. What is commonly known as Dutch Disease means resource windfalls can produce inflation, enrich a small elite against the masses, siphon wealth out of the country, and make it unprofitable to build a domestic manufacturing base. The resource drug is too good to stop taking.

Focusing overwhelmingly on oil, Saudi Arabia recycled its receipts back into investments abroad and, most notably, American arms. While the famous deal made between US president Franklin D Roosevelt and King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud in 1945 exchanged access to Saudi oil for security, it was not meant to be provided gratis. Saudi Arabia has been one of the top customers for US arms exports for the past several decades, ranking in the top 20 worldwide for military expenditures.

While Saudi Arabia focused on oil and weapons, one of its smaller neighbours, paradoxically blessed by the lack of deep oil reserves, forged its own path. Beginning in the 1970s, the emirate of Dubai, a patch of land of just 35 square kilometres, began to present itself as an empty platform on which anything can be built, bought or bolted. In the metaphor of the late historian Mike Davis, the city created “legal-regulatory bubble domes” – multifarious zones with bespoke sets of laws designed to lure investors, whether it was into the International Financial District, Education Zone, Media City, or the headline-producing archipelagos of artificial islands in the shapes of palm trees and continents.

In the early 2000s, Dubai went global, creating miniature versions of itself around the world in a series of ports run by the state-owned logistics company DP World. The UK has been a special focus with DP World managing ports at Southampton and Thames Gateway and acquiring P&O Ferries, where in 2022 it sacked around 800 staff overnight.

Three developments have made Saudi Arabia take another look at the Dubai model in recent years and enter into a fierce competition with the emirate for the status of the region’s leading capitalist brand. The first is technological. The US success with fractional drilling meant that by 2019 it had gone from being a net importer to a net exporter of petroleum for the first time since 1949.

The second is geopolitical. The rising economic power of China, along with its deepening alienation from the US after Donald Trump’s initiation of a trade war in 2016, offered Saudi Arabia a chance to work between the camps. At the same time, the so-called Opec+ group added non-Opec countries, including, most importantly, Russia to counterbalance US power. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, Saudi Arabia and OPEC+ have occasionally acted to frustrate US efforts to shift global oil prices.

[See also: Saudi Arabia is the biggest beneficiary of the war in Ukraine]

The third is ecological. With the overwhelming evidence of climate change, Saudi Arabia senses that the terrain for a global investment and even patterns of urban development are changing in a fundamental way. They have no desire to ramp down fossil fuel production quickly – indeed, last year at Cop27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, the kingdom joined China in opposing language in the final text about phasing out all fossil fuels. But it wisely wants to avoid placing all its chips on the potentially stranded asset of petroleum.

When the hundreds of thousands of Saudis who went abroad to study on the King Abdullah scholarship programme from 2005 onwards returned, they brought back the same Obama-era spirit of enlightened capitalist technocracy shared by Rishi Sunak and Emmanuel Macron. Seen through the management consultant’s philosophy of governance, diversifying away from oil allows Saudi Arabia to expand its domestic economic base, and create more national self-sufficiency in a chaotic and potentially less carbon-dependent future.

Saudi’s emulation of the Dubai model is most obvious in the push for tourism and financial services. The Saudi budget airline Flynas has ordered 120 new planes from Airbus, a major expansion of its fleet. It also announced plans for a new carrier, Riyadh Air, to compete with Emirates and Qatar Airways, with discussion of ordering 150 aircraft from Boeing and more from Airbus. One of the Vision 2030 goals is to have Saudis stay and spend their money at home. By easing the process for acquiring a visa, it hopes to bring in more foreign tourists too.

Dramatic events – such as the Saudi bid to host a world fair called Expo 2030 – and the “sportswashing” around major competitions, such as the 2029 Asian Winter Games at Neom, are eye-catching. But the numbers involved in less glamorous industry are much larger.

The $2bn the kingdom spent on LIV Golf seems like less when you realise that in the last week of June alone – the annual week of the Hajj – the Saudi government signed contracts worth nine times this amount. South Korea’s Hyundai secured a $5bn contract with Aramco to build a petrochemicals plant. An Italian engineering group won a $2bn contract for another petrochemical expansion at a refinery. A third contract was agreed, for $11bn, with the French multinational Total-Energies for another petrochemicals facility.

Unlike Dubai, Saudi Arabia combines a focus on services and logistics with heavy manufacturing and “import substitution industrialisation” – decreasing its dependence on more developed countries. The world’s biggest steel maker, China’s Baosteel, announced plans to set up its first overseas steel plant in one of the kingdom’s newly created special economic zones. Saudi Arabia is a lead bidder to take 10 per cent in a Brazilian mining company that focuses on nickel and copper. It is also working with existing asset managers, signing an agreement in November with BlackRock to jointly invest in infrastructure projects.

Another signature project of Vision 2030 is a domestic electric vehicle (EV) industry. Saudi Arabia has a stake of more than $8bn in the EV company Lucid. Construction began in 2022 on a plant in Jeddah with projected production of 155,000 cars a year.

As a developing economy, Saudi Arabia is refusing the binary between domestic resilience and export-led growth. Instead, its approach is a mixture of old and new, building local industrial capacity while also continuing to lean into the advantage it enjoys in matters of oil and solar.

In the 19th century, David Ricardo’s famous example of “comparative advantage” was of Portugal focusing on wine because of its sun, while Britain focused on cloth. Few places have more sun than Saudi Arabia – but why not make cloth too, the Saudis wonder. By using the receipts of one approach to finance the other, Saudi Arabia can guard against a near future where exogenous shocks – from extreme weather patterns to democratic deadlock – make the existing world order brittle and prone to fracture.

The primary agent for this maelstrom of activity is the sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF). While PIF is in the top ten of global sovereign wealth funds, one of the goals for the Vision 2030 report was to increase PIF’s assets by more than ten times. It announced plans to transfer ownership of Aramco to the PIF to make it the “largest sovereign wealth fund in the world”. As of 2023, this has happened only in small drips – the 4 per cent of Aramco recently transferred to PIF is worth $80bn – but the logistical challenge of a full transfer is mind-boggling.

In 2021, PIF officially inaugurated a new tower, the tallest in Riyadh. At 80 storeys, its angular surface supposedly references the crystals found in the dry riverbeds of the Saudi desert. The pillar of metallic diamonds looks, it must be said, a lot like Wakanda.

Black Panther is a milestone in the cultural tradition of Afrofuturism. As such, it is shot through with Afro-centric politics. In one dramatic scene, a challenger to the throne enters the Museum of Great Britain and takes back a seventh-century war hammer by force. Much of what was exhilarating about the film was its inversion of the racialised power structures of the imperial and post-colonial world. Here, one of what WEB Dubois called “the darker nations” is on top.

Is there any way of seeing Saudi Arabia in a similar role? It would not be without precedent. The use of the oil weapon in the 1970s came attached to a Declaration of the New International Economic Order, which sought to undo colonial economic legacies and produce a more equitable community of nation states after empire. Saudi Arabia played a role in the Group of 77, a coalition of developing countries in the UN General Assembly. In a recent Foreign Affairs article, one analyst goes as far as to see Saudi Arabia resurrecting the 1970s dream of a “non-aligned movement”.

China has a central role to play here. Xi Jinping’s three-day visit to the kingdom in December 2022 produced a flurry of deals worth $30bn. At a more recent summit, a Chinese spokesperson expressed their willingness to help “de-Americanise” Saudi Arabia. The centrepiece of the conference was a $5.6bn deal with the Chinese EV company Human Horizons, which produces the luxury HiPhi brand. Saudi Arabia is also investing abroad, with billions in new and existing refineries in north-east China and South Korea.

At some level the idea of “de-Americanising” Saudi Arabia is a contradiction in terms. The country’s most valuable corporation by a great distance is Aramco, a portmanteau of “Arab-American Oil Company”. The rise of the kingdom – the only one in the world with the ruling family in its actual name – cannot be explained without American patronage.

Yet Saudi Arabia sent representatives to a “Friends of Brics” (the Brics comprise Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) meeting in June, and discussed joining a Brics investment bank. Also present was Iran, which, after seven years reopened its embassy in Riyadh the week after the meeting in South Africa. This was a symptom of cooling tensions in the region after Saudi Arabia finally wound down its calamitous intervention in Yemen, which had exacerbated what the UN calls “the world’s worst humanitarian crisis”.

The détente deal with Iran was brokered by China. A cynic would see the kingdom’s flirtation with China, Russia and the larger Brics group as a question of tactics more than Third-Worldist ideology.

But what to make of MBS’s science-fiction visions? Are Neom and the Murabba just a half-trillion-dollar version of the urban legend about the Saudi prince’s diamond-encrusted Mercedes Benz? The title of a Bloomberg piece in 2022 was “MBS’s $500bn desert dream just keeps getting weirder”. The Saudis have been here before. In 2005, the government announced a $30bn plan to build six cities from scratch. Only one was built – and even there, a population of 7,000 was a far cry from the two million projected by 2035.

The same cynic might note that the first feature of Neom slated to open is Sindalah island, “curated” by an Italian designer and featuring a golf course, three luxury hotels, a shopping complex and 86 berths for yachts up to 75m long. There is irony in targeting those with the biggest carbon footprint as the first part of a move to a “sustainable” future. In these new high-tech redoubts, far from dense, expanding cities, residents can continue their lifestyles unchanged.

But drive through the valleys of western Massachusetts, on the other side of the world. There, where former factories have been turned into condos, pottery studios, or simply left to crumble, one encounters a functioning factory of Saudi Arabia Basic Industries Corporation (Sabic). In 2002 Sabic bought up the Dutch petrochemicals company DSM, with factories in Belgium and Germany.

The importance of Saudi money is impossible to overstate in times of scarce capital. But comparing the numbers involved is almost sad. The Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni is pleading with the Saudis for investment in a $1bn fund for her country. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia is quietly getting things done in the UK. In 2007 Sabic bought the old Huntsman chemical plant in the north-east England and is expanding operations, and the British Conservative Party lauded the kingdom’s investment in a chemical plant in Teesside.

Sabic’s front-page adverts in the Financial Times picture soft-lit scenes of domesticity and sustainability, and are placed alongside the fallen world of Swiss watches and Bulgari jaguars. The company enjoys a positive reputation for competence and innovation.

Sabic’s Teesside factory recently threw a wholesome event with go-karting, caricaturists, and the chance to “sample a range of non-alcoholic drinks such as gin, lager, wine, cider and prosecco”. It is easy to see why the British government is happy to look the other way on Saudi Arabia’s human rights records and, as recently reported, is putting forward British partners for Neom. The Gulf is pulling off the heavy-handed combination of traditional morality with hyper-capitalism, which the Tories could only dream of achieving.

The kingdom has also made a push into “green hydrogen.” In May Saudi Arabia signed a deal to build a green hydrogen production facility with investment of $8.4bn, as well as an additional $6.7bn for the plant’s engineering, procurement and construction. The electrolysing process at the heart of green hydrogen is energy-intensive, but solar can fill this role. Solar trackers are being supplied by a Spanish provider, and the Indian multinational Larsen & Toubro is providing the solar, wind, and battery storage. As a pioneer in desalination, kingdom also has a jump on the seemingly insurmountable problem of water.

Squint hard enough and what critics justifiably call “Blade Runner in the Gulf” can look as much like the international energy utopias of Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future. Successful investments in renewable energy at scale would lead many to forgive the super-yachts.

If crypto technologies, such as doge coin and NFTs, were the morbid symptoms of the age of zero interest-rate policy, then an EV plant in the desert might be emblematic of an era where the smart money wants some industrial capacity and supply-chain resilience to go with its quick profits. It is an open question how many of the contracts signed will come to fruition but, as the narrative that Saudis tell themselves goes, even if a small fraction of the colossal effort is realised, it will be a major victory.

Another way to put this is that capital is learning some patience and Saudi Arabia is one place where the feeling is that, even if time is on nobody’s side, they are holding a better hand than most – or perhaps anybody.

In their 2018 book Climate Leviathan, the geographers Geoff Mann and Joel Wainwright describe a range of possible futures under the conditions of climate breakdown. One possible situation is “Climate Leviathan”, where countries opt into internationally, binding agreements, giving up some of their own autonomy for the sake of collective survival and coordinated action. Another is “Climate Behemoth”, where countries simply engage in their own zero-sum push for advantage in an unruly world.

Although Saudi Arabia pays the usual lip service to multilateral organisation, it seems best to see it as a Climate Behemoth. It requires none of the traditional forms of democratic legitimation. Even if infighting in the royal family is vicious, contenders for leadership are contained within a hereditary bloodline. The goodwill of the population is bought off in benefits and transfers for the roughly 60 per cent of the kingdom’s residents who are citizens. A persistent problem of what an expert in the region described to me as “hidden poverty” is one reason why the regime is expanding employment opportunities for citizens, part of the long-term timelines planned by the extravagantly well-endowed sovereign wealth fund.

After Trump’s election in 2016, to act like a Climate Behemoth looked like bad behaviour, a blip in what was described as the Liberal International Order, which had lasted from the end of the Second World War to the present. High-flown rhetoric and empty promises at international summits was still the dominant mode. But this is being rethought. Considering that no binding agreements were forthcoming and the world was only getting hotter, the oceans higher, and the ice caps dryer, maybe there was another way. Maybe an open and unabashed clash between sovereign states could perversely produce better outcomes for all. The former Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane wrote recently that “the global industrial arms race is just what we need”.

Until now, nothing has driven rich governments like the US to make the outlays of subsidies or investment needed to kick-start a just energy transition. What if a perceived geopolitical struggle of the US and its allies with China and Russia was the missing ingredient? Could it be that Saudi Arabia as a Climate Behemoth is leading the way? If so, the question is who would have the means to follow. MBS is not wrong to see the world historical status of his country. Others are beginning to see it too.

Vision 2030 begins with two solemn statements. The first is the recognition that “Allah the Almighty has bestowed on our lands a gift more precious than oil. Our Kingdom is the Land of the Two Holy Mosques, the most sacred sites on earth, and the direction of the Kaaba (Qibla) to which more than a billion Muslims turn at prayer.” The second pillar of the vision? “To become a global investment powerhouse.”

As for those with neither oil nor Allah, they can either watch dumbfounded or follow economic reasoning and turn to Mecca.

Quinn Slobodian is a New Statesman contributing writer and the author of Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy.

Source: The New Statement, 19 July 2023

How Saudi Arabia is buying the world – New Statesman

Comment here